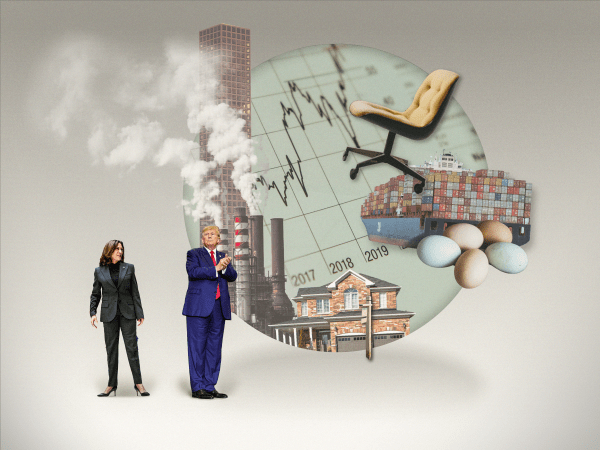

Editor’s Note: Although partisans on both sides of the aisle have warned that the stakes of the upcoming presidential election could not be higher, the two campaigns themselves have been remarkably light on policy substance. With Election Day now a week away, we reached out to dozens of thinkers, writers, and analysts and asked them about their biggest concerns about a potential Trump or Harris administration.

Our final entry focuses on the rule of law and governing norms, including topics ranging from court packing, religious liberty, and the peaceful transfer of power.

Harris or Trump could imperil the peaceful transfer of power.

“Presidential power,” declared presidential historian Richard Neustadt, “is the power to persuade.” By virtue of being the center of attention, a president can move the minds of Congress and the public.

A party’s presidential nominee has similar power. He or she has been the center of a massive campaign that has involved raising and spending billions of dollars and mobilizing untold volunteers. The candidates are the heads of pop-up cults promising fervid supporters to lead them to the promised land or prevent the other candidate from taking the country to hell.

Only one candidate can be president, which places the onus on the losing candidate to admit defeat and tell their supporters to accept the results. On January 6, 2020, we saw the peril posed by a sore loser.

Both Kamala Harris or Donald Trump could foment an even worse scene this January. Imagine the House of Representatives once again has a thin majority, and when it comes to the Capitol to open the session an aggrieved rump of legislators decides to keep fighting at the behest of their narrowly defeated presidential candidate. They refuse to support their party’s candidate for the speakership. It is the Kevin McCarthy scenario all over again, and it stops the House from coming to order and entering a joint session with the Senate to count the states’ electoral slates and announce the winner of the presidency. The legislative and executive branches are frozen, and the government’s funding lapses.

Character matters. Self-government cannot survive without it.

Kevin R. Kosar (@kevinrkosar) is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and edits UnderstandingCongress.org.

Regardless of the outcome, polarization seems poised to worsen.

In my last book, I described what I call the “two-party doom loop”—a vicious cycle of escalating rhetoric and increasingly intense elections. As parties become more polarized, they compromise less and demonize more. It only gets worse and worse.

Unfortunately, the two-party doom loop of intensifying hyperpartisan polarization remains on a runaway downslide toward democratic breakdown. It shows no signs of slowing regardless of next week’s outcome.

Whether Vice President Harris or former President Donald Trump wins the presidential election, their victory will be narrow, uncertain, and excessively litigated. A narrow victory following a certain deluge of legal challenges will offer no clear mandate. Instead, it will supply plenty of reasons for the losing side to think it both could have and should have won.

If Harris wins, Trump will not go lightly. He has already foreshadowed his 2024 stolen election claims, leaving little to no hope that he will let go. He will almost certainly demand his supporters in Congress and state legislatures challenge the election. Denialism has become the platform of the Trump GOP, and noncitizen voting is the prefabricated excuse. I worry this conflict will only get worse. Republican officeholders will face intense pressure to remain hostile to a Harris administration, hoping to sink it from the start.

If Trump wins, Democrats may concede, but they would only sharpen their attacks on Trump and likely use their control of many state governments to object to and obstruct Trump administration policies on a range of issues, from immigration to policing to climate policy. If that happens, Trump would welcome the conflict. He has telegraphed a combative, vindictive administration that will pursue aggressive lawfare. Democrats will more than feel justified in fighting back. They will see it as a political and moral necessity.

