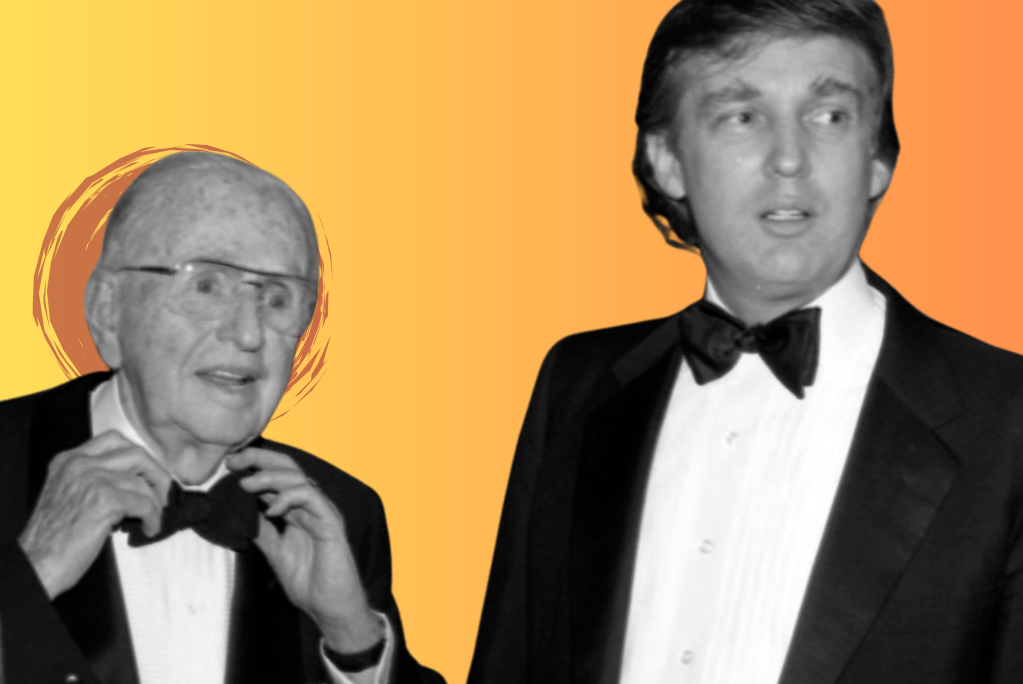

Happy Sunday. As our Dispatch Faith essay by writer Jake Meador points out today, Donald Trump’s connections to the late pastor Vincent Norman Peale are well documented. The author of the best-selling book, The Power of Positive Thinking, had an enormous influence on the incoming president.

But Peale’s approach is worth understanding beyond its influence on Trump, Meador writes, because it has pervaded whole swaths of American society and, as he argues, fooled many into believing a false version of Christianity.

Jake Meador: The Perils of Positive Thinking

In the classic Monty Python sketch “The Dirty Hungarian Phrasebook” John Cleese plays a Hungarian traveler trying, with the aid of an English-Hungarian phrasebook, to purchase cigarettes from an English tobacconist shop.

Unfortunately, the phrasebook is wildly inaccurate, leading to hilarious misunderstandings as Cleese, while attempting to purchase matches, says instead “my hovercraft is full of eels.” Cleese’s traveler is using the English language, but he has no idea what it actually means.

I thought of this sketch often as I read The Power of Positive Thinking, a bestselling book first published more than 70 years ago and written by Norman Vincent Peale, longtime pastor at Marble Collegiate Church in Manhattan and the former pastor to President-elect Donald Trump. Trump himself has praised Peale, saying to a group in Iowa that, “Norman Vincent Peale, was my pastor. … He was so great. And what he would do is, he’d bring real-life situations, modern-day situations, into the sermon.” Peale’s book was a publishing sensation from day one, has sold millions of copies, and launched Peale into a new level of fame and influence within American Christianity. Figures like Robert Schuller, Joel Osteen, and even in his own way controversial pastor Mark Driscoll are all downstream of Peale, whose emphasis on positive thinking and material success found an enthusiastic and rather eclectic audience.

Given his profession, it is no surprise that Peale’s book is replete with biblical quotations and encouragements to pray and read the Bible. But Peale’s use of Christian language and concepts is roughly identical to how Cleese’s character uses the English language: He can read it. He can enunciate it (for the most part). But somehow when he means to say, “I’d like to have some matches,” he instead says, “My hovercraft is full of eels.” All of Cleese’s gaffes result from the simple fact that he can (kind of) read and pronounce English, but he actually only speaks Hungarian.

