If you listen to how Republicans in Washington talk about federal spending these days, you might imagine that we have entered an era of budget restraint.

“Fiscal responsibility is what we do as conservatives,” House Speaker Mike Johnson said in February. “And we have a $36 trillion federal debt. We have a giant deficit that we’re contending with. I think we need to pay down the credit card.” President Donald Trump has said much the same, suggesting that his administration aims to balance the federal budget before his term is out. Elon Musk has called the growth of federal debt “terrifying,” and said “if this continues, the country will go, become de facto bankrupt.” All of them, and many other Republicans in D.C., have argued that this is why the administration and Congress have made fiscal reform a priority, and why it’s worth doing despite the political cost.

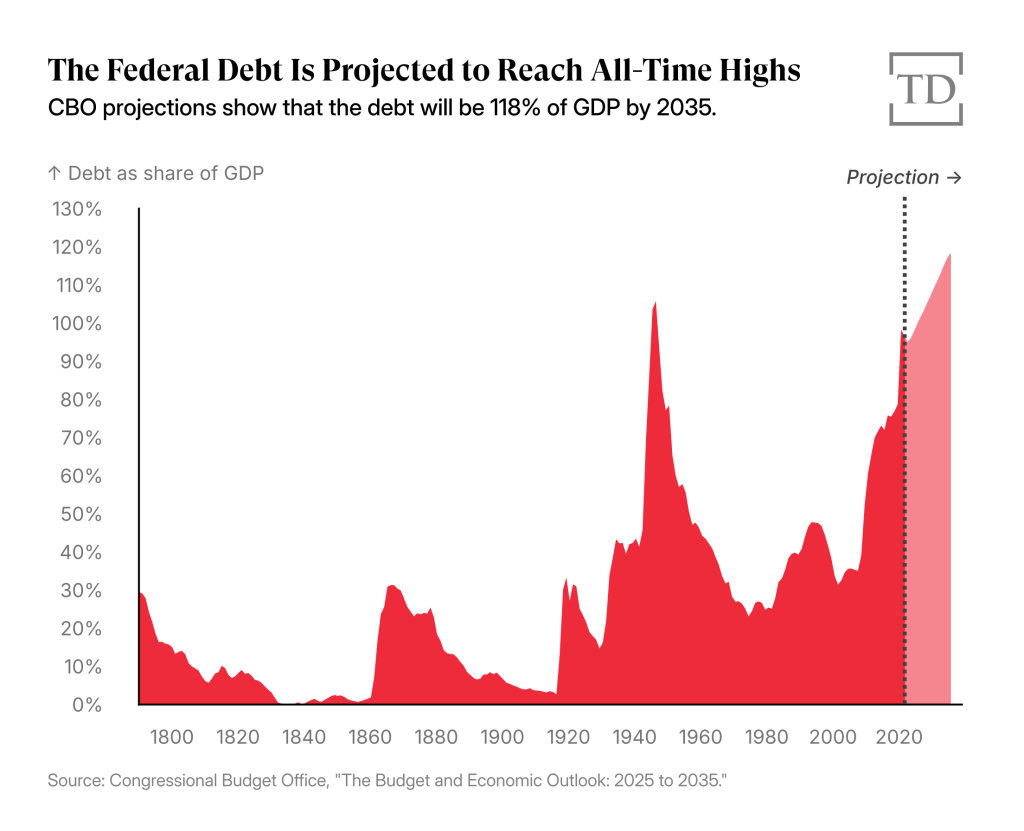

There certainly is reason to worry. Johnson is quite right that the federal debt now exceeds $36 trillion, which is about the size of the entire U.S. economy and therefore a scope of debt not seen since World War II. That debt is only slated to grow, and debt payment itself is an increasing burden on the economy—with annual interest costs rising to nearly $1 trillion this year (about three times what they were just five years ago).

But although Republicans’ concerns about the debt are well grounded, their claims to have picked up the mantle of reform in response are baffling. The notion that Donald Trump’s second presidency has launched an era of austerity and budget cutting is widespread among Republican politicians. They point to the aggressive slashing of government by the so-called Department of Government Efficiency, to the shuttering of some agencies, and to intense negotiations to curb spending in the reconciliation bill now being hashed out among congressional Republicans. They note that Democrats are accusing them of strangling the government, and describe a commitment to bear heavy political costs for the sake of the nation’s fiscal future. Many congressional Republicans, and many Republican voters, seem genuinely to believe that we are in an era of deficit reduction.

