Almost immediately after assuming the presidency for the second time, President Donald Trump signed an executive order freezing all foreign aid. In the weeks since, according to the New York Times, “The whole system of finding, diagnosing and treating tuberculosis . . . has collapsed in dozens of countries across Africa and Asia.” The consequences of this system collapse in places like Kenya are dismal:

Family members of infected people are not being put on preventive therapy. Infected adults are sharing rooms in crowded Nairobi tenements, and infected children are sleeping four to a bed with their siblings. Parents who took their sick children to get tested the day before Mr. Trump was inaugurated are still waiting to hear if their children have tuberculosis. And people who have the near-totally drug-resistant form of tuberculosis are not being treated.

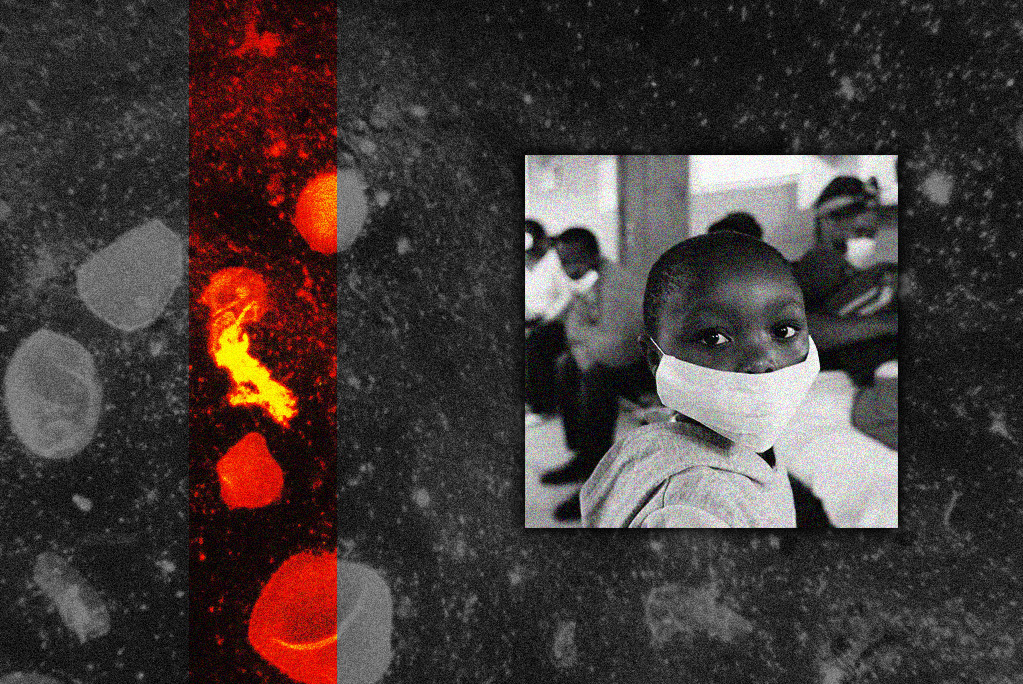

In the West, we often think of tuberculosis as a disease of the past, akin to the Black Death or smallpox (or, until the recent outbreak in Texas and New Mexico, measles). We remember it as “consumption,” that pesky disease that tends to afflict characters in Dickens or Tolstoy novels and kills them, slowly but surely, after they begin coughing up blood. As a result, it’s easy to forget that TB still exists. But in his new book, Everything Is Tuberculosis: The History and Persistence of Our Deadliest Infection, John Green—the YouTuber, podcaster, philanthropist, and acclaimed author of young adult fiction books including The Fault in Our Stars—reminds us that tuberculosis, the bacterial infection that has claimed the lives of as many as 1 in 7 human beings who ever lived, is still very much with us today.

Tuberculosis has always been a challenge to humanity, but as Green notes, what’s different now is that “tuberculosis is curable, and has been since the mid-1950s.” Indeed, because of remarkable medical advances in the 20th century, “[w]e know how to live in a world without tuberculosis. But we choose not to live in that world.” In the United States and other developed countries, we sort of do live in that world: While there were nearly 10,000 cases of tuberculosis in the U.S. in 2023 (a distressing increase of 8.3 percent over 2019 levels), the vast majority of TB cases—Green reports that more than 2 billion people worldwide are currently infected with the bacterial disease (though in most cases the infection remains forever dormant)—occurred in low- and middle-income countries.

