In his seminal 1989 book The Democratization of American Christianity, historian Nathan Hatch posited that the forces of democratization and religious disestablishment unleashed by the American Revolution galvanized an unprecedented outpouring of spiritual enthusiasm. By untethering government and religion, the American Founders created a marketplace of faiths that proved powerfully adept at channeling Americans’ religious longings. In Hatch’s telling, the Methodists, Baptists, Latter-day Saints, and other popular religious movements that defined the first few decades of the American republic comprise “a story of the success of common people in shaping the culture after their own priorities rather than the priorities outlined by gentlemen such as the framers of the Constitution.”

But as Jerome E. Copulsky notes in his new book, American Heretics, this interpretation of the founding’s religious implications has always had its critics. Stretching from the Revolutionary period to the internet age, his narrative is an incisive history of the clergymen, politicians, and intellectuals who have cast the American project not as the guardian angel of religious expression, but rather a devil in disguise.

Although Copulsky focuses primarily on Christian thinkers, his study shows how they levelled a wide range of assaults on some of the foundations of American governance codified in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. He convincingly portrays these figures as snakes in the American garden. In doing so, however, he misses an opportunity to interrogate the photonegative image of the United States that their critiques reveal. These men may be heretics, but the American orthodoxy they are dissenting from is not limited to the staid principles of our founding documents.

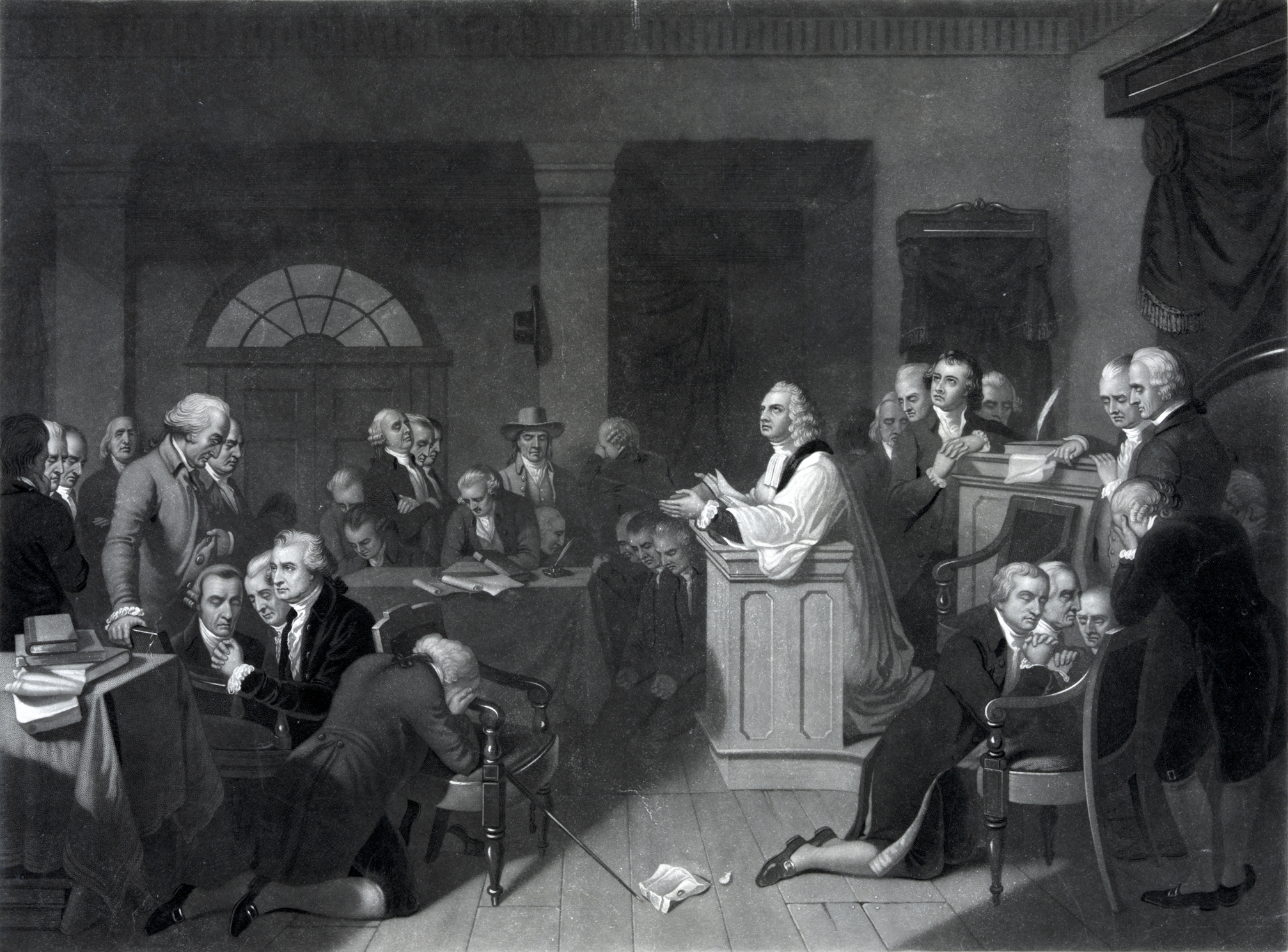

A key commonality among American Heretics’s subjects is the belief that the Revolutionary generation committed a founding sin in refusing to use the weight of the federal government for religious ends. Eighteenth-century Anglican loyalists and 19th-century Catholic traditionalists both balked at the American rejection of a government entwined with a state religion. Presbyterian Covenanters and Protestant Reconstructionists waged lengthy political and intellectual campaigns to rededicate American governing institutions to Christianity. And a cadre of contemporary postliberals have lobbed viral invectives against the decadence engendered by American religious pluralism.

