On December 16, 2024, then President-elect Donald Trump sounded an optimistic note on America’s future with the People’s Republic of China (PRC): “China and the United States can together solve all of the world’s problems.” Four months later, according to reporting from the Wall Street Journal, the president met with Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent to discuss ways to “isolate the Chinese economy.” The key intervening event was, of course, the trade war that Trump launched on April 2.

These events are a Rorschach test. The president’s most ardent supporters perceive a coherent plan to strategically decouple from the PRC at a global scale, and on trade and tech, they have a point. The administration has prohibited companies like Nvidia from selling modified semiconductors to China. Trump has closed loopholes that allowed fast-fashion giants Temu and Shein to evade tariffs and import slave labor-produced goods into America. Most recently, the president approved sweeping export controls on Huawei-produced chips.

But those supporters miss something more fundamental happening in America’s relationship with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). In the domains that arguably matter most to the party—ideology and information—the United States is unilaterally surrendering. Even worse, Washington is effectively doing the CCP’s work for it. At its core, though, this problem is not one of Trump or former President Joe Biden, nor one of any political party. America is stuck in self-defeating strategic behavior—rooted in a deep-seated preexisting condition: a refusal to believe in trade-offs.

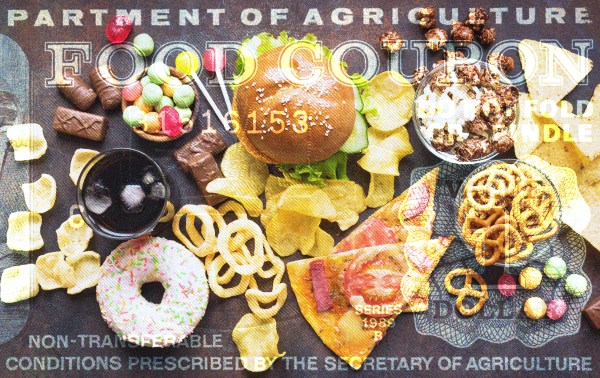

The cult of American prosperity.

When America won the Cold War without firing a shot, Washington celebrated its success by drawing all the wrong lessons from victory. Consider President Bill Clinton’s stunning declaration in 1994 that “our goals of enhancing our security, bolstering our economic prosperity, and promoting democracy are mutually supportive.” Why? Because “nations with growing economies and strong trade ties are more likely to feel secure and to work toward freedom.” Clinton’s words echoed George H.W. Bush’s 1990 proclamation of a “new world order” wherein “the rule of law supplants the rule of the jungle.”

This naive triumphalism was rooted in the belief that the United States of America is lucky enough to live without trade-offs. Twentieth-century theologian Reinhold Niebuhr dubbed this malady “the American cult of prosperity” that seeks the “amelioration of social tensions through constantly expanding production.” Andy Crouch, a contemporary public intellectual, warns about technology as a kind of dark alchemy that promises “abundance without dependence.” And in the early days of the Cold War, Niebhur cautioned his fellow Americans against believing in that alchemy: “Expansion cannot go on forever and ultimately we must face some vexatious issues.”

We face another such moment today. Americans have benefitted handsomely from welcoming the PRC into the global economy in the form of abundant consumer goods readily available at cheap prices. China is also a top market for U.S. businesses, and Beijing’s investments in U.S. treasury securities have helped drive interest rates down in America. This arrangement has also rebounded to Beijing’s benefit by providing reliable markets for its production-led economy. Ten years before Trump declared that Washington and Beijing could solve the world’s problems, then-President Barack Obama said as much. Standing next to Xi Jinping in the White House Rose Garden, Obama heralded what he saw as a symbiotic relationship: “As we work to narrow our differences, we can continue to advance our mutual interests for the benefit not only of our two peoples, but for the benefit of the world.”

This hope has not materialized. Instead, engaging China economically has strengthened the CCP politically. The party has leveraged this power not to liberalize its politics but to threaten America’s institutions. The cult of American prosperity promised a different outcome, one where wealth would pacify the CCP while enriching U.S. citizens and corporations. Instead, Beijing has leveraged our money and technology to bend U.S. companies to their will, steal their intellectual property, and threaten our economy with sabotage.

Our own hands have built the monster we now confront. The American cult of prosperity is founded on the lie that prosperity is more potent than conviction. The CCP’s theory is the exact opposite: ideas are paramount, because they are the party’s greatest weakness.

Battlefield of ideas.

In 2013, Washington was embroiled in debates about health care. Six thousand miles away, the CCP was fixated on ideology. While the Arab Spring revolutions overtook the Middle East, Xi Jinping was consolidating his rule in Beijing. Looking to the chaos of “color revolutions,” Xi and the CCP elite emphasized the danger of immaterial threats to the party’s authoritarian rule over China. In a widely circulated communique colloquially referred to as “Document 9,” the CCP’s top leaders warned of an “intense struggle” over ideology. The document identifies Western notions about constitutional democracy, human rights, civil society, free markets, and freedom of the press as vital threats that “undermine the CCP’s historical purpose” and challenge “the legitimacy of the CCP’s long-term political dominance.”

The communique specifically warned against “media operations and [non-governmental organizations] operating inside China.” Though unnamed, Beijing was likely referring to organizations like the National Endowment of Democracy (NED) and Radio Free Asia (RFA), both of which have actively worked to foster freedom of expression in China. But Document 9’s conclusion, however, contained a more implicit directive—to “strengthen guidance of public opinion on the Internet [and] purify the environment of public opinion on the Internet.”

