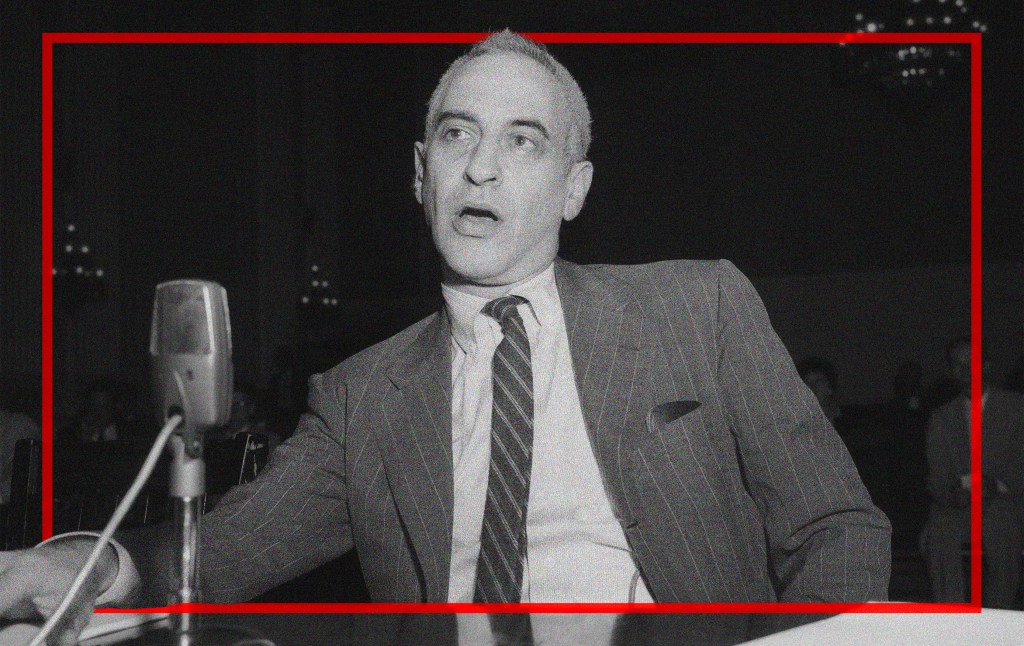

Frank S. Meyer (1909–1972) defined the principles of the conservative intellectual movement in mid-century America, and the idea that conservatism is a “fusion” between traditional religious values and free-market economics owes a lot to his theoretical work. Although Meyer’s writings have received plenty of attention in histories of conservatism, his life has received much less. In The Man Who Invented Conservatism, Daniel J. Flynn sets out to correct the imbalance.

Flynn, a historian and prolific conservative columnist, discovered Meyer’s personal papers stored away in a Pennsylvania warehouse in 2021. These materials allowed him to piece together what happened during the first part of Meyer’s life, before he became famous as a conservative author, activist, and editor at National Review.

Meyer was born into privilege in Newark, New Jersey. At 17 he left his hometown for Princeton University, but dropped out after about a year. He then went to England and studied philosophy, politics, and economics at the University of Oxford, graduating in 1932. He spent the next decade or so as a Stalinist organizer, unsuccessful graduate student, and general playboy.

Sometimes the three identities overlapped. As a prominent leader in the communist student movement, Meyer was something like friends-with-benefits with Sheila MacDonald, daughter of then-prime minister Ramsay MacDonald—while pursuing many other women at the same time. His communist activism involved (among other things) writing and editing articles for magazines, teaching Marxist theory to the young, recruiting members to join Soviet-led groups, and signing people up to go fight for the left in the Spanish Civil War.

Between the womanizing and the political agitation, Meyer didn’t leave much time for his graduate studies—and this despite many entreaties from professors telling him to submit his homework. “The man who invented conservatism conducted himself in ways, at least prior to the penitential second act of his story, offensive to those who embrace that label,” Flynn writes. He finds little to admire in Meyer’s early years.

Meyer’s eventual break with communism occurred during the 1940s. There doesn’t appear to have been a decisive event that changed his worldview, an identifiable moment of epiphany, but Flynn points to some factors that might have played a role. In 1942, for example, Meyer tried to join the U.S. Army. He attended training camp, but he lacked the requisite physical fitness and was promptly dismissed from service. However, his brief Army stint exposed him to people from the working class, and he came to see that they were nothing like the proletarians described by Marxist dogma. Another factor was Meyer’s reading of Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom and Richard Weaver’s Ideas Have Consequences. At any rate, by the end of the decade Meyer was officially testifying to the U.S. government about illegal communist activity.

