When Andrew Jackson won the 1828 presidential election, his victory also set into motion a political shift that would result in a party built to oppose a demagogue: the Whigs. In the wake of Donald Trump’s return to power, today’s Democrats would do well to study the Whigs’ rise, with both their successes and stumbles.

The parallel is inexact, as historical analogues always are. Jackson’s victory was more emphatic, with him winning 68 percent of the Electoral College vote compared to Trump’s 58 percent and more than 55 percent of the popular vote compared to Trump’s roughly 50 percent. The 1828 election was early in the history of our republic, when political parties were more in flux than they are now.

But Trump likes to compare himself to Jackson, a fellow celebrity who led a revolt against the establishment of the time, and the comparison is more compelling now than it was when Trump won in 2016. This is due not only to the fact that Trump won the popular vote this time, but also to how he got there. Like Trump in 2020, Jackson reacted poorly to defeat. He thought himself rightfully elected in 1824 and denounced his exclusion from office as a “corrupt bargain” between his rivals (he received the highest vote share, but none of the four candidates received a majority of the Electoral College vote and the winner was decided by the House). His 1828 campaign was imbued with a desire to avenge that perceived wrong—“retribution,” you might say. Two of his salient policies were similar to Trump’s: a purge of the civil service (“to the victor belongs the spoils”) and mass deportations (of the Five Tribes).

In both cases, the vengeful demagogue kicked aside opponents whose appeal had become too limited to prevail nationally. Today it was the Democrats (who, ironically, trace their origin to Jackson). In 1828, it was a faction led by incumbent President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of State Henry Clay that later became known as the National Republicans. Both election campaigns had been bitter and personal. The defeated parties feared, not without reason, that their victorious rivals would attempt to govern as autocrats.

Yet politics continued, and the National Republicans had to figure out how to mount an opposition capable of reclaiming a majority from the surging populists after their 1828 defeat. They flunked their first attempt when Clay ran against Jackson in 1832. The National Republicans largely stuck to the policy mix and rhetoric they were habituated to in the hope that Jackson’s 1828 success had been an aberration, and the result was that Clay lost by an even larger margin than Adams had.

Jackson’s opponents tried a different approach after 1832: expanding their electoral coalition by loosening their ideological bounds. The National Republicans’ desire for an expansive federal government role had largely confined their appeal to New England and the smaller mid-Atlantic states. To compete in the South and Midwest, as well as in Pennsylvania and New York, they had to make room in their party for states’ rights proponents and Anti-Masonic populists without alienating too much of their existing base of northeastern merchants and professionals.

The Whig Party, organized in 1834 by cobbling together various factions, was therefore an odd bunch. Some of its members, such as Clay, had been lifelong Democratic-Republicans, the party founded by Thomas Jefferson that Jackson’s rise had split. Some, like Adams and Massachusetts Sen. Daniel Webster, had ties to the defunct Federalist Party of Alexander Hamilton. Others, like New York Rep. Millard Fillmore, were Anti-Masons who disliked that Jackson was a Freemason, but could overlook the fact that Clay was one too. Others still, such as North Carolina Sen. Willie Mangum, were Jacksonian defectors who responded to the Whig founders’ outreach to Southerners.

These factions generally supported infrastructure projects, pro-banking policies and government intervention to support economic recovery in downturns. But they differed widely on slavery and to a greater or lesser degree on a host of other issues: tariffs, temperance, the re-chartering of the Bank of the United States, and the respective roles of the federal and state governments, to name but a few. When they agreed on things, they often did so for different reasons, and it took time for them to cohere, as Michael F. Holt traced step by step in his 1999 book The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party.

What the Whigs had from the beginning, however, was a unifying purpose: opposing the populism of Jackson and the drift toward autocracy they believed it exhibited. Their unusual name came from the British (who have a penchant for unusual names). The British Whigs generally aimed to limit the powers of the monarch, and they led the opposition to King George III during the American Revolution. The American Whigs meant to oppose the man they styled “King Andrew” and his movement, and to keep them within the bounds of the Constitution. Differences in opinion on other matters could be tolerated.

“The politics of addition is necessarily an uncomfortable and somewhat incoherent business.”

