Lots of kids dream of one day being firefighters, astronauts, doctors, or pro athletes. Top White House health adviser Calley Means, it seems, had a different dream.

“From as long as I could remember, I was going to change public policy in the United States,” Means said in a 2023 video interview with the conservative media organization PragerU. “That was my obsession growing up.”

The obsession has become a reality as Means, 39, has gone from being a frequent podcast guest urging a shakeup of the country’s health and nutrition systems to being one of the most powerful and influential health policymakers in the federal government. As a key figure in the Make America Healthy Again movement, he’s part of a vanguard of outsider activists challenging the Washington health establishment. (That movement also includes his sister Casey, a Stanford-educated doctor who quit her residency after becoming disillusioned with the mainstream medical system. She’s now the nominee for U.S. surgeon general.)

But like so many of those empowered by Donald Trump to disrupt the expert class, Means comes from the same world of those he’s looking to supplant: elite universities, a stint in Washington on his résume, and a presumption that the tools of government can solve problems if only placed in the right hands. And right now, incredibly, the health care tools have been placed in Means’ hands.

Perhaps none of this should be a surprise. Means grew up in Washington, the son of a former Nixon and Ford administration aide who later became an executive in the consulting business. After graduating from Stanford and beginning his career working in public affairs consulting—more on that in a bit—the younger Means attended Harvard Business School, graduating with an MBA in 2015. For a few years, Means worked in the Bay Area for a software company before launching a start-up with his wife that sold customized wedding dresses. They sold the startup to David’s Bridal in 2022.

The Means family suffered tragedy in 2021 when their mother, Gayle, died soon after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. In Calley Means’ telling, her death was a moment that “put all the pieces together” for him about the country’s overarching health crisis. In short: The medical, pharmaceutical, and food industries are all incentivized by government and market forces to keep Americans sick.

“We are being lied to that cancer is random, that dementia is random, that kidney disease is random, that all these issues that are killing us are random. They’re not,” Means said in that PragerU video. “They’re all exploding, and they’re all tied, essentially, to food.”

Starting from this dubious and reductive premise, the two siblings embarked on a media- and business-based partnership advancing their belief in alternative medicine. Since quitting her residency, Casey Means opened her own nontraditional medical practice focused on “functional medicine.” (Her medical license in Oregon, where she did her residency, is currently inactive and expires at the end of this year.) Calley, meanwhile, started his own company, TrueMed, that aims to help customers pay for everything from gym memberships to “wellness” products like supplements with pre-tax funds from health savings accounts and flexible savings accounts. They wrote a bestselling book together, Good Energy, that purports to identify the root cause of practically every disease and health condition: bad metabolism.

The pair became frequent guests on television, podcasts, and (most importantly) on Tucker Carlson’s post-Fox News online talk show, offering both personal stories of their encounters with America’s supposedly misguided medical and nutritional establishment and an enticing pitch that the fix for the country’s health problems is a “simple” change in leadership.

To establish his authority on the subject, Means is often introduced as a former D.C.-based lobbyist for some of the companies and industries that benefit from the status quo. (He himself is more careful, usually more accurately referring to himself as working in public affairs.) Much like his sister becoming jaded by the practices of mainstream medicine, Means tells a story about coming to grips with the ugliness of manipulating studies to craft public relations campaigns for the pharmaceutical and beverage industry groups. The subtext of his current activist and policymaking phase is that Means is seeking redemption for all the wrongs he committed during his K Street years.

But others who knew Means from this time in his life—when he worked first at the firm Mercury and later the PR giant Edelman—say he was a relatively junior staffer, working on accounts for the American Beverage Association or Bayer but hardly a decisionmaker on strategy. (Those who knew him then requested anonymity in no small part thanks to Means’ penchant for publicly accusing his critics and opponents of being paid off by corporate interests.) And for whatever misgivings Means has about his time working for these clients, it hasn’t stopped him from boasting on his LinkedIn page that the accounts he worked on “often ran at 40%+ profit margin and highest client satisfaction.” The White House did not return a request for comment.

Regardless of those details, Means tells a good story for podcast audiences looking for confirmation that the powerful are inherently corrupt. In his appearances, Means seems to have answers for questions on issues as divergent as how we treat dementia (poorly) to the approval of weight-loss drugs like Ozempic (he’s against them). Means’ overarching heuristic? If it’s the accepted consensus of the experts, it’s been influenced by bad motives and it’s probably wrong. “We need to break free from the incentives of a medical and food system that is highly incentivized for us to be addicted to cheap and dangerous food, and sicker for longer periods of time,” he said in the PragerU video. “We need to listen to ourselves, do our own research, and not listen to the experts.”