But there is a great difference between being able to pronounce a language and being able to speak that language.

Just so with Peale: When he attempts to translate from the language he knows into the language he does not know, he is (like Cleese) entirely helpless. One could say Peale doesn’t really speak Christian; he merely reads it. He speaks something closer to “Western Educated Industrial Rich Democratic Individualist.” His Christianity is WEIRD, but not weird—and that is precisely the problem. Christianity, as its own Scriptures attest, is foolishness to the world. It speaks of a crucified God. It depicts poor people being welcomed into heaven while the rich languish in hell. Indeed, the mother of God herself praises the God who “exalts the humble” and sends the rich away empty. Christianity’s heroes are often unimpressive, sometimes even rather pathetic. But according to St. Paul, that is precisely the point: The wisdom of God is foolishness to the world. By this measure, Peale has firmly cast his lot with the world.

Ironically, for Peale the Christian message isn’t a message about the nature of reality, the reasons that mankind suffers and does evil, or the way that we might be saved from those things by something that exists outside of ourselves. It is not a story of God taking on flesh and entering the world as a rescuer, and the renewer of all things. Rather, Christianity—and really it’s just Christian words for Peale—is a technique for people in advanced industrial societies to achieve their dreams. It represents a kind of baptism of egocentrism for the wealthy and the powerful. Indeed, virtually every personal anecdote Peale shares involves well-to-do people. You will find many business owners, civic leaders, and men about town in The Power of Positive Thinking. What you won’t find are janitors or plumbers.

When Peale cites Scripture, it is invariably out of context and applied in ways that would have been quite shocking to the original authors. The point of one of Peale’s favorite texts—if God is for us, who can be against us?—is not that WEIRD people should pursue their personal kingdoms with confidence and positivity because God is on their side. It is, if anything, almost the opposite: The quite extensive witness of Scripture is that the sorts of people Peale constantly cites in his book are precisely the people least likely to enter the Kingdom of Heaven unless they repent of the very avarice and self-centered ambition that Peale’s work encourages.

The results of this confusion on Peale’s part in which he seeks to use Christian language to advance wealthy Western individualist goals are sometimes hilarious. In one passage, he explains that one can harness “prayer power” to achieve one’s goals, but only if one understands the rules and formulas required to pray “scientifically.” Thus:

An illustration of a scientific use of prayer is the experience of two famous industrialists, whose names would be known to many readers were I permitted to mention them, who had a conference about a business and technical matter. One might think that these men would approach such a problem on a purely technical basis, and they did that and more; they also prayed about it. But they did not get a successful result. Therefore they called a country preacher, an old friend of one of them, because, as they explained, the Bible prayer formula is, ‘Where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them.’ (Matthew 18:20) They also pointed to a further formula, namely, ‘If two of you shall agree on earth as touching any thing that they shall ask, it shall be done for them of my Father which is in Heaven.’ (Matthew 18:19)

Being schooled in scientific practice, they believe that in dealing with prayer as a phenomenon they should scrupulously follow the formulas outlined in the Bible which they described as the textbook of spiritual science. The proper method for employing a science is to use the accepted formulas outlined in the textbook of that science. They reasoned that if the Bible provides that two or three should be gathered together, perhaps the reason they were not succeeding was that they needed a third party.

And so the two industrialists invited the preacher to join them, they spent “several sessions” praying together, and then, Peale tells us, “they received the answer,” which was “entirely satisfactory.”

According to the wisdom of Scripture and mother church, prayer is a way of laying our fears and concerns before God. But it is not a self-help technique or a kind of celestial snack machine we visit whenever we are hungry. Prayer is a way through which human creatures enjoy communion with their creator and through which they are renewed and restored to what they were made to be. If you spend any length of time considering the way the Scriptures demonstrate prayer, you will quickly discover that prayer is often brutal and raw and even “negative.” The prayers of David are filled with angst and fear and despair. Peale, however, strongly discourages bringing any “negativity” into one’s prayers. Often prayers seem to go unanswered, not due to using the improper technique but, as the Scriptures tell us, because God’s ways are inscrutable to us, and the work of prayer is not so much to yield the results we want, but to align our fallen and imperfect will with God’s will so that we might be caught up in closer relationship with him.

