For the last few years, experts have been fighting a battle over the impact of social media on young Americans.

On one side of this battle, there were psychologists, like Jonathan Haidt, who have forcefully argued that social media has terrible impacts on young people. As Haidt writes in The Anxious Generation, which has continuously been on the New York Times bestseller list since its release more than a year ago, adolescents have experienced rising rates of anxiety, depression, and self-harm over the past decade. The reason, according to Haidt, lies in a “great rewiring” of childhood, rooted in the rise of social media and the decline of in-person play.

On the other side of this battle are the skeptics who point to our collective tendency to exaggerate the impact of new technologies, and catastrophize their effects. If you go back through history, skeptics like Tyler Cowen have pointed out, you can find people complaining that there is “something wrong with young people these days” at every historical juncture. And even if they were well aware of that tendency, each generation has historically been tempted to insist that there was something about its particular time and place which made that complaint uniquely justified.

In this battle, I have until now chosen to be a non-combatant. While I always found Haidt’s worries to be plausible, I also felt that we didn’t yet have enough evidence to be confident that things were really as bad as he feared.

And then I came across a truly jaw-dropping chart.

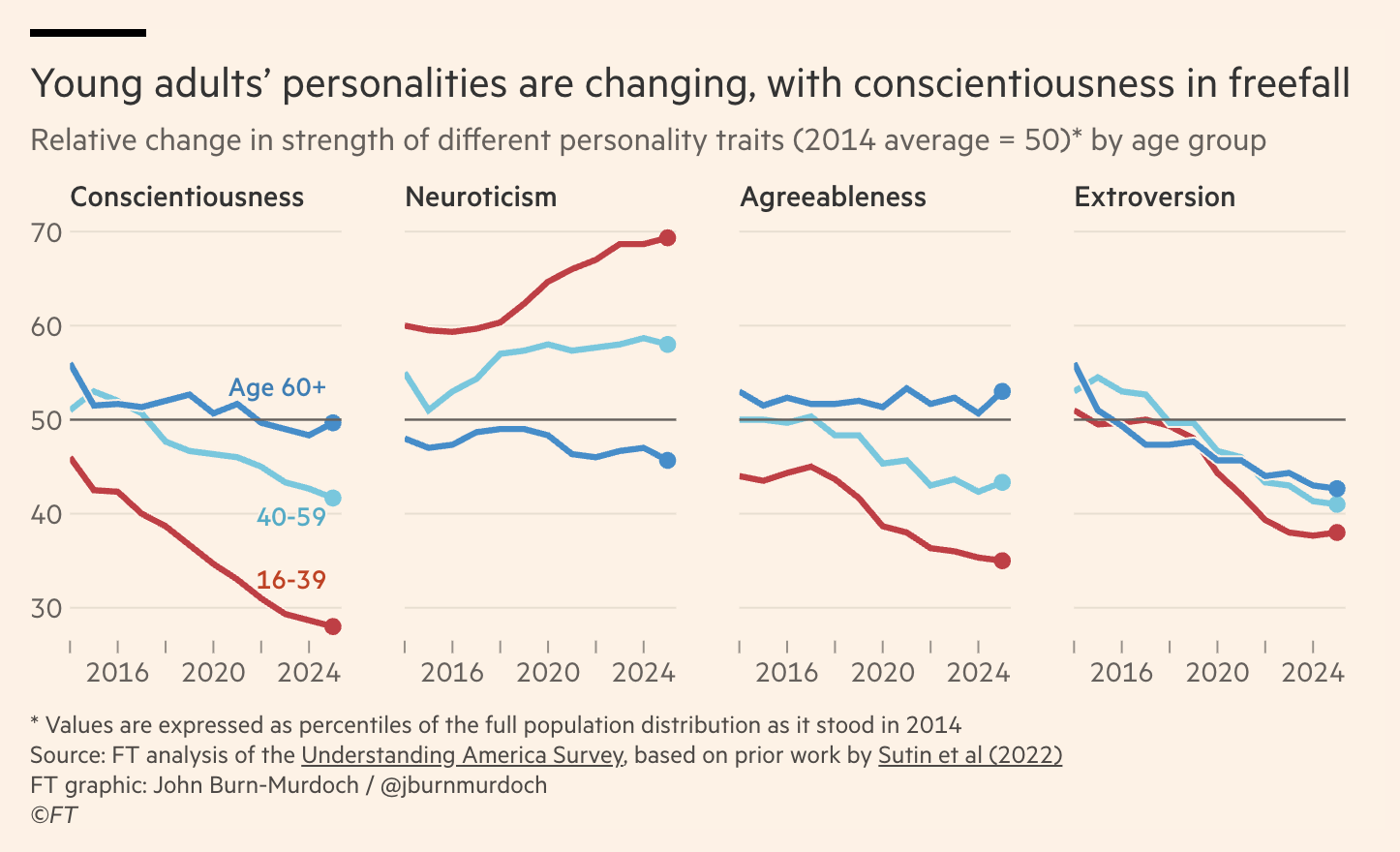

That chart, published by Financial Times journalist John Burn-Murdoch and based on his analysis of data from the extensive Understanding America Study, shows how the traits measured by the personality test most widely used in academic psychology have changed over the past decade. The OCEAN test measures five things: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Decades of research have demonstrated that some of these traits are highly predictive of life outcomes; in particular, conscientiousness (“the tendency to be organized, responsible, and hardworking”) predicts everything from greater professional success to a lower likelihood of getting divorced. Extroversion (a tendency to be “outgoing, gregarious, sociable, and openly expressive”) is associated with better mental health, broader social networks, and greater life satisfaction. Meanwhile, neuroticism (understood as a propensity toward anxiety, emotional instability, and negative emotion) is strongly correlated with negative outcomes, such as higher rates of depression, lower life satisfaction, and poorer overall mental health.

With these facts in mind, you will quickly realize why Burn-Murdoch’s chart demonstrates that something very, very concerning has been happening to young people.

What Burn-Murdoch shows is that the traits most strongly predictive of positive outcomes are in sharp decline. Young people, in particular, have become far less conscientious and extroverted over the past decade. Conversely, the trait most strongly associated with negative life outcomes, neuroticism, has sharply increased. To put it bluntly, the average 20-year-old today is less conscientious and more neurotic than 70 percent of all people were just a decade ago.