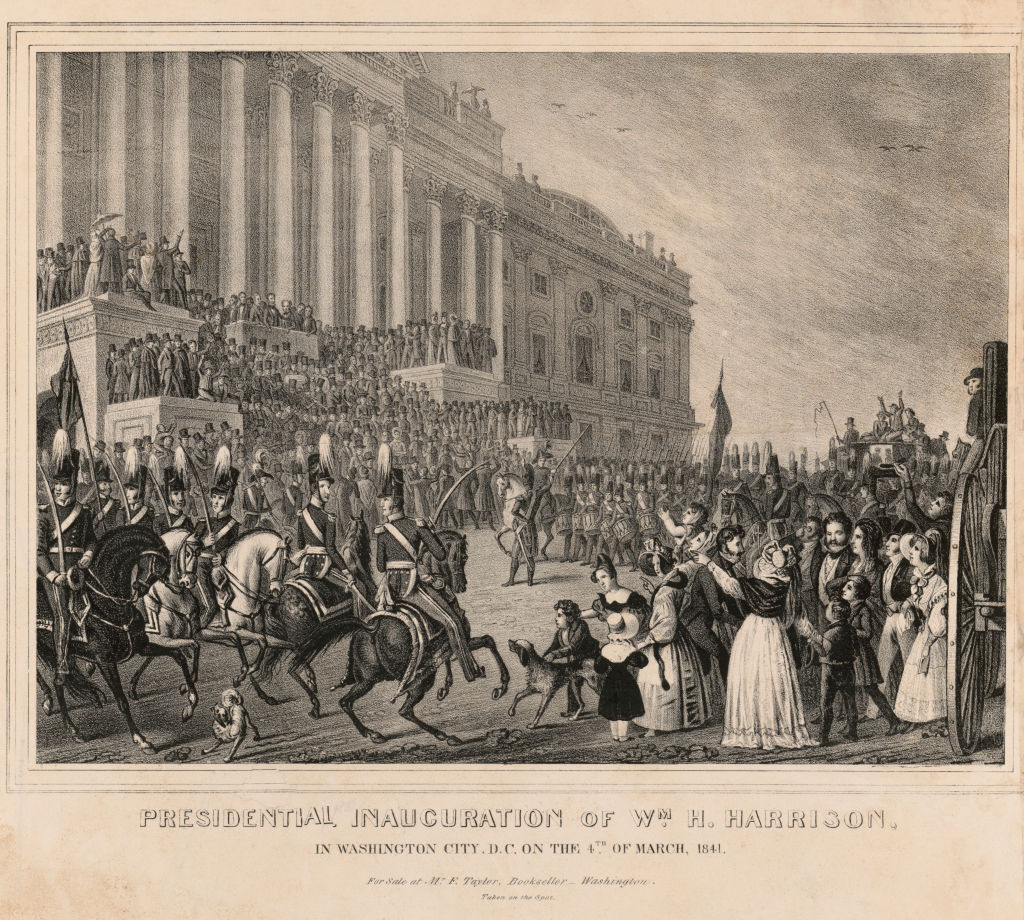

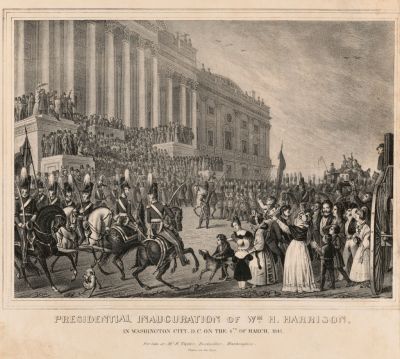

Gradually, this expansion strategy paid off. The Whigs gained seats in Congress in 1836, 1838, and 1840. They failed to defeat Jackson’s anointed successor, Martin Van Buren, in the 1836 presidential election, possibly because they employed the unconventional strategy of fielding several candidates. But they won in a near landslide in 1840 after Van Buren was left holding the bag during the financial panics of 1837 and 1839, crises that were likely exacerbated by Jackson’s populist dismantling of the aforementioned national bank.