One of those countries is West Africa’s Sierra Leone, a former colony for emancipated American slaves who fought alongside the British in the Revolutionary War. Green became interested in TB after meeting a 17-year-old boy there named Henry, who suffered from tuberculosis. Henry had been receiving treatment for several years by the time Green met him, and his prognosis was bleak. The one-two punch of child malnourishment and tuberculosis—“wasting” is “one of the cardinal features of the disease”—left him emaciated, to the point where Green initially thought the young man was around the same age as his 9-year-old son. Worse, Henry had “yellow clouds in the whites of his eyes” due to liver toxicity, a side effect of the drugs used to treat him, and swelling in his neck indicated that TB had invaded his lymph nodes.

Henry was being treated for his disease, but unsuccessfully, and it was determined that he had developed multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. This harder-to-beat version probably afflicted Henry because his father at one point insisted that he abandon professional medical treatment in favor of a faith healer. Indeed, one reason for TB’s longevity is that many patients fail to take their full course of antibiotics. This is especially the case in poor countries, where the DOTS strategy—an acronym meaning Directly Observed Therapy (Short-course)—requires a course of standardized treatment of antibiotics under physician supervision. But in many of these countries, patients struggle to get to and from the hospital to obtain their antibiotics, and their often inadequate food intake makes them susceptible to the nausea that can occur if the medications are taken on an empty stomach, causing them to reject their pills. When TB patients fail to take all their antibiotics, the bacteria that remain replicate, passing on their antibiotic-resistant genes to their progeny.

But rather than lay the blame for TB’s sustained advantage over the human race on patients in poor countries who lack adequate health care, Green argues that “we are in this mess first and foremost because we stopped trying to develop new treatments for tuberculosis.” Green points an accusatory finger at our market-based system of drug development, arguing that there are few economic incentives for drug companies to develop additional TB treatments for people in poor countries. When in 2012 Johnson & Johnson developed bedaquiline, which is effective against drug-resistant tuberculosis (and could have cured Henry within months), the pharmaceutical giant engaged in what Green calls price gouging: It charged $900 for a single course of treatment in low-income countries, far more than the $130 that it charges for the same treatment today. (My inner Kevin D. Williamson insists that this 86 percent price drop is actually proof that the market is working. My inner John Green, meanwhile, wonders whether we should really allow pharmaceutical companies to price life-saving drugs so highly for people who couldn’t possibly afford them.)

Instead of relying solely on market incentives for TB treatment, Green argues, “We could invest more public and philanthropic money into research and development of drugs, vaccines, and treatment distribution systems.” More ambitiously, we could “reimagine the allocation of global healthcare resources to better align them with the burden of global suffering—rewarding treatments that save or improve lives rather than treatments that the rich can afford.” It’s a nice thought, but even before President Trump froze foreign aid, Green’s vision seemed unlikely to manifest anytime soon.

But Trump’s foreign-aid cutoff still spells trouble for affected TB patients. “If left untreated,” Green explains, “most people who develop active TB will eventually die of the disease.” The symptoms vary, but for many patients, “Their lungs collapse or fill with fluid. Scarring leaves so little healthy lung tissue that breathing becomes impossible. The infection spreads to the brain or spinal column.” Others “suffer a sudden, uncontrollable hemorrhage, leading to a quick death as blood drowns the lungs.” And considering that the U.S. contributed about half of all international TB funding in 2024, it’s possible that the death toll this year will exceed even the 1.25 million that it reached in 2023, the most recent year for which data are available.

At the risk of being too alarmist, lackluster treatment of TB in poor countries can have spillover effects in the first world. Tuberculosis is incredibly contagious (Green notes that the average TB patient spreads the infection to 10 to 15 others per year, compared to just 1 for flu and 1.4 to 2.4 for COVID), so as fewer patients get treatment, more of their family members, neighbors, and doctors are at risk of contracting the illness. And as the infection spreads further, it could be only a matter of time before TB reaches our shores with a virulence we haven’t yet experienced. Moreover, the more TB spreads, the more time it has to mutate and become resistant to the antibiotics we currently use to treat the disease. All of which is to say that funding TB treatment and prevention programs in countries like Sierra Leone seems like a wise investment that is, ironically, “consistent with U.S. foreign policy under the America First agenda,” as the State Department put it in a press release on implementing Trump’s funding freeze.

But beyond the strategic benefit to maintaining our status as the world leader in TB treatment and prevention funding, there is also a profound moral case to be made in favor of doing so. The plight of tuberculosis sufferers like Henry may not register in the nationalistic worldview of people like President Trump, Vice President J.D. Vance, or Elon Musk, but that doesn’t mean those patients’ lives aren’t worth saving.

Henry ended up surviving his TB thanks to the tireless efforts of the doctor who begged, pleaded, and cajoled government authorities to get him a course of bedaquiline. It’s unrealistic to expect that all TB patients could be saved this way. But if we stopped treating tuberculosis as though we left it in the rearview mirror decades ago, Henry’s miraculous outcome could become much more routine.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.