Even as Copulsky seems particularly unnerved by the postliberals, the Reformed Presbyterians, or “Covenanters,” stand out as the book’s most intriguing antagonists of the American regime. Believing that civil authority emanated from Christ, Covenanters argued from the 1790s onward that they could not support a Constitution that failed to articulate the nation’s dependence on God (they were also troubled by the document’s silent sanction of slavery). They struggled for nearly a century to amend the Constitution so that it would declare Jesus Christ “as the Ruler among the nations.”

By appending the language of divine monarchy to the Constitution, the Covenanters sought to upend its encapsulation of American political theory, which locates sovereignty in the people rather than in a single ruler. Their political theology also offered another significant departure from the founders’ vision. In Federalist 51, James Madison asserted that “if men were angels, no government would be necessary.” But as the minister Samuel B. Wylie argued in The Two Sons of Oil, an infamous Covenanter tract published in 1803, a divine form of civil government existed prior to man’s fall. “Man’s subjection to the moral government of his Maker would have been similar to that of beings of a more dignified order,” he concluded. Even angels needed government.

The Covenanters fundamentally rejected Madison’s suspicions of political power and understanding of government as a flawed institution that was both constituted by and served flawed people. They instead embraced government as an extension of divine rule and treated social contract theory as a kind of heresy promulgated by Enlightenment theorists that unacceptably elevated humanity above God. Although Copulsky does not identify them as such, the Covenanters represented a flavor of the postmillennialism that dominated American Protestantism in the 19th century, which held that Christ would return to earth after a 1,000-year reign of peace ushered in by the proliferation of Christianity.

Despite sharing a postmillennial outlook, the 20th century Christian Reconstructionists whom Copulsky also examines were less interested in working through the institutions of American government than in abolishing them altogether. The violent discord of the public school “Bible Wars” of the late 1860s sparked a pattern of government secularization that culminated in a series of postwar Supreme Court cases restricting religion in state-level public institutions. Although anticommunist sentiment facilitated the inclusion of “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance in 1954, the Calvinist theologian R.J. Rushdoony pushed back against the supposedly growing godlessness of American society by building an intellectual network in the 1960s dedicated to refounding the United States under the aegis of theonomy, or the rule of Mosaic and New Testament law. Rushdoony’s vision of an America governed in all respects by Christian teachings not only eliminated religious liberty and distinctions between private and public life, but the very concept of a legislative branch. Families and churches would depend on tithes to run schools, hospitals, and other social services, while the government would be restricted to national defense and the enforcement of biblical law.

The Christian Reconstructionists’ disregard for the nation’s first branch points to another point of convergence among Copulsky’s heretics: a skepticism of human equality and corresponding governance through the mediation of “common” political sense. It is unsurprising that American Heretics primarily profiles well-educated men pursuing elite professions in ministries or universities, who contra William F. Buckley were quite intent on immanentizing the eschaton. Copulsky wants us to reckon with the threat these well-connected men have presented to liberal democracy, arguing that their “dreams of order can beget nightmares of chaos.” But despite the impressive volume of their writings, it is unclear just how influential their elegant jeremiads have been on the course of American history.

In fact, failure dogs the figures in Copulsky’s narrative. In 1831, a mob burned the Covenanter minister James Renwick Willson in effigy for criticizing George Washington and Thomas Jefferson as infidels. The Christian Amendment movement was basically dealt a fatal blow in 1874 when the House Judiciary Committee concluded that the United States was founded “to be the home of the oppressed of all nations of the earth, whether Christian or Pagan.” Triumph, the Catholic integralist magazine founded in 1966 by the Franco-sympathizing Leo Brent Bozell, shuttered after 10 splenetic years. And infighting between Rushdoony and his ally and son-in-law Gary North (who lambasted Hatch and his fellow evangelical historians as “intellectual schizophrenics”) tore the Christian Reconstructionist movement apart.

Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed may have landed on Barack Obama’s reading list, but Copulsky admits that there is not much of a political future for the brand of “aristopopulism” peddled by him and fellow Catholic intellectuals such as Adrian Vermuele. “Vermeule and his allies do not appear to seriously consider that they are dreaming within a historically Protestant country,” he pointedly notes.

But it’s worth remembering that the figures who came closest to realizing their brand of American heresy were Southern pro-slavery theologians. Copulsky traces how Southern ministers such as Benjamin Palmer and Frederick A. Ross bolstered the ideological cornerstone of the Confederacy by mobilizing justification for African enslavement from Genesis and the Gospels. They also vacillated between restricting the Declaration’s claim of equal rights to the colonial Revolutionaries and their white American descendants and asserting that the Declaration was simply irreconcilable with Christian teachings on the social hierarchies God had ordained to govern a fallen world.

Copulsky labels these men as American heretics for rejecting the Declaration’s ideals. In doing so, he implicitly overestimates the extent to which abolitionism and teachings of racial equality were popular in contemporary Northern churches. The long struggle after the Civil War to secure the Declaration’s “promissory note” of full civil rights for African Americans furthermore invites an unsettling question: In a democracy, who has the authority to separate the wheat from the chaff of American civil religion?

American Heretics ultimately suggests that apostasy in America has more to do with function than with form. To “expect the populace to be tutored and trained by wise and enlightened rulers” of postliberalism, Copulsky concludes near the end of his book, is a kind of modern idolatry. By contrast, the lay preachers of Hatch’s history who turbo-charged the Second Great Awakening were “folk geniuses” whose blend of “coarse language, earthy humor, biting sarcasm, and commonsense reasoning” enraptured American audiences and frightened traditional churches. “Who would wish to attack a windmill?” a Congregationalist minister once complained about his evangelical rivals. “Who can refute a sneer?” He was writing in 1817, but he might as well have been describing the populist prophets who reign in our own time.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.