Could anything break this escalation? The logic of the doom loop is that retaliation demands retaliation. Shared opposition is a unifying force in a binary conflict. As long as the conflict remains binary, and the two sides remain roughly evenly balanced, both sides can contemplate a future of total victory. This is a dangerous illusion, and the doom loop will not resolve on its own. Without significant changes to our electoral and party system—such as proportional representation and fusion voting—it will continue until American democracy breaks apart.

Lee Drutman is the author of Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America and a senior fellow at the New America.

Could Trump openly defy a Supreme Court decision?

Like most libertarians, I typically see little difference between the major parties’ respective presidential candidates. Red or blue, he or she will expand government, increase the debt, pick fights abroad, and generally flout the Constitution’s allocation of power.

Yet this cycle, Donald Trump seems to me to be categorically worse because of his mix of narcissism and disdain for norms. Simply put, Trump sees everything through the lens of how it affects or reflects upon him, and he values—or denigrates—institutions, customs, and people accordingly.

I share others’ concerns about the many ways Trump might abuse the powers of that office in a second term, including weaponizing the Department of Justice against political opponents; deploying troops to suppress dissent under the Insurrection Act; and even refusing to step down at the end of his term on one pretext or another. But another scenario has received less attention than I think it merits: the possibility of President Trump openly defying a decision of the U.S. Supreme Court.

The judiciary famously lacks the power of the purse or the sword. Its ability to serve as the final arbiter of disputes over constitutional limits on government flows entirely from the acquiescence of political actors who obey those decisions as a matter of custom, not compulsion. I see three reasons to fear that Donald Trump might well be the first president to explicitly repudiate that norm.

First, Trump’s recent experiences as a civil and criminal defendant have likely solidified his view that the legal system is a fundamentally rotten institution with no more authority or legitimacy than some zoning board standing between him and his latest real-estate development project. Second, Trump would be a lame-duck POTUS with good reason to believe he can—again—win a game of impeachment-chicken with Congress. It’s reasonable for him to suppose there would be no practical consequences if he tells Chief Justice John Roberts and company to pound sand.

Finally, Trump learned two important lessons from his first administration and particularly from January 6: the importance of surrounding himself with conniving rogues who value their own political ambitions more than the Constitution, and just how many there are to choose from in this town.

Clark Neily is senior vice president for legal studies at the Cato Institute.

The new president will inherit a new religious liberty legal landscape.

The relationship between religious liberty and federal regulatory power will be a key issue for America’s 47th president, whoever it is.

The new chief executive will be operating in a new regulatory environment—one where, after the Supreme Court’s Loper Bright decision, federal agencies can no longer have the final say on what the law means. The law of religious liberty could be greatly improved by the executive embracing that principle. That’s because most religious liberty cases at the Supreme Court over the past 15 years do not involve democratically enacted legislation, but regulatory action.

When courts gave regulators binding deference on what the law meant, numerous burdens on religious liberty followed. I discuss two notable ones in this brief I filed with my Becket Fund colleagues in Loper Bright. One involves the continued effort to force the Little Sisters of the Poor to violate their religious teachings and pay for insurance coverage of contraceptives and abortifacients. The other involves the federal government attempting to force doctors to attempt surgical gender transitions. In both instances, federal regulators went well beyond the statute at issue, and that regulatory abandonment enabled religious conflicts. Such obvious conflicts could be avoided by a future administration that grapples with the Supreme Court’s efforts to limit otherwise unchecked regulatory discretion.

As the brief explains, one way the next president could minimize religious liberty conflicts in a deference-free environment would be to direct federal agencies that burdening the free exercise of religion can be a “major question.” That means, when the proposed regulations burden religious exercise, agencies must either point to history and context evincing clear congressional authorization before the regulations can proceed or they must grant sufficient religious exemptions to avoid burdening religion.

This would be an important complement to federal religious liberty protections that agencies must also obey. It could minimize the time a new administration spends defending its religious burdens in court—because it will be the Constitution, not changing regulatory whims, that guarantees free exercise.

William J. Haun is senior counsel at the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty and a nonresident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

For a Harris administration, embracing court packing would defy constitutional norms.

