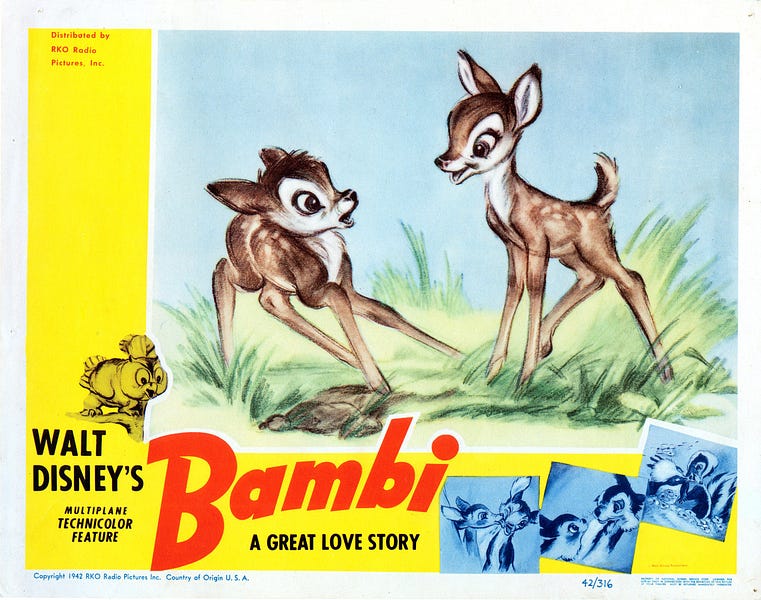

When I first saw Disney’s Bambi as a child, the whole cinematic experience was overshadowed by the emotional wallop of watching Bambi lose his mother. More like an old fashioned Grimms’ fairy tale than a typical, modern kids’ movie, Bambi planted the terrifying and highly realistic fear of losing a parent. And yet, Disney’s movie is saccharine compared to the adult novel on which it’s based.

The Original Bambi: The Story of a Life in the Forest, was recently translated by Jack Zipes, professor emeritus of German and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota, to mark the centennial of Bambi’s original publication. Written by Felix Salten—who had culturally camouflaged his Jewish birth name of Siegmund Salzmann—Bambi is a poignant allegory of Jewish life in Europe.

Born in Pest, Hungary, and raised in Vienna, Austria, Felix Salten was an author molded by the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As a journalist and outdoorsman who enjoyed hunting, Salten also wrote as a careful observer. In Bambi, readers peer into the harsh existence of Salten’s beloved forest animals, as well as the precarity of European Jewish life during the early 20th-century. The story is substantive and thought provoking, and both the imagery and Salten’s writing skill are apparent, even through the barrier of translation. Like many other highly culturally specific stories, Bambi’s well-written particularity offers readers universal relatability.

We see and hear the whole forest. Butterflies are like “wandering flowers.” Birds make distinct sounds, including “the loud laughter of the woodpecker and the joyless call of the crow,” as pheasants “shrieked, and it seemed that their throats would burst.” Bambi’s friend Hare, who has “long spoon-ears” is described as “very genteel.” Even the leaves discuss what happens after falling, since no fallen leaf “‘ha[s] ever returned to tell us about it.’”

Bambi tells the story of life in the forest through the eyes of a male fawn, who grows up to become a prince of the forest, as stags are called here. Reflecting reality, young Bambi spends significant time with his mother, as stags don’t help raise their offspring. Bambi’s mother is his teacher, answering his many questions and helping him understand the world around him. She teaches Bambi to respect the stags, to befriend smaller animals, and how to survive. For example, Bambi must learn how to sniff the air to detect nearby danger and how to safely spend time in an open meadow. After young Bambi sees a polecat kill a mouse, his mother also explains that they won’t be doing likewise, “Because we never kill anybody.”

The first time Bambi’s mother takes him to the meadow, he is still too young to truly grasp the concept of danger. Still, because it stalks every forest animal, Bambi’s mother tells him urgently to “Run even if something should happen. … Even if you should see me fall to the ground, do not pay any attention to me. Do you understand? … No matter what you see or hear. . . . Just keep going through the forest and run as fast as you possibly can!’” To say that’s a hard promise for a child to keep is an understatement, but it encapsulates the animals’ very real struggle for survival.

