The well-documented rise of the nones—those who claim no religious belief or affiliation—has fueled theories that politics is taking the place of faith. Even so, some in Generation Z are turning toward the Catholic Church for the tradition and community often lacking in the modern institutions. Harvard University’s 2023 Cooperative Election Study shows a significant increase in just one year in the percentage of millennials and Gen Zers identifying as Catholic—from 16 to 20 percent for millennials and from 15 to 21 percent for Gen Zers from 2022 to 2023.* This unexpected shift suggests that, for some young people, the Catholic Church is filling a void left by modern society.

“I think for those who are already politically on the right, and already have anti-modern disposition, Catholicism can represent something that’s like the beacon of Western civilization, or like that which has stood athwart wokeism all these years, or a living remnant of a more beautiful past,” says Kayla Bartsch, a Yale alumna who converted from Lutheranism to Catholicism in 2021. Bartsch grew up in a conservative family and says the issue of abortion made her more politically minded at a young age. She started going to Mass weekly during her time at Yale, which differentiated her from most of her peers. In light of questions they had for her, she now thinks her classmates were experiencing a vacuum of goodness and truth. The beauty of the faith and tradition drew their curiosity, even if they didn’t agree with Catholic teachings, she now says.

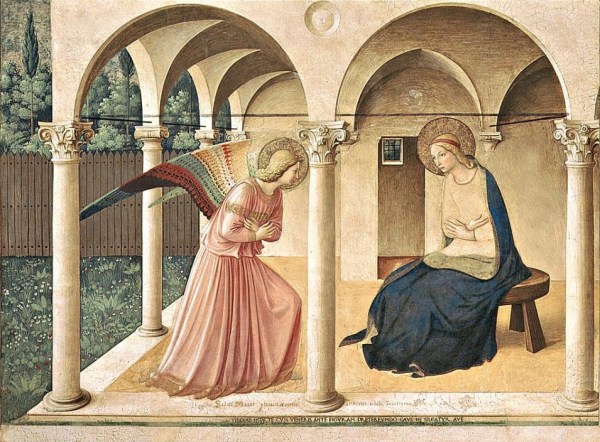

Such cravings sometimes are evident on social media. On TikTok, the trend “Catholic TikTok” features cinematic, high contrast-low light videos depicting the Virgin Mary, rosaries, and orders of priests in traditional robes posted by viewers. The posts tap into a sense of reverence, nostalgia, and mystery that resonates with people seeking something transcendent in their lives. Trends like these make faith relevant in the digital age while attracting young viewers toward tradition.

“I think that it’s an incredible, incredibly powerful tool for evangelization. And so it can and should be used,” Father Simon Teller, a chaplain and Dominican friar at Providence College, a private Catholic institution in Rhode Island, said of social media. Active himself, Teller appeals to his 67,000 followers on Instagram to pray or visit campus events through mostly humorous content. In one post, he relates to the drag that following New Year’s resolutions can be, throwing pens and pencils across the room in his office with a calm voice-over of his “progress.” In another, quick montages of him hosting a pizza party with students, jumping into a pool fully robed, and playing basketball with someone twice his height give a glimpse of his outreach to students on campus.

“I have a lot of experiences of people coming up to me and saying, ‘This drew me into the faith and this led me to this event,’ or ‘This made me think about this differently. Hadn’t thought about it before.’” But, there is a limit. “Social media in general, I think it’s not intrinsically evil, but it’s probably in the long run bad for humanity. And I’m saying this as someone who's very active on social media.” He explains it as a “two-edged sword,” noting its ability to create anonymous spaces where people can discuss religion and morality openly, ideas they might hesitate to express in person because of cancel culture. At the same time, it can confine conversations to echo chambers in which users only engage in dialogue they already agree with, limiting the potential for rigorous intellectual inquiry.