The Whigs were well-positioned to exploit the Jacksonians’ stumbles because they both offered a contrast and had a political base large enough to mount an effective challenge when the opportunity arose. Whig candidates could stoop to populist gestures, such as William Henry Harrison’s “log cabin and hard cider” campaign theme, but the business-friendly Whigs were not a populist party. They tended to appeal more to the better-off, but they crossed geographic and ideological lines: Their base encompassed East Coast industrialists and Midwestern shopkeepers, Northern abolitionists and Southern slaveholders. The Jacksonians attempted to attack the Whigs as out-of-touch aristocrats, as they had done successfully against the National Republicans, but the potency of that accusation faded as the Whig coalition broadened.

Democrats today can—and should—learn from the mistakes of the National Republicans and the early successes of the Whigs. That’s not to say they should want to be the Whigs, who proved to be a fractious and short-lived party that was plagued by bad luck (both of its elected presidents died not long after assuming office) and made several missteps once in power. Nor is it to say with certainty that the Democrats are doomed unless they make major changes to their political disposition. But there are warning signs from the election, in which once-solid parts of the Democratic coalition shifted toward Trump. Democrats should take seriously the possibility that their 2024 defeat could be a prelude to a harsher beating in 2028 if they do not expand their tent in the way the Whig founders did.

The good news is that the victory margins for Trump and congressional Republicans were relatively small, and Trump is ineligible to run again. The Democrats should be able to reclaim the majority much more quickly than Jackson’s opponents if they take even a few steps toward broadening their coalition.

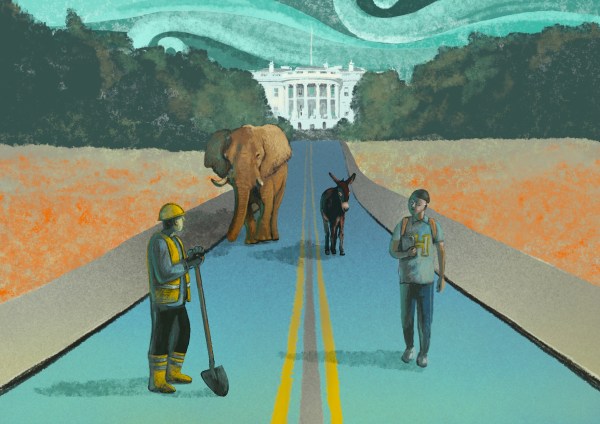

Of the many steps they could take, dropping “woke” rhetoric about race and gender is probably the necessary first one. Allowing some internal dissension on abortion could counter Trump’s expansion of the Republican tent on that issue and bring more religious voters into the Democratic coalition. An economic pragmatism that promotes ethical competition and eschews fixation on price gouging could woo small and medium business owners and position Democrats for a scenario in which Tariff Man trashes his and the Republicans’ reputation for economic competence.

Those are far from the only options. Party leaders and Democratic voters will have to sort out which new ideas and allies are palatable to them. Perhaps they decide they can play ball with neoconservatives, but libertarians are a bridge too far. So be it.

What is necessary is that Democrats offer their would-be fellow partisans more than a “place for you in our campaign” and stump appearances with conservatives like Liz Cheney. They would need to make concessions in their platform and allow Democratic candidates in different states and counties to hold positions that many in the party now might feel uncomfortable with, and do so without simultaneously condemning them for their positions. The politics of addition is necessarily an uncomfortable and somewhat incoherent business.

What could a Whiggish Democratic Party unite around? Connecticut Sen. Chris Murphy’s recent suggestion of “power de-concentration” could be a rallying cry if focused not just economically, as he intended, but politically with the aim of restraining the executive branch. Democrats could run in the 2026 midterms on a platform of reclaiming for Congress some of the many powers it has delegated to the president over decades. Such a pitch may have broad appeal if Trump spends his first two years back in office indulging his worst impulses. A big-tent Democratic Party might also rediscover the virtues of federalism and push for decentralization of some decision-making to the states and to local governments within states.

These stances could be political winners; they would also be good for the long-term preservation of the republic. In that way, they would hearken back to the best ideals of the American and British Whigs. When faced with an overreaching monarch or a demagogue who gives every indication of wanting to rule in monarchical style, it is healthy to have an anti-monarchical party. For all its faults, the Whig Party blunted the Jacksonian revolution. It also provided a political home for a young lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. There are far worse examples to emulate.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.