But we are not. All the brash talk about DOGE slashing spending has been adding up to very little. The tax and spending proposals that Republicans are crafting this spring are in fact recklessly profligate. And no one dares to touch the entitlement programs that are the actual chief sources of the government’s fiscal challenges.

Republicans are in the process of ballooning the debt, and at times they seem not only unwilling to acknowledge it but even genuinely unaware of it.

The Trump administration’s first 100 days were dominated by the spectacle of DOGE. Unofficially run by Elon Musk, it took on several related tasks. It made a hard push to force some federal bureaucrats out of their jobs, and those changes could well endure. It has also tried to modernize some federal computer systems, where presumably it is well equipped to succeed. It has tried to force a restructuring of several federal agencies, which may not survive court challenges yet could still leave a lasting mark. But at the center of its mission has been the elimination of wasteful spending, and on that front the story of DOGE has been a farce.

Musk came in claiming his people could cut $2 trillion out of the budget, or nearly a quarter of federal spending. He brushed off questions about just how that could be achieved with vague intimations of immense secret pots of corrupt and wasteful spending. At first, he could sustain this by pointing to various ridiculous uses of public dollars in assorted agencies, but none of it added up to anything like the savings he had promised.

By March 27, when Musk and several DOGE leaders sat down with Fox News’ Bret Baier to talk about their work, his ambition had been cut in half. “Our goal is to reduce the deficit by a trillion dollars,” he told Baier,

So from a nominal deficit of $2 trillion to try to cut the deficit in half to $1 trillion, or looked at in total federal spending, to drop federal spending from $7 trillion to $6 trillion. We want to reduce the spending, by eliminating waste and fraud, to reduce spending by 15 percent, which seems really quite achievable. The government is not efficient, and there is a lot of waste and fraud, so we feel confident that a 15 percent reduction can be done without affecting any of the critical government services.

Just two weeks later, Musk had scaled down his expectations dramatically, announcing at a Cabinet meeting that he expected DOGE to reduce federal spending by $150 billion this year.

But even having reduced his projection of potential savings by more than 90 percent, Musk still appears to be exaggerating what DOGE has achieved. As of early May, about $70 billion in cuts have been itemized on DOGE’s website, and even some of those will not actually reduce federal spending unless Congress rescinds them from this year’s appropriations statutes. That figure also does not account for the costs involved in firing and rehiring workers, providing severance and paid leave, lost productivity, diminished tax enforcement, and other implications of DOGE’s personnel moves.

On net, as the Manhattan Institute’s Jessica Riedl has noted, it is entirely possible that DOGE will actually increase federal spending for the year by a bit. But even if it meets its much-diminished claims, its effects on the government’s fiscal trajectory will be marginal. Every bit counts, and $70 billion is real money. But it is less than 1 percent of federal spending for the year.

At this point, no one can claim that DOGE will be a budgetary game-changer.

The actual federal budget process stands to make a bigger difference, but in the wrong direction. Congressional Republicans are at work on a reconciliation bill aimed at extending the tax rates established in 2017. In that process, budget hawks are working to contain the fiscal damage, but there is no reason to believe such damage will be altogether averted, or even kept particularly modest. That bill looks very likely to significantly accelerate the growth of the debt.

As written, the budget resolution that House and Senate Republicans adopted in April (which established the general parameters of the ultimate reconciliation bill) is almost unthinkably irresponsible. It gives Congress the room to reduce federal revenues by more than $5 trillion and increase spending on net by about $500 billion over the coming decade. Republicans almost certainly won’t balloon the deficit by quite that much. But by giving themselves the room to do it while promising not to, they’ve demonstrated their perception of the dynamics of today’s fiscal politics. Increasing deficits is easy, shrinking them is hard, and Republicans think they can do the easy thing first to keep the legislative process moving and do the hard thing later when they’re under time pressure to get a bill done. That is not exactly an encouraging outlook.

Just continuing existing tax policy would drive the federal debt well beyond 200 percent of the size of the economy over the next 30 years, according to the Congressional Budget Office. By that point, interest on the debt would take up about 80 percent of federal revenues. Such levels of borrowing present enormous risks to the American economy, and even in the absence of any dramatic fiscal crisis would reduce growth significantly. And Republicans are likely to increase the deficit by more than that, because they are looking to cut taxes further than they did in 2017, and to increase spending on defense, immigration enforcement, and a number of other priorities.

The idea that this is what legislators are doing might come as a surprise to anyone observing Congress over the past month, since congressional Republicans are spending all their time fighting bitterly about the scope of spending cuts in the reconciliation bill. But these cuts are offsets of revenue reductions and spending increases that will add up to much more debt on net.

