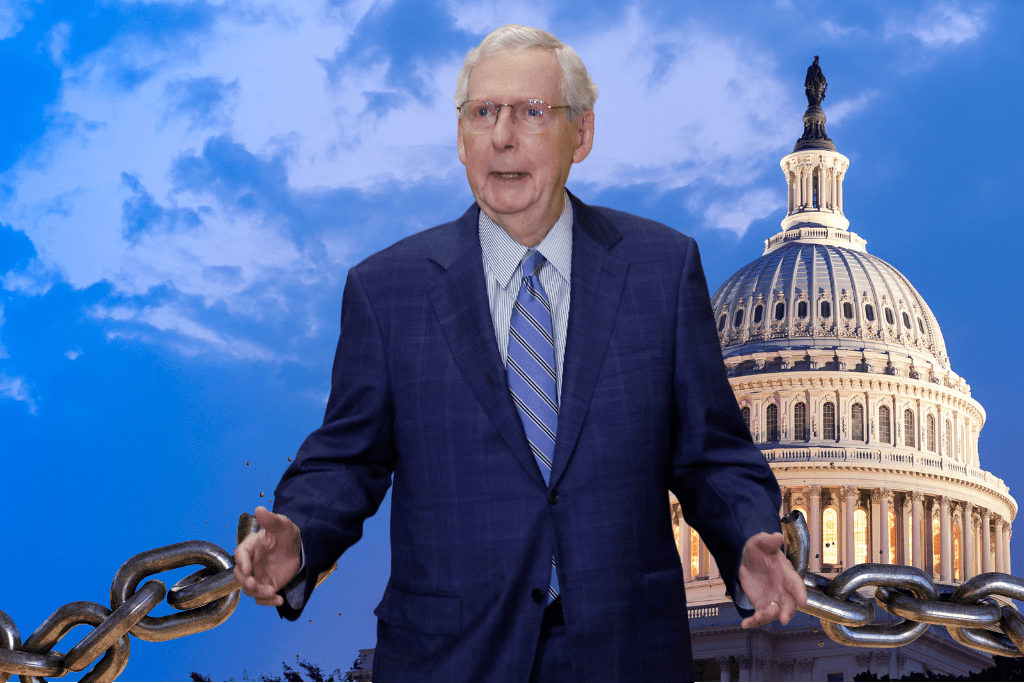

Mitch McConnell is the longest-serving Republican leader in the U.S. Senate, a titan on Capitol Hill, and a living legend in his home state of Kentucky in the mold of Henry Clay.

But in a speech in California last weekend, the 82-year-old senator was focused on his next, more mundane assignment: chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on Defense Appropriations. And he took clear aim at the isolationist foreign policy of the incoming president.

“With the party Ronald Reagan once led so capably, it is increasingly fashionable to suggest that the sort of global leadership he modeled is no longer America’s place,” McConnell said Saturday at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in Simi Valley. “But let’s be absolutely clear: America will not be made great again by those who are content to manage our decline. So how do we turn back this tide?”

It’s certainly odd that the most consequential Republican congressional leader in decades feels the need to “turn back” a trend within his party so at odds with his own foreign policy vision. Yet there’s no denying that Donald Trump’s brand of nationalism dominates the GOP and is remaking the party’s Senate conference, which has been much more immune from populist swells than the free-wheeling House of Representatives.

But if his recent moves and comments are any indication, McConnell is seeking to use what are likely his final two years in office—though with his advanced age and health issues, including a fall at the Capitol on Tuesday, even finishing his term is no guarantee—to take a stand for his belief that American might should be “rooted in the centrality of hard power and the importance of alliances and partnerships.” Given that he is stepping down as conference leader on January 3 and widely expected to retire from the Senate at the end of his term in two years, McConnell has the opportunity to take on one final, legacy-defining role: as one of the party’s last remaining Reaganites and a protector of the Senate as an institution against Trump’s designs to bend the Republican majority to his will.

(McConnell, of course, had an opportunity in 2021 to defend the integrity of the institutions of government and our political system: When Trump was on trial in the Senate after being impeached for his role in the January 6 riot. The Republican senator reportedly considered voting to convict the then-former president, but eventually opted against it while stating that the former president was “morally responsible” for what happened at the Capitol.)

Through his spokesman, McConnell declined to speak about his plans and thinking. But the Kentuckian has been dropping hints for weeks about how he’ll proceed as a relatively free agent.