All of this complexity, which one must speak Christian to understand, falls away in Peale’s work. It is almost as if he doesn’t even recognize such complexity as being part of the human experience, let alone the Christian experience. Prayer is simply a technique one practices in order to improve one’s daily material life, to help one’s mood, or, quite crassly, to grow one’s bank account. That Peale seems incapable of recognizing this is precisely the problem.

So why does this matter? Why bother with a book written more than 70 years ago by a man who died more than three decades ago? The most obvious answer is that tomorrow our nation’s next president will be sworn into office, a president whose ties to Peale and admiration of him are well documented. That is one reason: If we want to understand President-elect Trump’s relationship to Christian faith, we would do well to attend to the writings of the pastor who Trump has praised on many occasions—for the Christianity Trump praises is not historic orthodoxy, but rather the revisionist egocentric version articulated so clearly in Peale’s book.

But it would be a mistake to treat Peale only as a kind of cypher for understanding Donald Trump’s relationship to Christianity. The appeal of this Manhattan pastor transcends political divides because its appeal is founded on, as theologian Reinhold Niebuhr said back at the time this book was published, in “egocentricity.” And egocentricity is a vice not limited to Republican politicians. Indeed, on a past trip to Manhattan I walked by Peale’s old church—the one Trump attended as a child. What I found outside the doors of the empty church was a statue of Peale wrapped in a rainbow scarf. Egocentricity is a philosophy for all political ideologies, it turns out.

Indeed, what came to mind more and more as I read Peale is that his is a kind of prototype for what the sociologist Robert Bellah described as “Sheilaism” in his 1985 book Habits of the Heart. “Sheilaism” is so named because of a particularly stark quotation from one of the subjects of Bellah’s work, whom he referred to as “Sheila Larson.” This is how “Sheila” described her religiosity:

I believe in God. I’m not a religious fanatic. I can’t remember the last time I went to church. My faith has carried me a long way. It’s Sheilaism. Just my own little voice … It’s just try to love yourself and be gentle with yourself. You know, I guess, take care of each other. I think He would want us to take care of each other.

Peale is more assertive about church attendance than Sheila is, but only because for Peale church attendance is a good tool to promote one’s own well-being and get what one desires, because at church one can find other people marked by the same positivity and self-belief that Peale commends. Indeed, this is perhaps a telling example of where Peale’s philosophy has led over time, for such an egocentric account of Christianity is extractive and corrosive when given time to work. From Peale’s time to Bellah’s, the reason for church—worship of a being outside of ourselves—fell away. More recently, the same self-aggrandizement has banished civic society and public virtue altogether—with perhaps the clearest picture of that dissolution being Trump himself.

In a telling anecdote shared in a recent Atlantic feature, editor Jeffrey Goldberg recounts a story from Trump’s former chief of staff John Kelly of a time when he and Trump visited the grave of Kelly’s son, who was killed while serving in the U.S. armed forces:

Trump, while standing by Robert Kelly’s grave, turned to his father and said, “I don’t get it. What was in it for them?” At first, Kelly believed that Trump was making a reference to the selflessness of America’s all-volunteer force. But later he came to realize that Trump simply does not understand nontransactional life choices. I quoted one of Kelly’s friends, a fellow retired four-star general, who said of Trump, “He can’t fathom the idea of doing something for someone other than himself. He just thinks that anyone who does anything when there’s no direct personal gain to be had is a sucker.” At moments when Kelly was feeling particularly frustrated by Trump, he would leave the White House and cross the Potomac to visit his son’s grave, in part to remind himself about the nature of full-measure sacrifice.

It is one thing to embrace Peale’s egocentric WEIRD pragmatism in a society that still has robust norms of civic life along with many altruistic people engaged in public life whose lives are a repudiation of egocentric pragmatism. It is another thing to embrace that same ideology in a country consisting almost entirely of other people who have embraced the same, which is where we now find ourselves. Peale’s positive thinking has loosed millions—Trump not least of all—to achieve their dreams through uncritically assuming that God’s only desire for them is that they would be happy and fulfill their own desires.

The irony in all this, of course, is that when C.S. Lewis imagines hell in The Great Divorce, that is precisely what it looks like: isolated and scattered individuals looking out for themselves. But, of course, why would anyone listen to C.S. Lewis? His hovercraft was full of eels, you know.

Nicole Penn: American Heretics and Heroes

For the website on Saturday, scholar Nicole Penn reviewed Jerome Copulsky’s new book American Heretics, on religious thinkers who criticized the Founders for seeking to limit the government’s involvement in religion.

