The first thing to know about the Department of Government Efficiency is that it doesn’t exist.

“DOGE” is just a dumb reverse-engineered acronym (a reference joke for the crypto-bros) for the vanity-hobby project that will be overseen by Elon Musk until he gets bored by it. Creating an actual government department takes an act of Congress, which has not happened and almost certainly will not, because the incoming administration and its friends want to use DOGE and other informal arrangements to evade laws and regulations pertaining to official federal acts or to a “federal advisory committee”—you know, little things like conflict-of-interest rules, transparency, recordkeeping, etc. (For more on the legal aspect, listen to Advisory Opinions on the subject.)

DOGE’s lack of legal status may help it to elude oversight, at least for a while, but it also means that DOGE has no real power. Musk may think that his currently cozy relationship with Donald Trump gives him some clout, but many other men of his sort have suffered from that delusion before him, and they all found out the hard way that there is no point in trying to be the best friend of a man who has no friends at all.

Ask Steve Bannon about that.

Beyond the legal problem—and the political problem, which we’ll get to soon enough—DOGE has a math problem. Musk says he wants to cut $2 trillion from the federal budget. Of course, he’s already backpedaling away from that—he’s doing the Trumpy thing of insisting that his unrealistic, ignorant bulls—t is part of a negotiating strategy—and now says that his $2 trillion target is really a way to get to $1 trillion in cuts. So, let’s take that as the $1 trillion challenge.

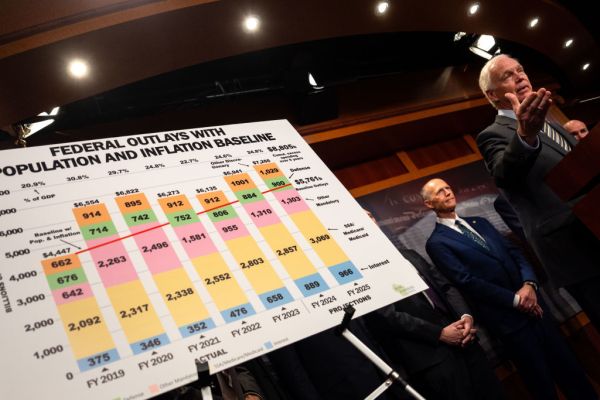

Donald Trump has said, many times, that cuts to entitlements are off the table. He has, at times, talked about cutting defense spending, and Musk et al. are very interested in the Department of Defense’s sloppy audits (oh, but here’s cable-news clown Pete Hegseth to sort out the financials!), but history and political reality suggest that defense cuts are not going to be forthcoming, either. For one thing, Trump doesn’t like doing hard or unpopular things; recall that he is the guy who wanted to put his own name on those COVID-relief checks. For another thing, congressional Republicans do not want to cut the defense budget—in the main, they want to increase it. And for a third thing, there is the matter of his own track record: Trump talked about defense cuts the last time around, too, and then signed the biggest defense budget in American history and, of course, boasted about it.

Some context: That biggest-ever defense budget was indeed the biggest ever in nominal-dollar terms, but in GDP terms—the more relevant measure—it was a relatively small budget by historical standards. In 2021, the United States spent about 3.4 percent of GDP on defense, half of what it spent in 1982. If you believe that we are, indeed, in a new cold war, one in which the People’s so-called Republic of China plays the role of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, then you probably should be thinking about how it is we are going to prevail in that conflict with relatively low spending to counter an enemy that is, unlike the USSR was, a major player in the world economy. In both nominal-dollar and GDP terms, defense spending went up a bit the last time Trump was in office, from 3.3 percent of GDP in 2017 to 3.4 percent of GDP in 2021 (it was 3.7 percent of GDP in 2020). I wouldn’t bet big on big defense cuts—or on meaningful defense cuts at all.

If entitlements and defense are quarantined, then that leaves our old friend, non-defense discretionary spending (NDD). Elon Musk is a pretty smart guy by most accounts, but he’s going to have a hard time getting $1 trillion in savings out of NDD, much less $2 trillion, because—see if you can follow the math here—NDD already is less than $1 trillion. NDD came in at just more than $917 billion in 2023. You could cut every nickel of it—all of the money the federal government spends on education, scientific research, highways, national parks, law enforcement, non-entitlement welfare programs, and basic operations such as running the courts and collecting the taxes and keeping the lights on in federal offices, and a million other things—without eliminating $1 trillion.

There’s no clever way around it: You cannot cut $1 trillion—much less $2 trillion—without putting either defense or entitlements (or both) on the chopping block.

