When Gov. Tim Walz of Minnesota appeared to claim in campaign appearances and media interviews that he and his wife used in vitro fertilization (IVF) to conceive their children, was he being dishonest? Or was he seizing on the pro-family nature of fertility treatment to frame it as a motherhood-and-apple-pie issue?

At a time when more couples and individuals are resorting to them, fertility treatments are increasingly being discussed in political campaigns. And courts and state lawmakers are introducing legislation both to protect and regulate them. Fertility treatments affect far more than the 1 in 10 women who’ve received them. According to a 2023 report from the Pew Research Center, 42 percent of U.S. adults have used fertility treatments or know someone who has (up from 38 percent in 2019). Walz and his wife used a different fertility treatment, not IVF, to have children, so it may be helpful to know something about these medical techniques and how they differ.

For couples in their prime childbearing years, getting pregnant is relatively easy. Anywhere from 40 to 60 percent of healthy couples under age 30 who are trying to get pregnant will conceive in three to four months.

For others, conceiving is not so simple. Men and women are equally prone to fertility problems—9 percent of men and 11 percent of women. Twelve to 15 percent of couples can’t conceive after one year of unprotected sex, and 10 percent still cannot after two years, according to the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Because lifestyle factors and medical issues can get in the way of conceiving children, fertility treatments are varied, and some couples use more than one method. Most couples receive the most basic treatment, fertility advice. This can range from making lifestyle changes—quitting smoking, drinking less alcohol, losing weight, engaging in more physical activity—to having more sex during ovulation and (for men) avoiding medications that can compromise fertility. Of all women receiving fertility treatment, 78 percent received advice.

Fertility drugs act like hormones, and for women are used to trigger ovulation or to stimulate the production of better or more eggs. Men may get estrogen blockers or hormones, both of which increase sperm production. Drugs to improve ovulation are one of the more common fertility treatments for women, received by 43 percent of all women who undergo fertility treatment.

In some cases, surgery may be used to restore the reproductive system in women and men. This can include removal of uterine polyps, scar tissue, or fibroids, or opening a blocked fallopian tube. Surgery can also mend blockages in vessels carrying sperm, fix varicose sperm vessels, or make other repairs.

Heterosexual intercourse certainly has its virtues, but efficiency may not be among them. Just 5 percent of all sperm introduced during sex—a few hundred—makes the upstream trip into the fallopian tube for the patiently waiting egg. To increase the odds of sperm-and-egg union, artificial insemination—or, as it’s called nowadays, intrauterine insemination (IUI)—places millions of paternal or donor sperm closer to the egg. Less expensive and invasive than IVF, IUI can help couples with medical conditions, couples using a surrogate, and single women to conceive. Only 14 percent of all women receiving fertility treatment use IUI, which is the treatment the Walzes used to conceive both their children, his wife later clarified.

For the most intractable infertility cases, in vitro fertilization, or IVF, is the most common assisted reproductive technique. Still, just 2 percent of women who receive fertility treatment undergo IVF, according to Pew Research.