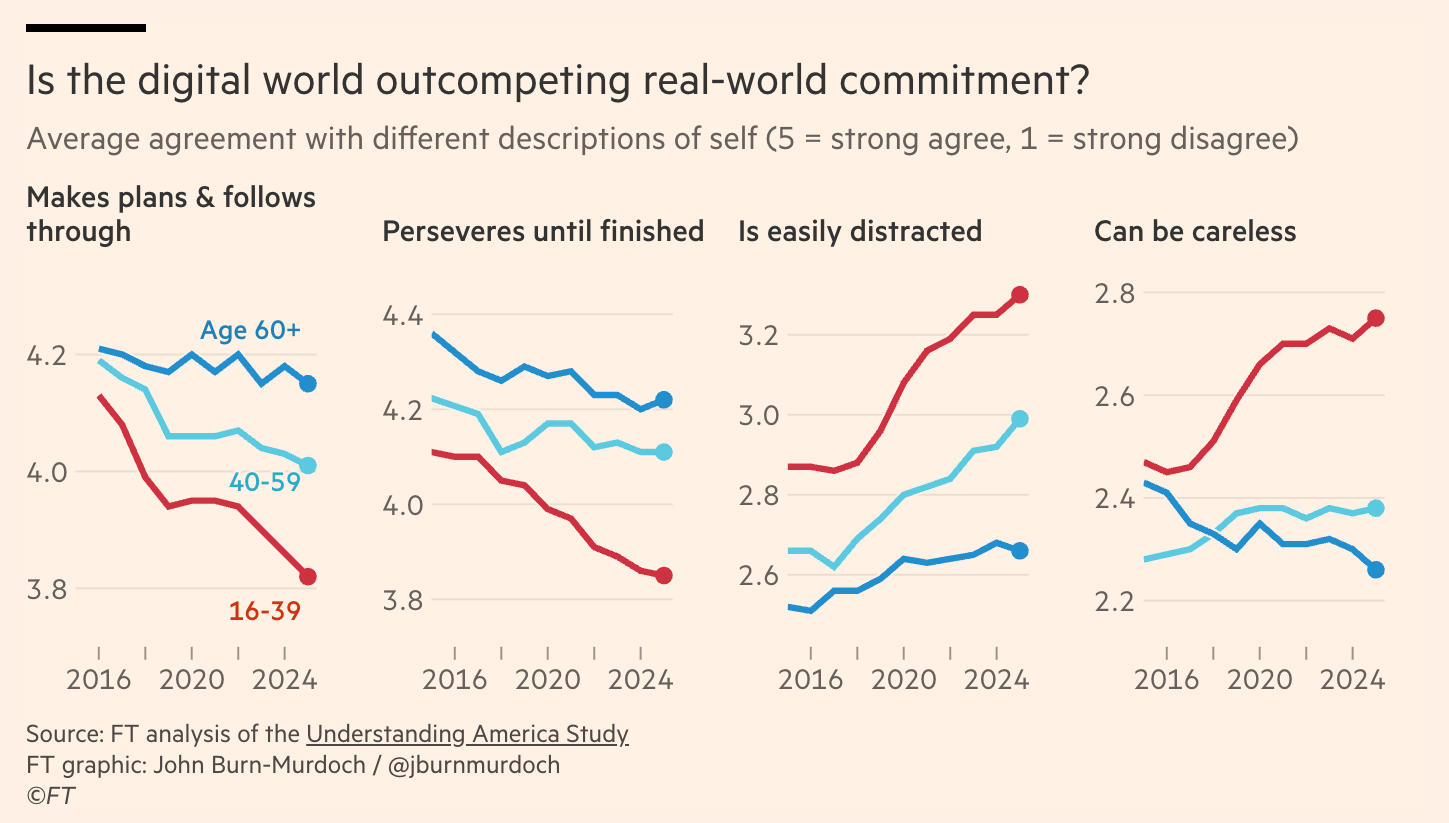

Personality tests writ large have gotten a bad rap, sometimes for good reason. But there is a huge body of evidence that these metrics, when reported by trustworthy experts, really are meaningful. And if you break somewhat nebulous-sounding categories like “conscientiousness” down into their constituent parts—which Burn-Murdoch did, in subsequent charts following the one above—it is easy to see why. It is hardly a stretch to imagine that young people who, by their own admission, find it much harder than their elders did at a similar age to “make plans and follow through on them,” or to “persevere with a task until it is finished,” may struggle at many core tasks that life throws at them.

This data doesn’t prove that these shifts in personality are driven by social media. But two details do point in that direction. First, some of the most obvious alternative explanations don’t seem to hold water. Some experts, for example, have argued that the global pandemic is to blame for some of the alarming changes in young people. But while this is plausible, most of the worrying changes noted by Burn-Murdoch set in well before 2020. Second, young people spend much more time on social media; and while many of these changes in personality are evident across generations, they turn out to be concentrated precisely among that age group that spends the most time online. All in all, it is hard to imagine what social transformation other than the rise of social media could have caused these changes.

What this data shows is not just that we should be very worried about the future of young people in America; it is that we have fundamentally misunderstood the impact that the internet would have on our lives. By all appearances, the very tools we built to connect us are, in practice, turning us into the worst version of ourselves.

It is now hard to remember the optimism with which many people greeted the arrival of the digital world. But back in the 1990s and early 2000s, the evangelists of the internet confidently predicted that the internet would, as Thomas Friedman wrote in The Lexus and the Olive Tree, published at the cusp of the new millennium, “weave the world together.”

With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to make fun of such predictions. But the logic for these predictions was seemingly compelling. For all of human history until recently, it had been extremely costly and cumbersome for people in different parts of the world to communicate. As late as 1930, Friedman pointed out, a three-minute phone call between London and New York cost about $300. That made it hard for people to develop a greater understanding of each other, or to recognize that they might share all kinds of interests.

By the time Friedman was writing, such a phone call was basically free. It was easy to imagine that, in a world of costless communication, most people would choose to connect with people in faraway locations who are very different from them. Society would, the hope went, grow to be far more cosmopolitan: far more interested in the well-being of people unlike ourselves, and far less likely to prioritize those who share our group identities.

The truth, as we now know, turned out to be very different. Given the opportunity to communicate with anybody they wish, most people are spending their time on social media connecting with people they already know, with those who share their identities, or with those who share the exact same political views. The greater ease of communication was supposed to help the human species transcend its traditional boundaries and expand our collective horizons; instead, it has amplified our tribal instincts and turned every aspect of our politics and culture into a fevered battle between the in-group and the out-group. Early evangelists of the internet conjured up a touching vision of universal human connection. Instead, the technology they rhapsodized has turned us into tribalist creatures, giving ever greater importance to our race, our gender, our sexual orientation, and our political convictions.