“Defending the Senate as an institution and protecting the right to political speech in our elections remain among my longest-standing priorities,” McConnell said in a statement last month about becoming chairman of the Rules Committee, a powerful post from which he could provide a necessary bulwark against calls by Trump to get rid of the legislative filibuster, which McConnell said in November would be “very secure” if the Senate was in Republican hands. And a week after Election Day, accepting the Irving Kristol Award from the American Enterprise Institute, McConnell underscored his support for the check on the majority’s power just days after Republicans declared total victory in the presidential and congressional elections.

“It’s been quite evident to me that a credible check on majority rule was worth preserving even when it didn’t serve my party’s immediate political interests,” he said. “And why is that important? Because wild swings in policy with every transfer of power don’t serve the nation’s interest. For consequential legislation to endure, it should have to earn the support of a broad coalition.”

In the same November statement on his Rules Committee post, McConnell noted that the new Republican majority “has a responsibility to secure the future of U.S. leadership and primacy.” That presaged his more fulsome remarks in California last weekend about what American primacy in the world should look like, from a build-up of military capability to the U.S. “resisting neo-Soviet imperialism in Ukraine, Iran-backed terrorist slaughter in Israel, [and] PRC hegemony in the Indo-Pacific.”

In the near-term, McConnell is undeniably a swing vote on many of President-elect Trump’s controversial executive-branch nominees. The notoriously reticent senator has kept quiet about his views on Pete Hegseth (for defense secretary), Tulsi Gabbard (for director of national intelligence), Kash Patel (for FBI director), and Robert F. Kennedy Jr. (for health and human services secretary). Contrast that silence with McConnell’s statement after meeting Monday with Pam Bondi, Trump’s (backup) selection for attorney general.

“The American people deserve federal law enforcement authorities worthy of immense public trust,” McConnell said. “Ms. Bondi’s extensive legal and executive experience make her well-qualified to lead the Department of Justice.”

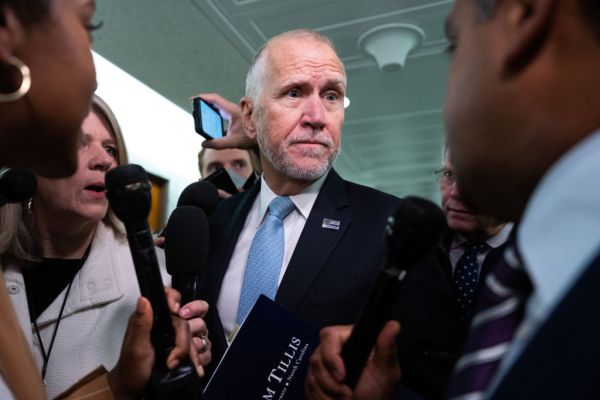

Such tea-leaf reading doesn’t guarantee he will ultimately oppose some or even any of Trump’s nominees, but the assumption in Washington is that McConnell remains a viable “no” vote. Lobbyists keeping a close watch on the nomination fights include McConnell along with moderate Republican Sens. Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, as well as wild card freshman Sen. John Curtis of Utah, on the list of those who could block Trump nominees. Given the division of power in the Senate and the fact that Vice President-elect J.D. Vance would cast a deciding tie vote, the power of those four swing GOP votes alone is undeniable.

McConnell’s position is certainly top of mind for many of Trump’s allies in the broader MAGA movement. Critics such as Steve Bannon have suggested that Matt Gaetz, Trump’s first pick to lead the Justice Department, withdrew from consideration due in large part to background machinations by McConnell. Gaetz himself has also blamed the aforementioned group of four for tanking his nomination, according to the New York Times.

The truth, however, is much closer to this: Opposition to Gaetz within the Republican conference appeared broad enough that the former Florida congressman quickly realized that he had no chance of success. Still, just a day after Gaetz withdrew, Bannon saw the hand of the outgoing Republican leader at work.

“The story is, Mitch McConnell is still controlling the deal,” he told The Dispatch.

What’s certainly the case is that McConnell is no longer bound by his obligations to the larger Republican conference or by fear of crossing the vindictive head of the party who despises him. (The feeling is mutual). Could he shirk that responsibility, as he did during the second impeachment, and defer to partisan loyalty? Or could Trump, and Washington, be in for a surprise as we head into McConnell’s final act?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.