To avoid fully confronting that reality, some Senate Republicans have sought to mask the cost of extending the lower tax rates adopted in 2017. When those rates were enacted, they were set to expire this year, in order to keep the 10-year cost of the tax bill more presentable. So the CBO’s formal budget projections have assumed those rates will disappear next year. If Congress extends them for another 10 years instead, its usual method of projecting costs (the so-called “current law baseline”) would require treating the extension as adding several trillion dollars to the deficit. But Senate Republicans are instead proposing to use not the law now on the books for the coming years but the policy in effect for this year—with the 2017 tax-cut rates still in place—as the baseline for the budget. Under such a “current policy baseline,” extending these tax rates would be said to create no new cost.

In effect, then, the increased deficits that will result from lower revenue in the coming years were not counted when the reduced tax rates first went into effect in 2017 (because everyone pretended they would end this year), and will not be counted if they are renewed this year (because everyone will pretend they were never supposed to end). They just won’t be counted at all. Congress will increase the deficit by almost $4 trillion over the next 10 years but not account for that increase in its budget math. That wouldn’t be a way of reducing the cost of the reconciliation bill, it would just be a way of ignoring its cost. And even that gimmick wouldn’t be enough to let Republicans claim they were reducing the debt.

The fact is that the only major legislative aim Republicans are pursuing this year will significantly increase future deficits and debt. And the effort to offset at least some of those costs is leading congressional Republicans into epic battles over spending that cast serious doubts about their ability to advance more fiscally responsible budget measures in the coming years.

The Trump administration’s budget proposal for next year, which was released May 2, highlights the nature of this challenge. The administration proposes reductions of almost 25 percent in non-defense discretionary spending, but would leave Social Security and Medicare essentially untouched. This was the administration’s approach to budgeting in Trump’s first presidency too. And it failed on several fronts. Because Congress cannot take such a budget seriously, it effectively surrenders the president’s first-mover advantage in the annual appropriations process. But because the budget process allows its supporters in Congress and the public to talk about bold spending cuts while not actually offering a path to controlling the growth of the debt, it encourages a culture of self-deception about fiscal policy.

The president’s budget thus encapsulates the story of contemporary fiscal policy: lots of talk about painful cuts while the debt continues to accelerate.