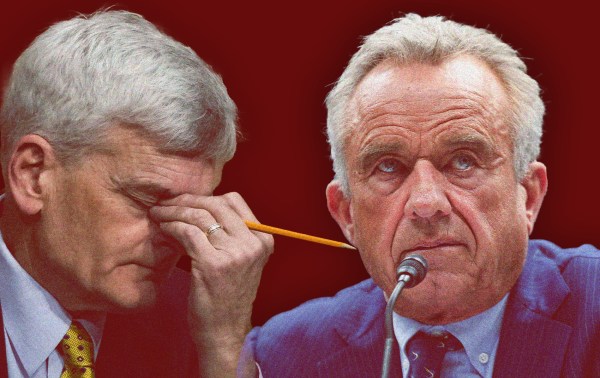

Thanks to February 2024 appearance with Carlson, Means caught the attention of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. The two met soon after at an event for Kennedy’s presidential campaign in Austin. Means would later reveal on another podcast—Joe Rogan’s, of course—of what transpired in the portable sauna where he and Kennedy sat and talked. “Actually, it sounds very woo-woo, but I was in a sweat tent with him in Austin at a campaign event,” Means said. “I just had this strong vision of him standing with Trump and how what RFK represents is actually what Trump represents.”

Means became close with Kennedy, advising him on his campaign and later brokering the meeting between him and Trump that led to the Democrat-turned-independent dropping out of the race and endorsing the Republican nominee. Means was suddenly a major political player, helping forge an alliance between MAGA and MAHA that may have helped deliver the White House to Trump.

Means officially joined the administration as a White House health adviser in March, and it’s clear his viewpoint holds a lot of sway in Trump’s Washington.

On another episode of Carlson’s online show last year, the former Fox News host asked Means what he would do if he were president. “Day one: state of emergency for childhood chronic disease,” Means said. “What’s happening in childhood chronic disease is a much-orders-of-magnitude bigger state of emergency right now and more imminent emergency in America than COVID.”

It didn’t happen on day one exactly, but it sounds awfully similar to what President Trump established through an executive order in February: a commission, headed by Kennedy, charged with “investigating and addressing the root causes of America’s escalating health crisis, with an initial focus on childhood chronic diseases.”

Means didn’t just inspire the commission; by all accounts, he was deeply involved in its recently released, 72-page “Make Our Children Healthy Again” assessment. The report lays out a case for what is causing chronic diseases in children, targeting everything from processed foods and pesticides to overmedication and overexposure to screens. (But as NOTUS reported this week, the report has some issues, including the fact that several of the academic studies cited in footnotes don’t seem to, erm, exist.)

But the throughline of the report is also a throughline in Means’ own thinking: America’s health is being held hostage by the profit motive of the pharmaceutical and food and beverage industries, which not only lobby the federal government to protect their interests but infiltrate the institutions of society to reinforce their market position.

“Let’s not get conspiratorial,” Means said during an appearance last year on the Skinny Confidential podcast. “Let’s just be very specific: The food industry wants our food to be addictive and cheap, and the health care industry, just as a statement of economic fact, they want people to be sicker for longer periods of time.”

But while Means has quickly ascended by performing as an insider uncovering the sinister motivations of his one-time peers, he also tries to work the system to his benefit. It was just last year that Means was heading up his own united coalition called End Chronic Disease that included the leaders of companies like exercise brand CrossFit and health supplement company AG1. This lobbying effort aimed to push back on the IRS crackdown on people using their pre-tax health care dollars to buy these products, a direct threat to Means’ company TrueMed.

Meanwhile, one of his company’s competitors in the wellness space has filed an ethics complaint against Means. The complaint alleges that Means has used his position in the Trump administration to threaten the CEO of the Wellness Company, Peter Gillooly, after he accused Gillooly of leaking false information about TrueMed.

“If one more thing happens, I’m going to go to [National Institutes of Health director] Jay Bhattacharya and Bobby [Kennedy] and tell him that you and your cadre … are spreading lies and trying to f— with him and hurt his administration,” Means said in a phone call with Gillooly, who says Means’ actions represent a conflict of interest. Means has pushed back, telling Politico he was merely threatening legal action against someone he believed to be spreading false information about his company.

Lobbying for special favors, vague lawsuit threats, a fight spilling out in Washington’s premier trade publication—there’s no doubt that Means remains an insider, through and through.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.