What this means is that Document 9’s stated “intense struggle” over ideology would not stop at Chinese borders. As the Jamestown Foundation’s President Peter Mattis has observed, the CCP defines national security not as threat mitigation, but threat elimination. This expansive concept of security compels Beijing to go abroad in search of monsters to destroy. In 2021, Xi identified one such monster: foreign perception of the CCP. As Xi put it during a meeting of the Politburo, Beijing needed to control “external discourse mechanisms” over specific foreign audiences to “make friends, unite and win the majority, and constantly expand our circle of friends who know China and are China-friendly.”

Xi didn’t mention TikTok, but Chinese state media did so in subsequent coverage in 2021. Four years later, we are beginning to understand how Beijing wields TikTok as a weapon of psychological warfare. A recent investigation into TikTok’s algorithm from the Network Contagion Research Institute at Rutgers University revealed evidence of “scaled indoctrination” on TikTok: more time spent on the app correlates with a more favorable perception of the CCP among U.S. users.

Reading between the lines, one recognizes the CCP’s gambit from as far back as 2013 to flip the ideological domain from a liability into an advantage. Judging by recent events, Beijing has largely succeeded, and America has no one to blame but itself.

Unilateral surrender.

Thirty-five days after declaring on December 16 that Washington and Beijing could effect world peace, Trump signed Executive Order 14166, which illegally paused the enforcement of the Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary Controlled Applications Act, passed the previous summer during the Biden presidency. As Trump put it, he had developed a “soft spot in my heart” for TikTok and no longer viewed the app as a national security threat.

Trump’s pivot soothed the U.S.-China relationship, but it also left in place Beijing’s most potent ideological weapon on the phones of 135 million Americans. That’s a bad deal for the United States. In the wake of Hamas’ terrorist attacks against Israel on October 7, 2023, pro-Palestinian content outnumbered pro-Israel content by a margin of 4 to 1. In November 2023, the late Osama bin Laden’s “Letter to America” went viral on TikTok, with many young Americans expressing sympathy with the mastermind behind the September 11 terrorist attacks. More recently, TikTok artificially boosted content from Chinese manufacturers to induce sympathy among U.S. users for the Chinese victims of Trump’s trade war with Beijing. Nevertheless, the Trump administration persists in preserving the CCP’s ability to wield this weapon of mass disinformation.

Trump also signed an executive order on January 20 that mandated a 90-day pause on all foreign assistance, pending a review—impacting funding for NED and countless NGOs whose ideals are opposed to those of the CCP. The administration’s argument to justify this step was alarming: “The United States foreign aid industry and bureaucracy … destabilize world peace by promoting ideas in foreign countries that are directly inverse to harmonious and stable relations to and among countries.” The word “harmonious” echoes the CCP’s own propaganda about “harmonious development,” “peaceful coexistence,” and “a common destiny for all mankind.” Even more troubling is the administration’s misguided war against NED; indeed, in February, Elon Musk made arguments against the organization that were literally lifted from Chinese state media.

The following month, the administration announced that the U.S. Agency for Global Media—and, by extension, RFA—was “unnecessary” and announced their effective defunding. The CCP wasted little time in dancing on RFA’s grave.

These failures are not unique to Donald Trump or the Republican Party. The Biden administration actively lobbied against the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act in 2021, covered up the FBI’s investigation into China’s “spy balloon” after it attempted to conceal the balloon’s presence from the American public, and scrubbed references to CCP “malign influence” from State Department documents—all to set favorable conditions for high-level diplomacy that never actually yielded concrete outcomes. That was the fatal conceit that crippled the prior administration: avoiding conflict requires managing competition, even at the cost of ignoring the CCP’s true nature.

Nor are these shortcomings unique to government. In May 2025, YouTube influencer Drew Binsky visited Xinjiang and recorded his visit in a region of an ongoing genocide without mentioning the atrocity a single time. He is the latest in a long line of millennial and Gen-Z “useful idiots” who advance the party’s propaganda. American corporations are also implicated here: Consider the consulting giant McKinsey & Company, which was involved in crafting a report that advised the CCP on how to boost its technological and industrial capabilities—in direct competition with the United States. (Though McKinsey denies involvement.) Microsoft, for its part, provided critical training that contributed directly to the CCP’s surveillance state. In each of these examples, America’s prosperity cult contradicts its ideological creed. The CCP is exploiting this dissonance to gain ground in the battlefield of ideas.

Leaving the cult.

There is no cost-free path to addressing the China challenge. Shutting down TikTok would eliminate a powerful political messaging platform for Trump. Recognizing the inherent value of organizations like NED and RFA complicates domestic narratives. The cult of American prosperity, taken to an extreme, promises a false gospel: no trade-off exists between economic self-interest and the national interest. That heresy is crippling America’s ability to challenge the CCP in the domain of ideas, the very terrain where the party is most vulnerable.

Nothing worthwhile in this life is free. That simple truth is, as Christ put it in his own day, “a stumbling block” and “a rock of offense” to political elites. Embracing it, however, is the beginning of America’s path to recovery. Difficult as they are, preexisting conditions are often manageable. America needs a dose of reality. If we refuse this medication, others who do not prize our best interests will force poison upon us, and we will lack recourse to refuse it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.