In 1955, Meyer published a critical review of Russell Kirk’s The Conservative Mind, charging Kirk with writing in a highfalutin rhetorical mode that made it difficult to pin down his concrete policy beliefs. “The fundamental political issue today,” Meyer wrote, is between “collectivism and statism … and the principles of the primacy of the individual, the division of power, the limitation of government, the freedom of the economy.” Kirk’s conservatism did not explicitly come out in favor of individualism and capitalism, and in Meyer’s judgment this was precisely what the political situation demanded. His ideological commitments had indeed traveled a long way.

Meyer’s most sustained theoretical effort came in 1962 with the publication of In Defense of Freedom, a book to which Flynn devotes an entire chapter. Two of his arguments stand out. First, Meyer tried to fuse traditionalism and libertarianism by holding that while the ultimate goal of private life is to attain virtue, the proper goal of the state is to protect people’s individual liberty. Thus, in our personal lives we should strive to act in accordance with the demands of morality and to develop our talents—that is, after all, the definition of virtue. Our political arrangements, on the other hand, should preserve our freedom to choose, even when that means our freedom to make immoral decisions. True virtue must be freely chosen, so we are not virtuous if the state forces us to pursue a certain life path.

Such was Meyer’s synthesis of freedom and tradition: liberty in the public sphere, virtue in the private.

Meyer’s second key argument is that fusionist conservatism is, at bottom, an articulation of the most compelling ideas in both the American political tradition and in Western civilization more broadly. American conservatives are indeed defenders of tradition—but it is a tradition of individual liberty, embodied in the institutions of the Founding. Flynn approves of this claim’s patriotic flavor, writing “The underlying idea that the American Founding’s significance involved advancing freedom and that American conservatives necessarily find freedom as their nation’s tradition attracted conservatives because of its simplicity and truth.”

Flynn’s sympathetic tone here comes as somewhat of a surprise. The prose in this biography contains more than a hint of cynicism, a sort of generalized contempt for the stupidity of man. For instance, Flynn makes fun of the young Meyer’s attempts at keeping girlfriends everywhere he went: in France, in England, and in America. Commenting on a particularly clumsy letter to a girlfriend in France, Flynn (rather brutally) writes that “It all sounded like a young man cartoonishly devoid of romance attempting to alchemize his deception into truth.” But the cynicism evaporates in his account of In Defense of Freedom.

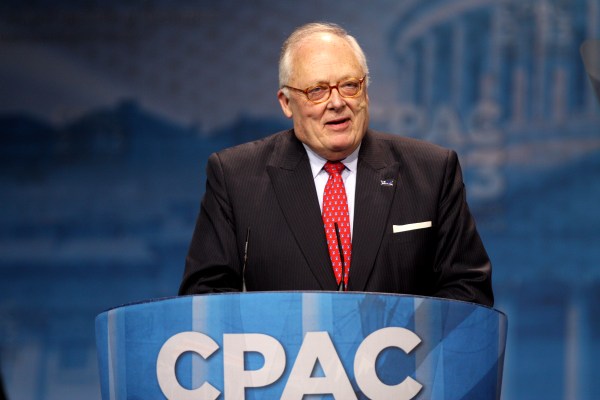

Meyer did more than write philosophical treatises in the 1960s. Drawing on his experience as a communist organizer, he sought to build up conservative institutions. He participated in the creation of Young Americans for Freedom and the American Conservative Union, which would in turn launch the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC). He held court with ambitious young conservatives in his home at Woodstock, New York; many of them would go on to occupy leading positions in the conservative movement. In his role as editor of National Review, he promoted writers such as Joan Didion and Garry Wills.

He also thought deeply about how to get proponents of fusionist conservatism into power, and specifically into the presidency. He supported Barry Goldwater’s presidential ambitions, judging that he was the best political vehicle for conservatism. When Goldwater was crushed in the 1964 presidential election, Meyer was undeterred: He thought that conservatism had a genuine path to the presidency, if only it persevered. He was vindicated in 1980, when Ronald Reagan won the presidency. But Meyer didn’t live to see it.

Flynn’s excellent book has given Meyer’s life the attention it deserves. Yet for a biographer who doesn’t shy away from sharing his opinions, there is a curious omission in the book: Flynn says little about Meyer’s significance for us today. Flynn is surely among the most knowledgeable observers of the conservative movement, and he likely knows more about Meyer than just about anybody. What would Meyer have said about today’s conservative landscape? Would he have seen MAGA as a fulfillment or betrayal of his worldview? If Meyer created conservatism, it’s hard not to wonder what he would make of his invention today.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.