Deer top the forest hierarchy, with stags ranked highest of all. The stags largely keep to themselves. It’s considered a special occurrence when the stags appear and engage with others, as with the majestic old prince, who plays a special, paternal role in Bambi’s life.

The animals also see humans, referred to as “He” or “Him.” He and his lethal “third hand” are a matter of forest-wide curiosity and discussion. While there is some disagreement about Him, it’s clear humans signify imminent, life-threatening danger for forest residents. There are no bird watchers here; the only humans these animals ever encounter are hunters.

Death, always lurking, is frequent and ugly. Bambi watches numerous animals, including his friends, suffer painful ends. Lives can be snuffed out by the unforgiving harshness of winter or stronger animals. Others are terminated by Him, whom the animals consider “some dark, inexplicable power holding sway over them.”

Animals’ are unable to ensure their own safety, especially in a world filled with human hunters. On another level, this was also true for European Jews contending with millennia of antisemitism. Writing when he did, there was no way for Salten to know what would befall European Jewry in the 1930s and 1940s. But read in 2022, Bambi feels eerily prescient.

Zipes writes in the introduction to The Original Bambi that on Salten’s father’s side he “came from a distinguished Jewish family, descended from several generations of rabbis.” However, young Salten, the son of an engineer who grew up facing significant antisemitism, devoted himself to assimilating into Viennese society. Over time, though, Salten’s thinking seemingly shifted toward the idea that fellow Austro-Hungarian writer Theodor Herzl had first proposed a few decades earlier: politically organizing to create a modern Jewish state.

Zipes, the translator, emailed that, “During World War I, [Salten] became more interested in Zionism, and it is clear that the problem of antisemitism was on his mind because Jews were blamed for the defeat of the Austrians and Germans and the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. … These were violent times, and Salten was torn—loyalty to Jews or loyalty to Austrian nobility.” Salten had many friends who were members of the nobility, but he also “wrote numerous articles about Jews and antisemitism.”

The novel captures a long-running, intra-communal debate about how to best ensure the survival of a small, frequently persecuted people that never proselytizes. Bambi’s weak cousin Gobo, for example, stands in for European Jews willing to expunge what society believed made them most Jewish. In Salten’s era, this meant Christian conversion, driven not by belief, but a desire to escape antisemitism, advance professionally, and live a more normal life. (A contemporary version: young Jews pressured to denounce Israel, as a prerequisite for acceptance by the left’s so-called Community of the Good.) Notably, this psychological tug-of-war was not abstract; Zipes told me Salten considered Catholic conversion “because it would have made his life easier.”

As for Gobo, the other deer believe he’s dead when he cannot escape hunters they’ve all fled. Gobo is unexpectedly taken home and made a collar-wearing pet. Captivity changes Gobo’s worldview. Upon returning to the forest, Gobo tells the other animals that He is benevolent, and “I don’t need to be afraid of [dogs] anymore. I’m good friends with them now.”

Gobo clearly loses his survival instinct while living with Him: “Gobo never stopped at the edge of the thicket, never looked around for a moment when he walked into the open, but simply ran out without taking precautions.” The old prince openly pities Gobo, who raves about his time in captivity. Bambi is the only other animal who “was ashamed of Gobo without knowing why.” Gobo later runs toward a hunter, only to be shot. Unlike Bambi, Gobo never internalizes the important lessons of survival and self-reliance.

Along similar lines, a hunter’s dog battles a fox to the death in another significant episode. The dog wounds the fox, then refuses to let him die peacefully. The hurt fox summons the energy to taunt the dog as a traitor, turncoat, deserter, and thug: “You miserable creature, you pursue us where He could never find us. You betray us, your own relatives, and I’m almost your own brother! How can you stand there and not be ashamed?” Somewhere deep down, the dog might be ashamed. But that day, he chooses to viciously kill the fox.

The forest is a treacherous place, just as interwar Europe was increasingly menacing. Bambi, seemingly like Salten, learns that a strong survival instinct must be accompanied by self-respect and a willingness to stand apart, perhaps most especially when that’s hard.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.