Paige D., a junior at St. Joseph’s University in Philadelphia who asked not to use her full last name, says obsessing over how she came across on platforms like Instagram made her realize how narcissistic she could be. So she began attending events at her campus ministry center. Over time, required theology classes began addressing deeper questions about life and faith and switched her focus from superficial practices to spiritual ones.

“Little things that I once was like, ‘My gosh, I need to spend so much time working on this and making sure my photo looks good.’ Now I’m like, ‘I want to be kind to others and make an impact on the world,’” she told The Dispatch.

The Catholic Church naturally offers a form of community. And heaven itself is described in Catholic teaching as a communion with God: “This perfect life with the Most Holy Trinity — this communion of life and love with the Trinity, with the Virgin Mary, the angels and all the blessed — is called ‘heaven.’ Heaven is the ultimate end and fulfillment of the deepest human longings, the state of supreme, definitive happiness.” (n. 1024). According to a May 2024 Harvard survey, 21 percent of respondents reported experiencing serious loneliness. Among those adults, 67 percent said they were not part of meaningful groups, 61 percent lacked close friends or family, and 65 percent felt fundamentally disconnected from others. Researchers also found that 66 percent of respondents reported a lack of time spent with families contributes to their loneliness.

But family was a key factor for Paige in both leaving the church and returning. Although a “cradle Catholic,” her family stopped going to Mass after she received confirmation.

“My biggest value above all is definitely my family,” she told The Dispatch. “I’m very family oriented along with my faith. I was the one who brought my family back to Sunday Mass because they were the reason I stopped going in the first place.”

According to the same Harvard survey, another major issue facing Gen Zers is a fundamental sense of disconnection from the world. Bartsch, on her search to find meaning, came across the bleak outlook offered by modern philosophers.

“I looked to secular philosophy or psychiatric philosophy, reading through the Western canon to see what others have to say,” she said. “What is a life worth living? And there are a lot of bleak answers, like reading a lot of Nietzsche, reading a lot of Hume doesn’t do great things for personal action.”

Philosophy can lead to some answers, but it fails to fill the longing inscribed on every human heart, the need to connect with others, Bartsch and others would say. Those connections were foundational to her conversion.

“I shouldn’t leave out that a big part of this was just the witness of really devout Catholics in my own life and Christians,” she said. “It was really a two-pronged intellectual journey and relational journey of others in my life who were really wonderful and role models and sort of guided me.”

Invitations and nudges from other Catholics were a common theme among each person interviewed for this piece. Bartsch’s influence from Catholic friends in college nudged her toward the church, but she wanted to do a full intellectual inquiry before becoming Catholic.

“There were a lot of folks who just really talked with me and had long debates about different principles of Catholic teaching and different parts of doctrine that I had issue with and was trying to understand and trying to comprehend,” said Bartsch. That intellectual journey led her to pursue a graduate degree studying philosophy and theology at the Dominican House of Studies, where she regularly had discussions on Thomism and Catholic thought.

Many students end up at religious schools without necessarily being committed to their faith due to scholarships, location, or reputation. Teller says the peer influence and campus culture sparks deeper exploration for some students. Providence College has a student body of about 4,700, and while it is a Catholic school, not all students are active in the church. But, numbers are increasing. This year, 54 students are going through the RCIA program, a preparation process that prepares them for receiving the sacraments of initiation into the Church—baptism, Holy Eucharist, and confirmation.

“The majority are people who hadn’t really thought about their faith until coming here and then maybe seeing friends who go to Mass or meeting with some of the friars, or going to class and hearing their professors talk about religion in a way that they’d never experienced before,” he said. “That often plants a seed making them realize they’ve never taken religion seriously before. And I think a big motive for people is they have an intuition that there’s something real about Catholicism. There’s something real about their faith that they want to be connected to.”

Correction, March 24, 2025: The 2023 Cooperative Election Study showed the percentage of millennials identifying as Catholic jumped from 16 to 20 percent from 2022 to 2023, not 6 percent to 20 percent.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.