Another way of saying this is that the budget balancers, be they at DOGE or in Congress—you know, the branch of government that actually has responsibility for taxing and spending and power over both—do not have a fiscal problem first and foremost: They have a political problem. Even if we forget about actually balancing the budget and embrace the more modest measure of successful fiscal reform—i.e., reducing the size of the annual deficit as a share of GDP consistently until GDP is growing faster than the national debt is—it is not going to happen until somebody shows the moral leadership and political skill to convince the American electorate that meaningful fiscal reform is going to entail real cuts in popular programs and, almost certainly—Republicans will want to cover their delicate little ears here and avert their eyes—higher taxes, particularly on the middle class, whose members currently pay approximately squat in federal income tax.

Our progressive friends do go on and on about the supposedly hyper-capitalist character of the United States and the scrooginess of its government spending compared to more enlightened countries. But that isn’t really true, as you can see for yourself in the IMF data. Switzerland runs a perfectly pleasant modern European welfare state with government spending that is significantly lower as a share of GDP than in the United States (31.5 percent for the Swiss vs. 36.3 percent for the United States). In fact, all-in government spending in these United States (federal, state, and local) is within spitting distance of the figure in Norway (38.5 percent), Australia (38 percent), or Canada (41 percent), and more than China (33.4 percent) or Russia (3 percent). The next time one of your progressive friends points to the high statutory tax rates of the Eisenhower era as a sign of a golden age, tell them to take a gander at all-in government spending in, say, 1957, when it was just over 16 percent of GDP, less than half of what it is today. (Taxes as a share of GDP were lower in the Eisenhower years than they have been recently, too—those high statutory rates applied only very narrowly.) This isn’t Singapore, where government spends only about a dime of every dollar of GDP—and, by the way, is life in Singapore really so bad in purely material terms?

Of course, we have to make allowances for cultural realities: Singapore is full of Singaporeans, Switzerland is full of Swiss people, Norway is full of Norwegians, and the United States of America is full of … people who will later today inaugurate a corrupt, makeup-laminated game-show host as their president. And it isn’t just a culture of egalitarian solidarity that has the Swedes, for example, relatively satisfied with their high-tax, high-spending government—Lars the Swede really does get more for his 11 Swedish krona than Joe American gets for his notionally equivalent $1.

We have a supposed Department of Government Efficiency that is going to be looking for spending cuts everywhere but where the money is. But there are other kinds of efficiencies, too: For example, the federal government fails to collect nearly $700 billion in taxes owed each year—seven-tenths of that $1 trillion target—but Republicans would rather ritually disembowel themselves than lift a pinky to address that. In fact, they cut another $20 billion out of the Internal Revenue Service’s budget in that end-of-year package cobbled together by House Speaker Mike Johnson. The IRS has its troubles, to be sure, about which I have written a great deal—but if we are going to have taxes, then we are going to have a tax-collecting agency. If Republicans wanted to replace the IRS with something more effective—or replace the income tax with a less destructive tax regime—that would be great, and I’d welcome the reform. But simply hobbling the tax agency we have isn’t going to make it any more honest or effective—if anything, it is likely to have the opposite effect.

I can hear you now: “But isn’t it worth looking for some savings somewhere?” Of course it is. How many blue-ribbon panels have we had on that over the years? And what do we have a Congress for, exactly?

And Furthermore …

“Human kind cannot bear very much reality,” T. S. Eliot wrote. He was talking about bigger things than the federal budget and more important things than who is elected president of the U.S. government. (Eliot, a son of St. Louis, did his very best to forget that he ever had been an American. One sympathizes. Living in the United States in our time is a little like being a crazy person with unwanted voices in his head, and I always find it a relief to be in a place where the language on the street is not English. Eliot ended up speaking an English that was more British than John Gielgud’s, and it was almost as good as a foreign language.) But we—we Americans I mean—cannot bear very much reality in the little things, either.

Sometimes, my very sweet-tempered 2-year-old son will ask for something we don’t have, such as an orange. And it goes like this:

“May I have orange, please?”

“I’m sorry, we don’t have any oranges right now. I’ll get some next time we go to the store.”

“But I will have orange … ANYWAY!”

