On his first day back in the Oval Office, President Donald Trump wasted no time in reviving one of his most controversial foreign policy stances: initiating the withdrawal of the United States from the World Health Organization (WHO). The executive order he signed cites the WHO’s flawed COVID-19 response, its failure to reform, its alleged political biases, and disproportionate demands on American taxpayers. The directive also pauses U.S. funding, calls for U.S. personnel to pull out of WHO programs, and proposes forming new partnerships to replace the WHO’s work.

While the WHO’s glaring failures warrant serious scrutiny, withdrawing the United States outright may do more harm than good, unless the administration undertakes a much-needed overhaul of global health governance. The withdrawal would take effect in January 2026, and Trump has hinted that the U.S. could remain in or rejoin the health agency if reforms are undertaken. The WHO has lost its way in recent decades. Originally formed in 1948 to battle scourges like smallpox and cholera, the organization initially delivered major successes in outbreak containment and disease eradication. Over time, however, it has shifted its ambitions beyond infectious diseases, seeking more funding through special programs that appeal to wealthy donors—such as initiatives around climate change, to fight obesity, and to study the radiation risks of cellphones, to name a few.

This approach drew billions in voluntary contributions, with the money often earmarked for donors’ pet projects. Today, more than 85 percent of the WHO’s budget comes from these voluntary sources. The Gates Foundation has become the second-largest single donor after the United States and as such wields outsized influence, exemplifying how private and multilateral funding may skew the WHO’s agenda away from its core mission. The WHO often finds itself working outside its areas of competence, and some initiatives are counterproductive to the core mission. Working to limit fossil fuel use in emerging nations, for example, stunts the development that leads to better health and living conditions.

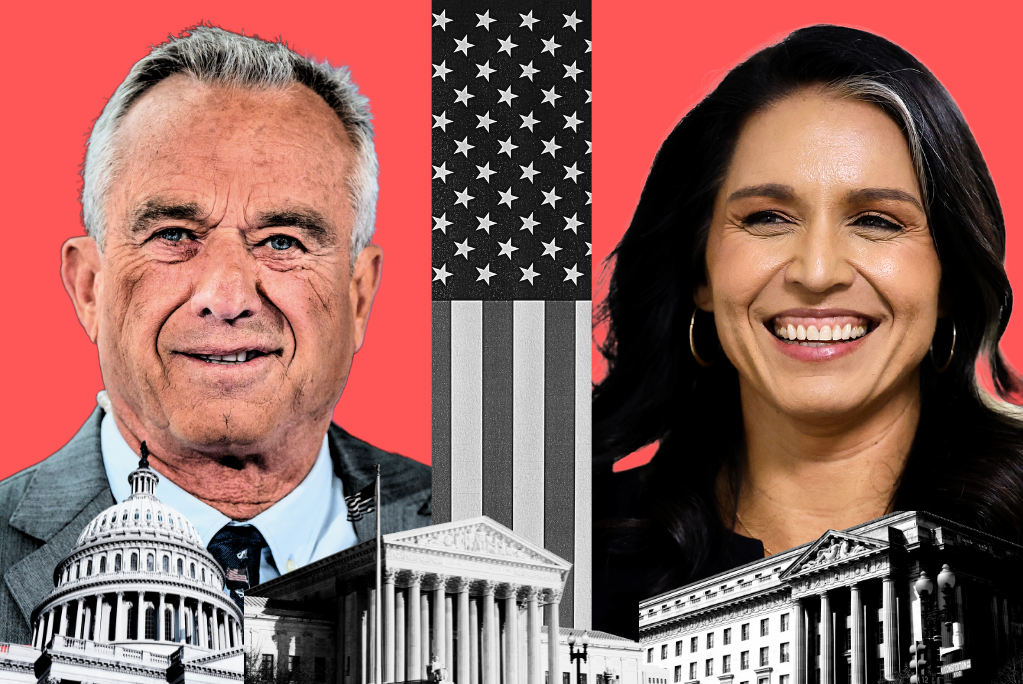

Roger Bate“Leaving the WHO might look like tough talk, but it risks sacrificing the chance to enact meaningful reforms or to shield Americans from future health crises. A more sensible approach is to use American influence to push for decisive changes in Geneva, including new leadership.”

