Felix Jimenez hadn’t started drinking—yet.

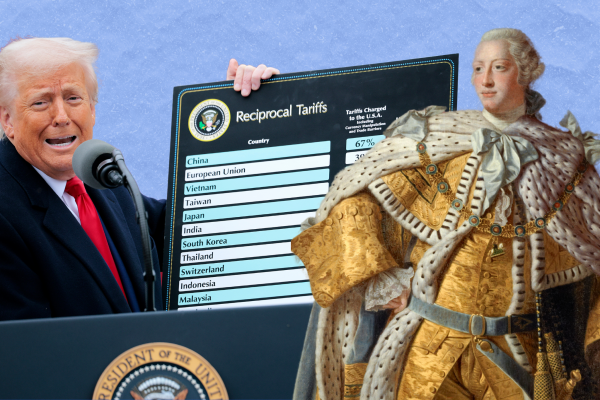

It was two hours before Donald Trump announced his new tariff regime—on the so-called “Liberation Day,” or Wednesday, April 2—and Jimenez, wearing stylish jeans, a blue shirt and a navy blazer, stood behind a table with seven open bottles of Spanish wine in front of him, pouring a couple of ounces for anyone who approached with an empty glass.

I held out my glass and asked Jimenez if he’d answer some questions about the looming tariff announcement. “Well, sure—but I don’t want to get deported,” he joked, though he’s lived in the U.S. for 40 years and is a citizen.

Jimenez was at the National Union Building in Washington, D.C., to promote wines from Castilla y León, Spain—the region that is home to the most underrated red wines in the world. The timing of the tasting was unlucky, coming as it did on the day Trump had promised to share details of his massive new tariff regime—with a potentially devastating impact on the wine industry. The room was highly aware of the possibilities; Emily Nevin-Giannini, who led the guided tasting that kicked off the day, ended her presentation with a nod to the looming announcement: “I super appreciate you guys taking time on this incredibly stressful day for our industry,” she said, “and hopefully you enjoyed this little brain break and that you all get awesome news.”

Jimenez didn’t join me as I sampled the wine—first a crisp white, a Verdejo called La Caprichosa, and then a red, a big, bold Toro called Bucrana—but he acknowledged that depending on the news, he might be drinking heavily that evening. The tariffs, he told me, will mean higher prices and lower margins. “The industry is going to be hurt,” he said. “It’s going to be hard for a few years. People adjust but the problem is that inflation is going to be too much and people are going to be hurt, as a consumer.”

As a producer, he added, he’ll turn his attention elsewhere. “We have already strategized, you know? And I probably will be emphasizing selling in Canada and the Caribbean.”

Pablo González-Calvo, a diminutive Spaniard whose “Wine People” company represents 12 wineries in Spain and sells in 90 countries around the world, was more resigned. There are market disruptions all the time, he said—this one is just bigger. “My friends—they were saying, ‘Are you going to go and speak with Trump?’ And I said, ‘Yes, I’ve been training my handshake’”—with this he squeezed his hand back and forth as if using a grip strengthener—“I will crush him,” he said with a laugh.

“There’s nothing we can do,” González-Calvo added. “He’s going to raise tariffs—that’s a given. With this testosterone level that he has right now, I’m expecting 300 percent.”

By that standard, the tariffs were decidedly Low T. Later that afternoon, six blocks away at the White House, Trump announced 20 percent tariffs on goods from the European Union—roughly in line with the guesses I’d gotten from producers, importers, distributors and other wine industry sources over the previous several days. This wasn’t as bad as it could’ve been—earlier in March, Trump threatened to impose 200 percent tariffs on European wine and spirits, though most everyone understood this to be bluster. (There is still the possibility that Trump will offer additional tariffs specifically targeting wine and spirits from Europe, if the EU makes good on its threats to target American whiskey.)

On the surface, it’d probably be hard to find a less sympathetic industry for tariff opponents to focus on than those in the wine importing business. Nobody’s going to shed any tears for the rich guy with a French wine fetish whose $500 bottle might soon cost $600. But while it’s true that fine wine collectors and those who sell to them can adjust to higher costs, many smaller companies that work in the wine business cannot.

“When you look at $10 spent on wine in the U.S., 80 percent of that $10 is going to U.S. businesses,” says Scott Ades, president of Dalla Terra Winery Direct, a California-based importer specializing in Italian wines. “And so if you put in place a tariff that raises the price of those goods so that they’re no longer affordable, 80 percent of the pain is going to U.S. businesses. If there were tariffs put in place at 50 percent, for example, our company would go out of business.”

“And that would have a chain reaction,” added Ades, who spoke to me from Tuscany. “Distributors would be going out of business, restaurateurs and retailers would be going out of business.” And despite what you might have heard from our president, foreign countries don’t pay these tariffs.

Harry Root learned this the hard way. In 2019, the Trump administration imposed 25 percent tariffs on European wines and spirits as retaliation for what it claimed were unfair trade practices related to a trade dispute involving Airbus and Boeing. (Such head-scratching retaliatory moves are common in trade wars, which are, despite flippant presidential claims to the contrary, not “good” or “easy to win.”) Root, who spoke to me from France, operates “Grassroots Wine” in Alabama and South Carolina. The tariffs were announced while a shipment of wine he ordered was in transit. “We found out that there were 25 percent tariffs being levied,” Root told me, “and at the time we had a container of wine on the water that was worth about $100,000—this is brands that we’ve been working with for years and had built into our market inventory and product that we needed to keep our business sustained. When the tariffs were levied, I was shocked … I realized that the container we had landing just in the next week, that we would have to pay the tariff … 100 percent in full, in cash. There’s no terms for tariffs. And so we were faced—and honestly, [we’re] a really small business, this was a stretch for us—with a tax bill that we had to pay immediately.” (Wine Spectator puts the total cost of those first-term tariffs on wine over 18 months at $239 million—paid by American importers.)

Root currently has $350,000 of wine in transit right now, so with the imposition of 20 percent tariffs announced this week, he’s facing $70,000 in additional taxes the moment that shipment arrives at a U.S. port. And if Trump were to make good on his threat to escalate tariffs to 200 percent, Root could face the prospect of $700,000 in taxes on the $350,000 in wine he ordered before any of these tariffs were announced.

Several of the importers I talked to at the Castilla y León wine tasting had chosen to freeze their orders until they had greater clarity on what the tariffs would look like. “Everything is stopped,” says Jimenez. A saleswoman with a company that specializes in French wines agreed. She described a presentation last week by her company’s owner detailing how much wine they currently have in transit—and she guessed it was about 25 percent of what it would have been otherwise because of the uncertainty on tariffs. (This woman, in the U.S. on a long-term work visa, talked to me on the record and gave me her name and the name of her company. But after criticizing the administration’s tariffs and remembering she’ll be returning from a trip to Europe in two weeks, she asked me not to identify her.)

For Jimenez, just getting a clearer picture of the tariffs means that, in some sense, it really was Liberation Day. “I kind of agree with the ‘Liberation’ because my thought is that we want something,” he said. “I mean, we’ve been suffering since he announced in December, January, so we want to know.”

While Jimenez and his colleagues gained some of that knowledge this week, the issue is not yet settled. On April 13, the EU will announce its retaliatory tariffs—the threatened payback that initially led Trump to threaten the 200 percent tariffs last month. So the new status quo—reduced margins, higher prices, job losses, less selection—may well get worse.

Cheers?

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.