Like many ideas that were once on the radical fringe, court packing now has an air of inevitability if Democrats can just manage to win enough seats in Congress (and, of course, the White House). A newly ascendant Democratic Party, we are increasingly told, cannot abide an independent branch of government whose members had been appointed by its vanquished foe. As a presidential candidate in 2020, Kamala Harris embraced the idea, and she has not done much to distance herself from it since.

We heard a great deal about the sanctity of constitutional norms during the Trump presidency, but that was then and this is now. The independence of the federal judiciary is ultimately a matter of constitutional norms, and there are myriad ways to undermine the independence of the courts if one has the political will to do so.

The Constitution says that judges hold office during good behavior, but some of those now advocating for “judicial reform” posit that this constitutional guarantee means only that judges are entitled to their salary. So long as they keep their government paycheck, they might be stripped of their public duties and their powers and responsibilities exercised by newly appointed judges.

Court-packing advocates could also simply dilute the justices’ votes by adding more. The Constitution says that there will be one Supreme Court, but it leaves the organization of that court to Congress to perform by statute. The Constitution doesn’t specify how many seats the Supreme Court must have, and Congress has historically filled in the gap. Over the first decades of the 19th century, the court grew as the justices’ workload increased, eventually stabilizing after the Civil War at its current size of nine justices. Congress could by statute add new seats to the court.

But this is where constitutional norms supplement the constitutional text. The judiciary is only independent of the legislature if Congress refrains from tampering with it. If, on the other hand, Congress responds to judicial decisions that it does not like by adding seats to the court and appointing more pliant justices to reverse those decisions, then the independent judiciary has form but no substance. It would mean that if Congress does not like the constitutional law as interpreted by the court, it can in effect rewrite constitutional law by adding the necessary votes to the court.

Then-governor and future chief justice Charles Evans Hughes once said the Constitution is what the judges say it is. He meant it as a warning. The judicial safeguard of constitutional limits on government power would endure only so long as politicians refrained from eroding it. Some are eager to do away with it. When norms fade, it is just a matter of who gets to exercise power.

Keith E. Whittington is David Boies professor of law and director of the Center for Academic Freedom and Free Speech at Yale Law School.

Trump looks for sycophants while Harris floats unserious election reform.

On July 30, 2020, when it was becoming clear he might be voted out of office, then-President Donald Trump floated the idea of not holding the November election at all in favor of some vaguely specified “delay.” That idea went nowhere.

Less than six months later, after he had attempted to instruct the Department of Justice to announce falsely that it had found voting irregularities, Trump and advisers contemplated sending in federal troops to seize voting machines—and perhaps rerun the election in contested states—invoking the Insurrection Act, and even declaring martial law. He held back from doing those things, at least in some cases because aides warned him that the courts would rule against him and that they would resign en masse, a step likely to galvanize public opinion.

My chief concern for a second Trump term is that he will fill the Justice, Homeland Security, and Defense departments with subordinates who will not try to keep him within the bounds of the law. His own running mate, Sen. J.D. Vance, suggested in 2022 that Trump should “fire every single midlevel bureaucrat, every civil servant in the administrative state, replace them with our people. And when the courts stop you, stand before the country, and say ‘The chief justice has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it.’”

Last time the guardrails held; I do not count on them holding again.

A potential Harris administration also has me worried about the future of elections—and about whether Harris’ advisers even understand the stakes. The misnamed Freedom to Vote Act, endorsed by Harris, is the latest version of a shambling omnibus bill of centralizing ideas on voting, many at odds with constitutional guarantees of speech and association, and baldly partisan to boot. Bizarrely, it doesn’t address many of the genuine electoral perils of the Trump era, being instead a wish list of election reforms progressive groups have been flogging since well before 2016. Even on gerrymandering—for which there’s a case for federal reform—it’s an awful botch, tying states up in abstruse expert formulas while actively discouraging traditional criteria of good districting.

Most frustratingly is that adherence to the Constitution and the democratic process are supposed to be the Democrats’ great edge against Trump—and their biggest opportunity to forge a cross-ideological consensus with level-headed Republicans. To come out with a coercive, kludgey contraption is a wasted opportunity.

Walter Olson is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute’s Robert A. Levy Center for Constitutional Studies.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.