Even as the first big predictions about the internet were starting to prove wrong, commentators persisted in assuming that they could foresee the effects of new developments in the digital realm. Take the case of online dating.

The first online dating services, like Match.com, started to appear in the 1990s, and they began to lose their social stigma over the course of the 2000s. Even then, it took a while for them to become dominant. It wasn’t until the early 2010s that meeting online became the most common way in which couples formed—but the share of couples who meet online has continued its exponential ascent ever since.

When online dating went mainstream, many commentators assumed that it would lead to a lot more relationships, or at least to a greater number of hookups. One group of American psychologists argued in a 2012 assessment that online dating “offers unprecedented (and remarkably convenient) levels of access to potential partners.” Their main worry was that online dating might make people more likely to play the field indefinitely: “The ready access to a large pool of potential partners can elicit an evaluative, assessment-oriented mindset that leads online daters to objectify potential partners and might even undermine their willingness to commit to one of them.”

The logic that fueled this early assessment is obvious enough. In the real world, a person’s dating pool is restricted to people they physically encounter, and it can take considerable courage to ask somebody out. In theory, online dating services should greatly expand the dating pool and reduce the fear of rejection. It stands to reason that this should lead to more couples forming, or at least to people having more sexual encounters.

But the impact of online dating has turned out very differently. Young people today are less likely to be in a stable relationship than they were a few decades ago. While nearly 4 in 5 Boomers had a romantic partner for some or all of their teenage years, for example, only about half of Gen Zers had a boyfriend or girlfriend in high school—and there are strong indications that this decline in couple formation persists as young people become adults. According to a 2023 Pew survey, for example, the share of 40-year-olds who have never been married has significantly increased over the past decade.

As those psychologists pointed out during the advent of online dating, one reason why there are so few couples forming today might be that, with endless options, people might find it much harder to commit to one partner. Perhaps people aren’t forming stable bonds because they are hooking up with an endless stream of strangers?

Oddly, that doesn’t seem to be happening either. In fact, it seems today’s young people are much less likely to be sexually active than they were in the past. According to one study, from 2013 to 2015, 9 percent of men aged 23 to 32 hadn’t had sex for the past 12 months; in the latest data, from 2022 to 2023, the share of similarly aged men who had not had a sexual partner for the past 12 months had jumped to 24 percent.

But America isn’t just going through a romantic drought; it’s also experiencing a social one. As Derek Thompson has recently shown, Americans have become much less likely to spend time socializing with friends or neighbors over the last two decades. And while this trend holds for Americans of all ages, it is once again especially pronounced among the young: Those aged 15 to 24, for example, now spend a staggering 69 percent less time attending or hosting a social event than similarly aged Americans did two decades ago.

The internet was supposed to make us realize how much we have in common with those who are very different from us. It was supposed to make it easier to find romantic partners and friends. And all of that was supposed to turn us into better versions of ourselves.

The truth has turned out to be radically, and depressingly, different.

Despite making communication virtually costless to the average consumer, the internet has inspired a worldwide return to identity and tribalism. Though it presents us with an endless stream of potential romantic partners, it has left more people single and celibate. While it makes it easy to find people who share the same interests, it has made people far less likely than in the past to socialize “in the real world.” And all of that has somehow led young people to cultivate personality traits, like neuroticism, that make them increasingly ill-equipped to face the world.

That is an astonishingly negative balance sheet. But there is one small ray of hope. Perhaps two decades of data give us enough information to make more accurate predictions about the long-term impact of the internet than we could have done at the dawn of the digital age. But we would do well to remember that we have, so far, gotten the impact of the internet badly wrong at every stage. And we still stand at the cusp of the digital age, with the rise of artificial intelligence likely to transform our world as fundamentally as did the invention of social media. Might we eventually figure out the habits, norms, and regulations needed to soften the remarkably destructive impact that the internet has so far had on society?

Given how badly things are going, that seems unlikely. But I don’t want to rule out that some form of deliverance may be hiding behind the next historical corner. For if there’s one thing that the brief history of the internet has taught us, it’s that we find it nearly impossible to predict the social impact of such revolutionary changes in technology.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.