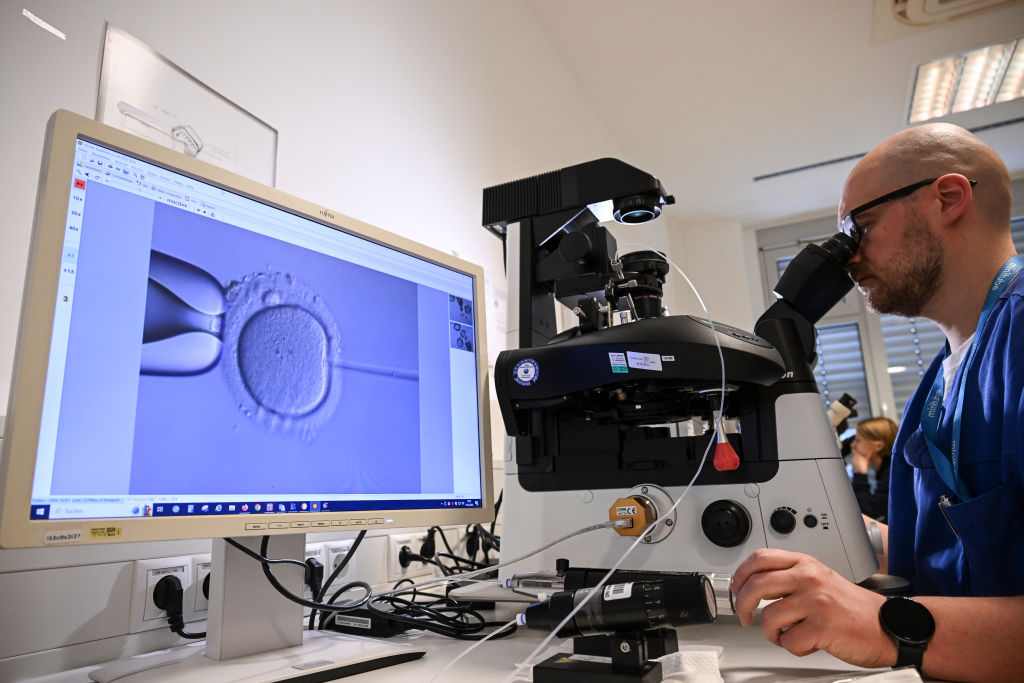

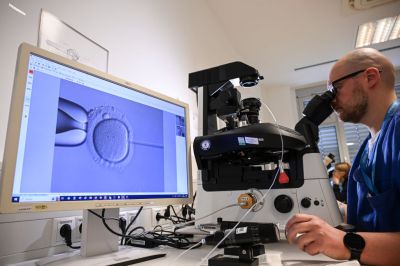

IVF is a series of procedures that typically begins with fertility medicine to spur the ovary into making eggs. Once those eggs mature, they are removed and, in a laboratory, fertilized with healthy sperm. The fertilized eggs—embryos—are either returned to the uterus or frozen for reinsertion later.

There are many variations on IVF that address specific fertility problems. For example, if the semen is questionable or if previous attempts at IVF have failed, a mature egg can be injected with a single healthy sperm, a technique called intracytoplasmic sperm injection. If the lining of the mother’s uterus is problematic, assisted hatching, where the outer layer of the embryo is opened to encourage planting in the lining, may be used.

Same-sex couples, single women, and couples who want the option to conceive in the future (for example, because the mother is being treated for cancer) have a number of IVF options. These include donated eggs, sperm, or embryos that can be tested to ensure their genetic health. These options often involve another woman—a “gestational carrier”—who carries the embryo to term. Couples may also extend their fertility using IVF and freezing and storing the resulting embryos for later use. In fact, about 40 percent of all people receiving IVF use it to bank their eggs or embryos. Sperm, eggs, and even ovarian tissue may also be frozen and banked for later use.

“Insurance coverage for fertility treatment varies widely, although 21 states and the District of Columbia mandate that employers provide some kind of coverage.”

Fertility treatments have their risks. These include fertilizing or implanting two or more eggs, which can increase the mother’s chances of gestational diabetes. Such multiple fetuses are likelier to be premature, which may present health and development issues after they’re born.

IVF in particular entails a higher risk of ectopic pregnancy, in which the embryo implants itself outside the womb—often in a fallopian tube. And of course, there’s the considerable risk that any fertility treatment regimen, including an IVF cycle, fails entirely and must be repeated. It takes 2.5 IVF cycles, on average, to become pregnant. The likelihood of a full-term, normal-weight live birth per IVF cycle is more than 20 percent for women younger than 35, and decreases for older women. As Walz said, infertility is a journey of “desperation that can eat away at your soul.”

Insurance coverage for fertility treatment varies widely, although 21 states and the District of Columbia mandate that employers provide some kind of coverage. Fifteen states (plus D.C.) require employer-sponsored health insurance plans to cover IVF, and where coverage isn’t mandated, it’s more likely to be found at larger companies. Covered or not, the high cost of many fertility treatments means the largest share of women receiving it are white or Asian, older, more educated, and upper-income. Just one IVF cycle may cost anywhere from $15,000 to $20,000, to beyond $30,000, and again, most successful IVF conceptions require more than once cycle.

Patients, health providers, and advocates for fertility treatments were shaken in January, when the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos are “children” in a case allowing a fertility clinic to be sued for the negligent destruction of embryos. Some IVF clinics in the state immediately paused their operations, leaving couples in the midst of treatment in temporary limbo. Just over a week later, the legislators in this very pro-life state proposed legislation that would give immunity to clinics performing IVF. A bill was passed in March.

The Alabama court’s decision has forced lawmakers and constituents in other states to reckon with the ethics of IVF for the first time in a while. In the 18 other states that have effectively given personhood rights to fertilized embryos, a judicial decision like Alabama’s is now more plausible.

But just as with abortifacients (medicines that induce abortion), interstate shipping may effectively moot some state laws. For example, Louisiana’s ban on the disposal of viable embryos in the 1980s ultimately had little effect on its residents’ access to IVF, as Louisianans generally store their embryos in states where disposal is legal.

When lawmakers in the red state of Alabama work overtime to preserve IVF, maybe it’s safe to assume that this and other fertility treatments are just too popular to ever be outlawed. Indeed, Pew found that by a wide and consistent margin, most U.S. adults believe health insurance should cover fertility treatments. (Men and Republicans are a bit less inclined to think so.) Judging by the resolve of the many women and their families to radically change their lives—sometimes selling their houses—to afford a shot at having a child, fertility treatment isn’t going away anytime soon.

Correction, August 30, 2024: The photo caption accompanying this article has been updated to remove an incorrect reference to an electron microscope.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.