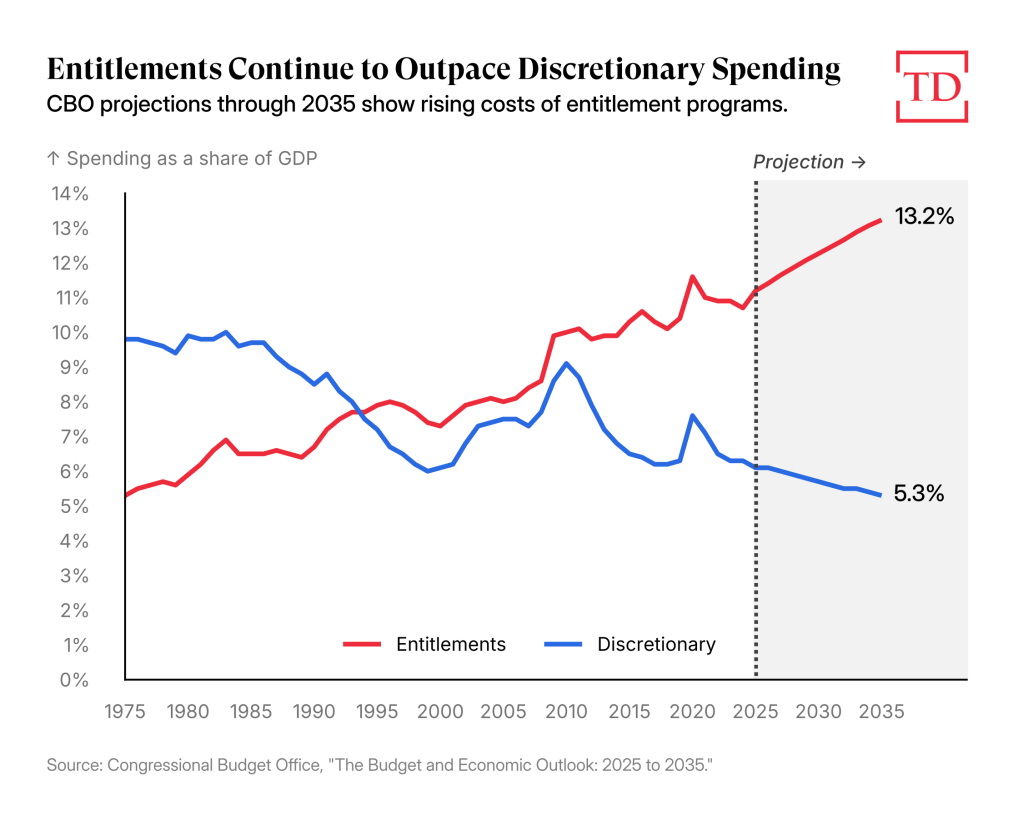

The reason that even deep discretionary cuts wouldn’t offer a solution to the budget problem is simple: The budget problem is an entitlement problem—it has been so for half a century—and it is only getting worse all the time.

This is the chief source of the intense self-deception that characterizes our budget debates. Many Republican deficit hawks have spent decades insisting that the trajectory of our debt could be transformed by cutting discretionary programs they don’t like. But all domestic discretionary spending is now about 14 percent of the federal budget, while entitlement spending amounts to more than 50 percent, according to CBO figures. More importantly, the growth in federal spending is heavily concentrated in entitlement spending, while discretionary spending is declining as a share of the budget and the economy.

It simply isn’t possible to offset the coming growth of Social Security and Medicare spending by curbing domestic discretionary spending. All the painful cuts Republicans are now negotiating as offsets to the reduced revenues in their tax bill are going to be dwarfed by the growth of entitlement spending on the elderly.

This means that any effort to seriously improve the fiscal trajectory of the federal government has to be focused on entitlement reform. There is no alternative. Many Republicans used to acknowledge this openly until about 2017. But although the underlying problem has only grown worse, the GOP has mostly stopped pursuing entitlement reform.

To the extent that DOGE targeted entitlements, it focused on marginal management costs, or on phantom targets (like 150-year-old Social Security recipients who don’t really exist). In the reconciliation process, there have been some efforts to curb Medicaid spending, but the most expensive entitlements—Social Security and Medicare, which provide benefits to the elderly and have grown to well over a third of the overall federal budget—have been off the table. Not only has President Trump pledged not to touch them, his call to end the taxation of Social Security benefits would increase the program’s costs and provide well-to-do seniors with even more benefits.

Curbing the growth of the old-age entitlements would be no simple matter, of course. Ideas for how it might be done are plentiful—I’m partial to the related proposals of my American Enterprise Institute colleagues James Capretta (on Medicare) and Andrew Biggs (on Social Security). But the will to take it on is hard to come by. That’s understandable, if not excusable. But it is not sustainable.

If Republicans are going to pursue politically complex spending cuts, as they are doing in the ongoing reconciliation battle, they might as well target the actual sources of our deficit and debt challenges, rather than expending immense political capital to no significant long-term effect by focusing on domestic discretionary spending.

Taking on entitlement reform will require a different way of thinking and speaking about those programs—understanding them as transfer programs rooted in intergenerational commitments, rather than as untouchable savings programs. Balancing gratitude to the past and solicitude for the future would help policymakers explain why they need to protect these programs but also to shield the rising generations from fiscal disaster. But of course, taking on such work would also require bipartisan accommodation, which our fiscal politics has sorely lacked.

The absence of bipartisan interest in budget reform is not the fault of Republicans alone. Most Democrats in Washington don’t even pretend to care about deficits most of the time, and when they do, they talk as if higher taxes on the wealthy alone could solve the problem.

But the fact that Republicans do pretend to take these problems seriously is precisely the reason to hold them to account. Most elected Republicans (like most Republican voters) believe there is an urgent need for fiscal reform. But most also seem to believe that they are engaged in such work now, and they must grasp that this is not true. Otherwise they run the risk of repeating a dangerous mistake from the Tea Party era: By persuading themselves that they are focused on the right targets, they will come to blame the usual suspects—squishy party leaders and entrenched, corrupt elites—for the failure to address the country's fiscal challenge. So they will leave the Trump era even more persuaded of their own rectitude and of the corruption of the larger system.

But that simply is not what is happening here. Republicans in the age of Trump are on a path toward failing to address the country’s fiscal problems because they are not being honest with themselves about what meaningful fiscal reform would need to involve, what budget policy they are in fact pursuing now, and just how little those two have to do with each other.

Ignoring the fiscal challenges our government faces is bad enough. But today’s GOP is pretending to address them while actually making them worse.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.