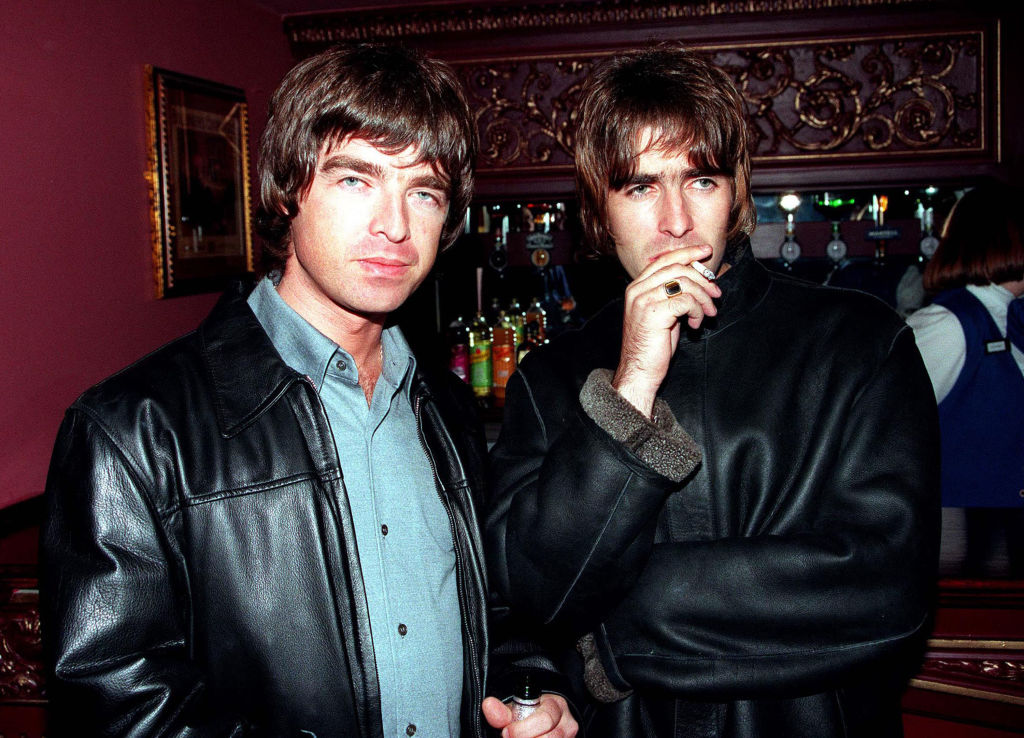

It’s been a big week for Oasis fans. On Tuesday, the group that once reasonably, if immodestly, billed itself as the greatest rock band in the world announced that it would be reuniting for a series of shows in 2025, more than 15 years after its last live performance. This was a minor miracle: Few people ever thought there could be a ceasefire between the feuding siblings at the band’s core, Noel Gallagher and his younger brother Liam. What’s more, the announcement arrived just days before a 30th anniversary reissue of Oasis’ debut album, Definitely Maybe. The confluence of these events is a good opportunity to consider what exactly made that debut album such a success, and why it’s still enjoyable three decades later.

Oasis started in the early 1990s without Noel. He was the roadie for a moderately successful Manchester band (Inspiral Carpets) when he learned that Liam had booked a gig with a band of his own. Noel attended their first show and, to his surprise, saw promise. He first joined Liam and his bandmates—guitarist Paul “Bonehead” Arthurs, bassist Paul “Guigsy” McGuigan, and drummer Tony McCarroll—for jam sessions before becoming the band’s songwriter and lead guitarist. The group landed a record deal in 1993 almost by accident: Alan McGee, co-founder of Creation Records, happened to be at a Glasgow club the night Oasis’ members talked their way into performing an unscheduled set. Impressed by Noel’s songs and the band’s brash style, McGee signed them that night.