I do love that my son apparently believes that I am omnipotent, at least when it comes to snacks, but with great power comes great responsibility. (Incidentally: Yes, he does say “may I” and “please” and “thank you,” though he does not yet have a handle on “a,” “an,” and the articles at large. He is polite when he is thinking about it, walks departing guests to the door and that sort of thing, but he will sometimes cry volcanically when denied something he wants or when something is taken away, and he will theatrically stamp his feet in frustration—which is something I had thought children did only in cartoons.) I don’t want him to figure out how little power I actually have—not yet, anyway, and not out of vanity, but because I want his world to feel like a safer place for as long as possible. He sleeps with a stuffed rabbit and recently said that his career goal is to grow up to be Santa Claus because Santa gives people presents and there is nothing so good as that, and I’m going to miss all that when it’s gone. I don’t want to go off on a whole parenting tangent here, but I don’t think little boys actually need “toughening up” the way we sometimes talk about it—the world already is sufficiently cruel, and I think that fathers who are mean with their sons for supposedly didactic reasons usually end up making weaker men rather than stronger ones.

Related to that, I detect some critical absences at work in our politics. Men who never got what they needed to get from their fathers don’t stop needing it or looking for it, but they go looking elsewhere, naturally in the wrong places and often in destructive—especially self-destructive—places. Men who never got from God what they needed don’t stop looking for it, either, and that, too, leads to destruction in many cases. Church, family, community—men never stop needing things and never stop looking. We are hunters and gatherers, and not only of wooly mammoths and berries. One need not reduce Christianity or any other religion to a mere psychological mechanism to appreciate that there are good reasons the world has only a few archetypes of the Almighty: father, mother. “Mother is the name for God in the lips and hearts of little children,” as William Makepeace Thackeray tells us. (And what a lovely Puritan name “Makepeace” is.) But what kind of a god?

Sometimes—once or twice in a week—that lady visited the upper regions in which the child lived. She came like a vivified figure out of the Magasin des Modes—blandly smiling in the most beautiful new clothes and little gloves and boots. Wonderful scarfs, laces, and jewels glittered about her. She had always a new bonnet on, and flowers bloomed perpetually in it, or else magnificent curling ostrich feathers, soft and snowy as camellias. She nodded twice or thrice patronizingly to the little boy, who looked up from his dinner or from the pictures of soldiers he was painting. When she left the room, an odour of rose, or some other magical fragrance, lingered about the nursery. She was an unearthly being in his eyes, superior to his father—to all the world: to be worshipped and admired at a distance. To drive with that lady in the carriage was an awful rite: he sat up in the back seat and did not dare to speak: he gazed with all his eyes at the beautifully dressed Princess opposite to him. Gentlemen on splendid prancing horses came up and smiled and talked with her. How her eyes beamed upon all of them! Her hand used to quiver and wave gracefully as they passed. When he went out with her he had his new red dress on. His old brown holland was good enough when he stayed at home. Sometimes, when she was away, and Dolly his maid was making his bed, he came into his mother’s room. It was as the abode of a fairy to him—a mystic chamber of splendour and delights. There in the wardrobe hung those wonderful robes—pink and blue and many-tinted. There was the jewel-case, silver-clasped, and the wondrous bronze hand on the dressing-table, glistening all over with a hundred rings. There was the cheval-glass, that miracle of art, in which he could just see his own wondering head and the reflection of Dolly (queerly distorted, and as if up in the ceiling), plumping and patting the pillows of the bed. Oh, thou poor lonely little benighted boy! Mother is the name for God in the lips and hearts of little children; and here was one who was worshipping a stone!

Now Rawdon Crawley, rascal as the Colonel was, had certain manly tendencies of affection in his heart and could love a child and a woman still. For Rawdon minor he had a great secret tenderness then, which did not escape Rebecca, though she did not talk about it to her husband. It did not annoy her: she was too good-natured. It only increased her scorn for him. He felt somehow ashamed of this paternal softness and hid it from his wife—only indulging in it when alone with the boy.

As a portrait of an unhappy marriage—or several of them—Vanity Fair offers all the darkness of three or four Thomas Hardy novels with half the effort and (at least) twice the humor.

A line from the novel was repeated as a theme for the (very good) 2018 television adaptation: “Everybody is striving for what is not worth the having!” I wonder what, if anything, those words would mean to such a man as J.D. Vance, who today will put his signature in blood on the contract outlining the terms of the sale of his soul—for cheap, too. What a mess of pottage he has got himself into. One might feel pity or contempt for a sycophant such as Sean Hannity or such a creature as Steve Bannon, but one cannot exactly be disappointed by them in the way one is disappointed by a man who has the capacity to want something finer and higher. You don’t blame a chimpanzee for being a chimpanzee, but you do blame a man for being one. Strange as it is, there are those among us who aspire to chimpdom, for whom chimpdom is a creed and a philosophy of a sort. I’m not in the self-help business, but here’s a little free advice: Try being human. It is a lot more work than accepting chimpdom, which comes naturally, but it will be worth it.

