President Joe Biden announced last week that his administration would spend more than $42 billion to expand high-speed internet access across the U.S. The White House estimates the program will help over 8.5 million households and small businesses.

It’s the latest effort from the federal government to boost broadband access, and the Biden administration says it can connect every family and small business in all 50 states, U.S. territories, and Washington, D.C., to the internet by 2030.

How will the new program work?

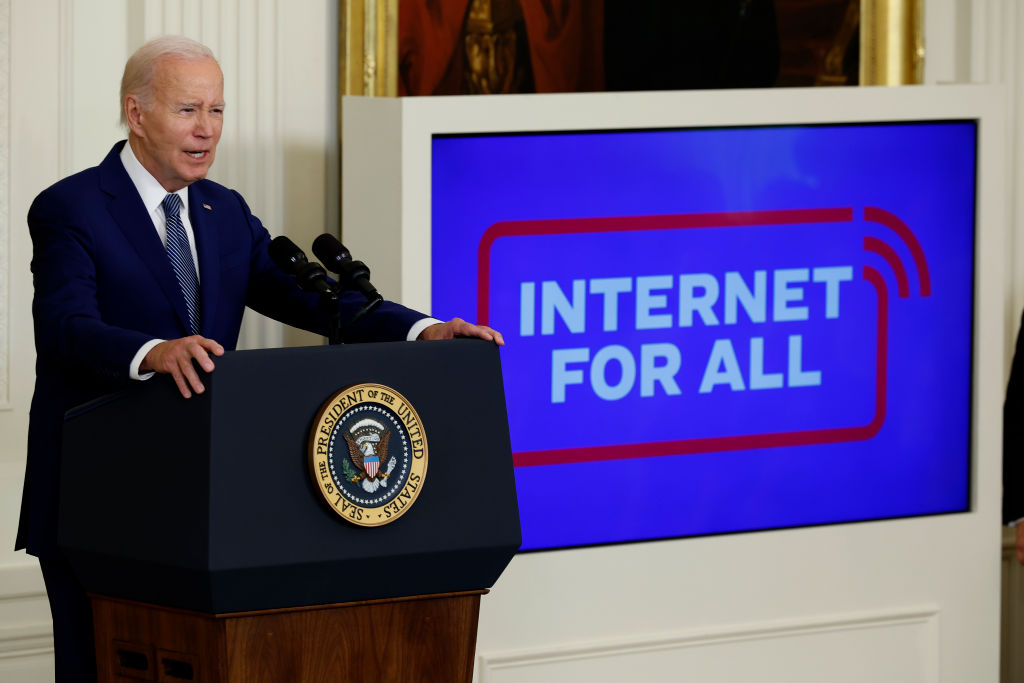

The initiative’s funding comes from the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) program, established by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) that Biden signed in November 2021. BEAD is a major part of the Biden administration’s “Internet for All” initiative.

The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) has spent the last two years developing an implementation program and allotting funding for states and territories based on several factors, such as population size and current broadband availability. Each state, along with Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, will receive over $100 million. Nineteen states will receive more than $1 billion, with Texas receiving the most at $3.3 billion. States are given flexibility on how to spend their allotment—including toward constructing new broadband networks, upgrading existing networks, or passing discounts and vouchers to low-income consumers—pending a proposal approved by the NTIA.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, broadband access has only grown in importance, the Biden administration believes.

“Even if it isn’t your number one issue, it should be your number two issue,” Kevin Taglang, executive editor at the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society, tells The Dispatch. Moreover, broadband infrastructure is critical to extending health services to many rural areas, where hospital closures are prevalent, Taglang observes.

“If you can do telehealth, you can connect people without, you know, having to drive 100 miles to a doctor,” he says.

But others note expanded internet access may not necessarily connect everyone to the internet.

“Internet access is not really the major hindrance for people trying to get connected,” Will Rinehart, a senior research fellow at the Center for Growth and Opportunity, tells The Dispatch. “The biggest impediment to getting everyone connected right now is that there’s a pretty significant trend of people who just don’t think it's relevant.”

The BEAD initiative “went the wrong way,” says Rinehart. “Congress just said ‘okay, here’s a pot of money, it’s gonna be basically $40 billion and just do with it what you will.’”

What challenges does broadband expansion face?

Keeping up with the latest technology is a big challenge for multiyear, tech-focused government programs.

The NTIA intends to utilize fiber optic cables, which are more costly to install but can accommodate upgrades to faster speeds without requiring cable replacements.

“The NTIA was very clear that it expects states to use this money to fund fiber optic networks throughout the country,” says Taglang. “That’s what makes sense—in the long term.”

But fiber optic cables still only last 35-40 years. “So at that point, it’s gonna have to get ripped up and replaced anyway,” Rinehart says.

Maintenance will be another issue. “You spend a whole bunch of money initially in order to get the network in the ground, and then you have to maintain the network,” explains Rinehart. “And a lot of what the BEAD program did is fund that initial getting the networks into the ground.”

To help maintain the network, Taglang points to a separate broadband initiative—the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP), established by the 2021 legislation—that helps connect low-income households to the internet by providing a monthly discount of up to $30 per month.

“One key thing about that program is that it’s going to help with the networks that are built with the BEAD money because it allows for there to be more consumers and more consumers make it easier to support the network’s long term,” Taglang says.

But that $14.2 billion will be gone by next year. “So Congress is going to have to act and put some more money in that kitty so that program can continue.”

Can this model of broadband investment work?

The BEAD project is far from the federal government’s first investment to bridge the digital divide. Apart from the $42 billion Congress allocated in 2021, additional broadband funding authorized in COVID-response bills totals over $50 billion. Even before the pandemic, the federal government was allocating billions toward expansion. And states have invested billions on their own.

“The federal government is very generous when it comes to broadband spending,” Roslyn Layton, a broadband researcher who previously worked with the Federal Communications Commission as part of Donald Trump’s presidential transition team, tells The Dispatch.

Layton thinks one of the biggest problems with past initiatives was the failure to give end users choice in selecting services.

“The best thing we’ve learned is giving vouchers directly to end users,” says Layton, likening it to school-choice vouchers. The valuable component of the smaller ACP program that Congress also funded in 2021 is “the end user gets a voucher and the end user can decide which provider, which technology they want to use.”

When states delegate funding to companies instead of to consumers, state governments hinder efficiency, she says: “A lot of the companies who need the money don't have the resources to apply for—you have to know how to go through the forms, submit them to the right agency.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.