Danielle Pletka and Brett D. Schaefer“The WHO has been a troubled organization for too long—troubles that were only highlighted by the pandemic. The U.S. will not cease supporting international health under Trump. But those efforts need not involve the WHO. The threat of withdrawal should be a wake up jolt to the WHO and its more responsible members.”

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the WHO’s shortcomings. The organization promoted heavy-handed lockdowns that proved socially and economically devastating, especially in poorer regions of the world. It also botched its investigation into the virus’s origins—initially deferring to Chinese authorities and delaying independent inquiries into whether the virus leaked from a laboratory in Wuhan. These failures have fueled the argument that the WHO is too politicized, too large, and too beholden to certain member states to respond effectively to global health crises.

But the path of withdrawal is fraught with danger. Even if one grants all of President Trump’s concerns, leaving the WHO outright would mean losing a seat at the table where key pandemic policies—like the proposed WHO Pandemic Treaty, which is still being negotiated—are shaped. If a new treaty moves forward without U.S. input, Washington would effectively surrender any direct influence over how a future pandemic is managed to the 193 other countries that remain in the organization. And to work with those countries, we might find ourselves forced to comply with WHO policies we had no role in shaping—on vaccinations, data reporting, and other issues. The United States might also find itself cut off from critical information-sharing, slowing its response to the next pandemic.

In financial terms, Washington represents roughly 16 percent of the WHO’s total funding. Losing those resources would be enough to sting, but not enough to “kill” the organization. China or other private donors like the Gates Foundation might well increase their funding, which could further shift the WHO’s priorities away from U.S. interests. Ironically, that might exacerbate precisely the issues President Trump cites when justifying American withdrawal.

Opposing Debate

A better solution would be to demand tangible reforms within the WHO while retaining leverage as its biggest state donor. The United States could insist on new leadership, similar to how Dr. Gro Harlem Brundtland helped to revitalize the WHO at the turn of the 21st century, going after corruption and failing offices and driving forward the first global health treaty to combat smoking. Capping or banning private and multilateral contributions would force the organization to focus on core functions—such as disease reporting, outbreak coordination, and capacity-building for epidemic control.

A reconfigured governance structure that gives member states more authority and oversight, especially over budget priorities, would help to realign the WHO’s mission with genuine global health needs. One way to do that would be to have members’ health ministers and secretaries voting on the highest priorities for spending. This would favor the concerns of emerging nations, who are in the majority, and bring a renewed focus to core issues that matter to them, like vaccine distribution and infectious disease.

It’s also crucial to reckon with America’s own pandemic failings, from questionable research funding at Wuhan’s lab to the widespread—and erroneous—belief that COVID vaccines would completely block transmission, our government agencies bear major responsibility. As part of a process of reform, the Trump administration could commission a full, independent investigation of both domestic and international COVID-19 missteps—including the role played by Dr. Anthony Fauci and his funding decisions—so that we can avoid repeating them.

Leaving the WHO might look like tough talk, but it risks sacrificing the chance to enact meaningful reforms or to shield Americans from future health crises. A more sensible approach is to use American influence to push for decisive changes in Geneva, including new leadership. WHO is best positioned to coordinate exchanges of information from countries that otherwise don’t talk to each other on viruses or other outbreaks. Instead of withdrawing, the Trump administration would do more good by threatening to withhold funding if the agency does not acknowledge its COVID failures, push its leadership to resign, and elect new executives with a mission to overhaul the agency. If the WHO cannot or will not reform, then perhaps the United States can foster a “coalition of the willing” that tackles pandemic preparedness more credibly. But until a proven alternative exists, it’s better to fix the flaws of the only global health body we’ve got. With so many lives at stake, the stakes are simply too high for America to walk away.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.