Or so I hear.

Words About Words

Time for another round of “That Stat Doesn’t Say What You Seem to Think It Does.”

From a press release:

Did you know one in five people without a college degree out-earn the median college graduate?

A new report from two national nonprofits, American Student Assistance (ASA) and Burning Glass Institute (BGI), reveals how certain non-degree jobs are significantly better for launching a young person into a higher earning job with more long-term potential than others.

These guys have their hearts in the right place, I suppose, and I am all for encouraging people who are not interested in a university education or college-level professional training to develop the skills and relationships that will lead them to satisfying and well-paid work. But what that number actually says is this: 80 percent of those without a college degree—a large majority—earn less than the median college graduate. On its face, that’s a pretty good argument for going to college, no? There are all sorts of arrows-of-causality-in-this-vector issues going unaddressed there (the sort of people who finish college degrees are also the sort of people who are likely to be relatively active and conscientious when it comes to job-hunting, etc.) (wrote the non-graduate) but, if that’s the stat you’re hanging your hat on, this isn’t the press release you write.

Economics for English Majors

If you’re not already econned-out, here’s an interesting bit from the deVere Group:

Rachel Reeves’ Budget last October has unleashed an unprecedented response, with 42% of those with financial assets in or ties to the UK actively now seeking to transfer their wealth and assets out of Britain and into more tax-friendly jurisdictions, according to a new survey.

This comprehensive survey by independent financial advisory and fintech deVere Group, conducted the week before Christmas among 600 individuals worldwide, underscores the widespread concern over the sweeping fiscal measures announced in Labour’s first Budget.

The survey’s findings reveal a seismic shift in attitudes toward the UK’s financial environment.

Families, business owners, and investors with UK financial connections are exploring options to mitigate the impact of the new tax landscape, which includes higher capital gains and inheritance tax changes on pensions, the abolition of non-domiciled tax status, and increases in National Insurance Contributions (NIC).

“These measures, designed to address fiscal challenges, are perceived as a direct threat to wealth preservation and financial planning. The policies outlined in the Budget are a game-changer for anyone with financial ties to the UK,” said Nigel Green, CEO of deVere Group.

“The poll shows a remarkable increase in the number of individuals seeking to reposition their wealth abroad. This is not a knee-jerk reaction — it’s a strategic response to an environment that has become increasingly hostile to wealth and investment.”

It is possible these findings are overstated. It also is possible that people respond to incentives and that rich people have more ability to respond quickly and decisively.

Which Reminds Me …

I filled in for Jamie Weinstein on The Dispatch Podcast today and had a very fun chat with Grover Norquist. Grover is someone I have a lot of disagreements with (I think we should focus on spending rather than taxes and have long been convinced that self-financing tax cuts are a delusion in most circumstances) but always enjoy talking to.

Grover Norquist is, in some ways, the model political activist: He has one issue, really, and he’ll work with anybody—Republicans, Democrats, libertarians, vegans, emu ranchers, yoga enthusiasts, the devil himself, even Republicans—who is willing to move his goals forward a few yards. And he is willing to tell his friends and allies in the Trump administration things they need to hear, i.e., that tariffs are taxes on American consumers and businesses.

Another way of saying that is that Norquist does what the National Rifle Association used to do: Focus on one important thing and keep hammering on it. And that’s a good way to go about doing it—even when he’s wrong.

MAGAbytes

Do read this: Very interesting discussion between Ross Douthat of the New York Times and venture-capital poobah/guy who kinda may as well have invented the web Marc Andreessen.

And Furtherermore …

There’s a line missing from the bio of one of our new contributors: Geoff Henley is, among his other sins, my old college-newspaper boss.

Elsewhere …

You can buy my most recent book, Big White Ghetto, here.

You can buy my other books here.

You can see my New York Post columns here.

Please subscribe to The Dispatch if you haven’t.

You can check out “How the World Works,” a series of interviews on work I’m doing for the Competitive Enterprise Institute, here. I think you’ll particularly enjoy my recent conversation with Magatte Wade, “Senegalese entrepreneur and one of the world’s leading African prosperity activists.”

In Conclusion

Guys, I said a “cold day in hell.” “Cold day in Washington” is pretty close, to be sure, but you’re going to have to do better. No sale.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.