Although Copulsky focuses primarily on Christian thinkers, his study shows how they levelled a wide range of assaults on some of the foundations of American governance codified in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. He convincingly portrays these figures as snakes in the American garden. In doing so, however, he misses an opportunity to interrogate the photonegative image of the United States that their critiques reveal. These men may be heretics, but the American orthodoxy they are dissenting from is not limited to the staid principles of our founding documents.

A key commonality among American Heretics’s subjects is the belief that the Revolutionary generation committed a founding sin in refusing to use the weight of the federal government for religious ends. Eighteenth-century Anglican loyalists and 19th-century Catholic traditionalists both balked at the American rejection of a government entwined with a state religion. Presbyterian Covenanters and Protestant Reconstructionists waged lengthy political and intellectual campaigns to rededicate American governing institutions to Christianity. And a cadre of contemporary postliberals have lobbed viral invectives against the decadence engendered by American religious pluralism.

The Dispatch Faith Podcast

Last week, former State Department envoy Knox Thames wrote an essay offering practical ideas for the incoming Trump administration to ensure religious minorities are protected in Syria following last month’s regime change. This week, he joined me on the Dispatch Faith podcast to talk about that, his experience working in multiple presidential administrations, and the problem posed by global religious persecution. These weekly conversations with Dispatch Faith contributors are available on our members-only podcast feed, The Skiff.

More Sunday Reads

For Mosaic, American academic William F.S. Miles recently visited a Druze village in the Golan Heights—or the “occupied Golan Heights,” as his host Walid (a pseudonym) insisted—to understand how the adherents to the offshoot of Islam manage an identity shaped both by a sense of homelessness and the civilizations all around them. “For Walid, there is a concerted effort by Israeli education authorities to separate Druze from Arab identity. He cites the imposition of Israeli ID cards in the early 80s, which gave rise to strikes and stone throwing,” Miles writes, then goes on to quote Walid: “I had a classmate whose father was very politically involved. Once, in class, he asked the moreshet (culture) teacher: ‘Why is it that we learn about Jewish history and culture, and about Druze history and culture, but we don’t learn about Arab history and culture?’ The teacher had no answer. What could he say? Only, ‘This is what the Ministry of Education has decided, and I have to follow it.’” Walid, Miles notes, “is also squeezed. Squeezed between a Syrian nationalism he cannot kick and a Zionist reality he cannot resist. Squeezed between an Arabic that he cultivates in his children and a Hebrew that is a ticket to their opportunity. Squeezed between a Lebanese terrorist organization and a Jewish state which will defend him, and his land, as its own.”

A Good Word

I’m admittedly late to this, but it’s well worth a few minutes of your time. In a guest post for Jonathan Haidt’s After Babel Substack earlier this month, Christian writer Andy Crouch addresses “magic”—what he defines as the “instant, effortless power” that technology increasingly seeks to provide—and cautions us not to employ it at the expense of personal formation, especially for young people. “And there is one last benefit of giving [magic] up, at least in our formative stages and places,” Crouch writes. “If there are two kinds of magicians in the Western imagination, Faust who clings to magic and Prospero who renounces it, there are also two kinds of magic. One, the magic of the alchemists, is the quest for domination and control of nature and whatever powers may lie beyond nature. But there is another magic, best captured by the idea of the enchanting—the sense, often unbidden and seen only out of the corner of our eye, that something wonderful, awesome, majestic, and mysterious is afoot in this world, something for which control is simply not the right word, indeed something which we would not want to control for fear of diminishing its beauty and its goodness. If the quest for the first kind of magic drives a prideful quest for power, the second kind of magic produces in us something much closer to humility. For almost ten years now, I have started my day by going outside, well before I look at any screen. In the morning quiet, and this time of year the morning dark as well, the stars may be bright, or the sky may be the darkest of grays, with clouds low overhead. Some mornings it is raining, on a few mornings snow is falling. Whatever the weather, I stand out there, usually longer than I planned, feeling … small. I am just a creature, I think, as I take a few slow breaths. I am part of something so much larger than myself. And most mornings, I find gratitude and prayer rising up almost involuntarily. Out here, I am no magician, but I am in the presence of a deeper and truer magic than the alchemists dreamed of. Back inside the house, the screens await me, and when they start glowing they will tempt me to enlarge myself and shrink my world to that very small part which I can control and master. But for a few crucial moments, real life seems worth the wait, worth the effort. It is worth it to not settle for anything less than the personal.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.