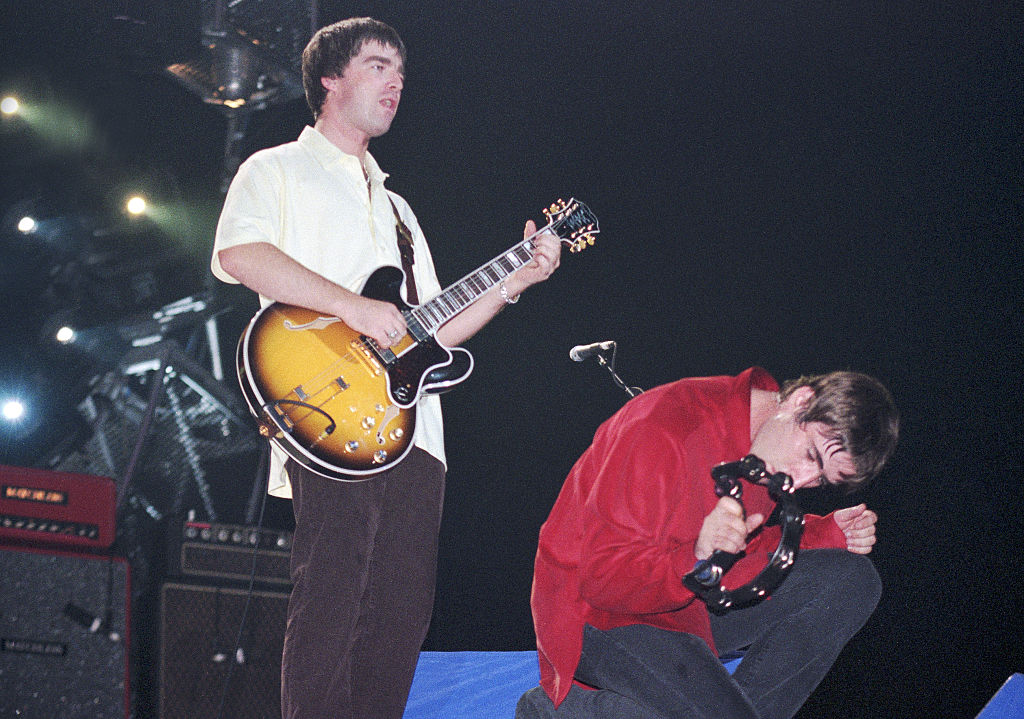

Recording for what Noel calls “the definitive Oasis album” did not begin well. The first sessions, in January 1994, failed to capture the group’s energy. They tried again the following month, this time with the band playing live in the same room and Noel co-producing with the band’s live engineer. That fell flat, too. Noel grew frustrated; McGee grew worried. So they brought in outside producer Owen Morris (whose CV included work with Noel’s guitar hero, Johnny Marr) to finally coax the master tapes into conveying the band’s bravado. Rollout for the album began that spring, with live television performances and the release of early singles.

Oasis had impeccable timing. The wave that became known as Britpop was already rising. In reaction to the American invasion of grunge, and with dreams of a Labor-led Britain, English bands like Suede, Blur, and Elastica were producing rock songs that showcased distinctively British sensibilities and accents. But these bands tended to be London-based, experimental, and ironic; Oasis was Northern, working class, and unsubtle. They were, as Sleeper frontwoman Louise Wener put it, “the chavs of Britpop.”

Oasis’ contrast with grunge is also illustrative. Seattle exported dark, sludgy guitars; Noel’s and Bonehead’s are loud but lighter. And while Nirvana and Pearl Jam seemed to resent their own success; Oasis bragged about it even before they had it. “Tonight,” Liam boasts on one track, “I'm a rock ‘n’ roll star.” The band released its first single, “Supersonic,” only days after Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain killed himself—a morbidly appropriate coincidence. “I have never failed to fail,” Cobain sang in the last song he recorded. “I’m feeling supersonic,” Liam declares in his debut.

“Supersonic” cracked the top 40 of the U.K. singles chart and its follow-up, “Shakermaker,” just missed the top 10. “Live Forever”—the decade’s contra-Cobain anthem—arrived in early August, reaching No. 10 in the U.K. and No. 2 on America’s Alternative Airplay chart. (Not to be overlooked: many of the B-sides that accompanied the singles, like “D’Yer Wanna Be a Spaceman,” “Listen Up,” and “Fade Away,” would have been A-sides for any other band.) By the time Definitely Maybe was released on August 29, an audience was ready. In the U.K., the album sold 86,000 copies in its first week, setting a new record for debut albums by a British artist.

Noel has recently described Definitely Maybe as “an honest snapshot of working-class lads trying to make it.” His lyrics convey irresistibly contagious defiance, as in “Bring It On Down”

You’re the outcast

You’re the underclass

But you don’t care

Because you’re living fast.

Or the chorus of the album’s fourth single, “Cigarettes and Alcohol”:

Is it worth the aggravation

To find yourself a job when there’s nothing worth working for?

It's a crazy situation

But all I need are cigarettes and alcohol.

Every song expresses that self-assurance and (except for the cheeky final acoustic track) is turned up to 11. Every chorus is as big as the brothers’ monobrows. The album does not have sonic range or thematic variety—those would have to wait until (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, the band’s second album. Definitely Maybe does one thing and it does it well. As the American music critic Steven Hyden put it, “They were making a persuasive case for life. … What Oasis promised was self-actualization.” A crucial element of that attitude is Liam snarling the lyrics with an arrogance as brazen as his accent. (Liam doesn’t like sunshine; he likes sun-shee-ine.) More Johnny Rotten than John Lennon, he makes even the most absurd lines—“I know a girl named Elsa / She’s into Alka Seltzer”—absolutely convincing.

Oasis is often disparaged as merely ripping off the Beatles. But reducing the group to a Fab Four tribute band is insulting—Oasis ripped off so many other bands, too! On Definitely Maybe, you hear a melody cribbed from the Rolling Stones, a riff ripped from T. Rex, and even lyrics from Monty Python. Another melody is lifted from the New Seekers’ “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing”—you know, the song from the Coke ad Don Draper wrote? But good rock bands borrow while great rock bands steal, and Oasis pilfers widely without sounding like anyone else.

Later in the ‘90s, the English philosopher Roger Scruton complained that Oasis’ music “is put together from stock devices that are available to any amateur rock musician, as part of the tools of the trade.” Their fans “do not require from Oasis any other sounds than those that the group so reliably provides for them.” Scruton elsewhere complained that in a pop culture that elevates youth above all, a fan’s “totems must be formed in his own image—perpetually young, perpetually transgressive, perpetually incompetent.” Ouch.

He has a point, though. Oasis succeeded not because it was musically original or because its lyrics were poetic. Instead, it expressed a youthful recklessness in an especially evocative way at a time when music fans wanted to hear precisely that. There are obvious limits to the “self-actualization” Oasis expresses, as the band itself showed: It nearly broke up during the tour for Definitely Maybe, after Liam and Noel fought during a meth-fueled show in Los Angeles. (“Noel has a lot of buttons. Liam has a lot of fingers,” said one person close to the band.) As usual, listeners are better off enjoying the vices of rock stars vicariously.

But even after Oasis’ original fans have probably found richer, more sophisticated cultural experiences and deeper sources of personal satisfaction, the defiance of Definitely Maybe still feels fresh and invigorating. That’s one reason the band’s reunion is so exciting. In the meantime, fans will make do with the 30th anniversary reissue of the album, complete with outtakes from the failed first recordings, scheduled to be released this weekend.

Lasting 30 years isn’t the same as living forever, but it’s not bad for a batch of youth anthems.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.