How long has gerrymandering been a part of U.S. politics? Consider that the man who gave the strategy its name wasn’t some conniving Lee Atwater-style operative from the 1970s—he was a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Elbridge Gerry (pronounced Gary, not Jerry) was a Massachusetts politician, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party who would serve as vice president to James Madison. His was a very full and significant career: He signed the Declaration of Independence and did good service helping to supply the Continental Army with critical goods. He was a member of the Constitutional Convention, although he opposed the final document and refused to vote for ratifying it. (He was one of three holding out for a bill of rights.) He was also at the center of the XYZ Affair, which involved the French foreign minister Talleyrand demanding bribes from Gerry and other U.S. diplomats dispatched to France and led to the “Quasi-War” between the two former allies. Most important, Gerry was a persistent critic of centralizing power in the federal government at the expense of the states—an issue that was not, in spite of what one sometimes hears, an exclusively Southern concern. John Adams wrote of Gerry’s service in Congress: “If every Man here was a Gerry, the Liberties of America would be safe against the Gates of Earth and Hell.”

We sometimes spit the word politician in much the same way we hiss the word bureaucrat, which may be emotionally satisfying—unless you start to think very much about what the alternative to politicians and bureaucrats actually is. What a free republic wants is not to be free of politicians and bureaucrats but to have excellent politicians and bureaucrats.

And Gerry was a politician in an age that saw the young republic very much blessed by the quality and energy of its politicians—politicians who were every bit as subject to the same temptations and limitations as the ones we have today. Gerry, who had been suspicious of political parties per se earlier in his career, became a partisan Democratic-Republican and was, as the dictionary attests, not above drawing a political map in his party’s interest.

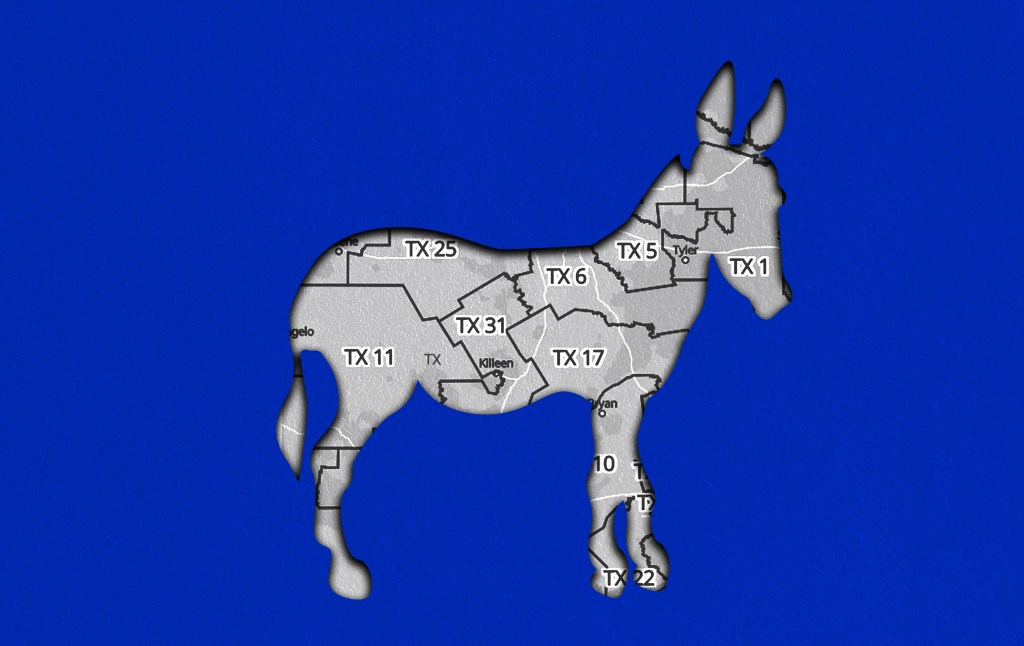

When I was young and idealistic, I asked a veteran of politics in Texas—where Republican plans to try to squeeze a few more House seats out of the map are at the center of the current phony outcry over gerrymandering—if the redistricting process might be too politicized, if there weren’t some more honest way to go about it. I got a much-deserved scoffing at, bordering on a scolding: “Redistricting is the most political thing a legislature does,” he said. Trying to take the politics out of redistricting is like trying to take the crab out of crab soup.

Gerrymandering is a fact of political life in many Republican states and in many Democratic states. Democrats did not complain about it very much until Republicans had the bad manners to get good at it, in part by doing one of the most un-Republican things Republicans have ever done: embracing technological innovation and surpassing the Democrats’ efforts to apply it to their political interests.

Should Texas Republicans forbear using their power to redraw the map to fortify their party’s position in the House? Maybe. And maybe those ethanol bastards shouldn’t lean on legislators to write fixed demand for their bulls–t corn juice into the law. And maybe California Democrats should organize public education in a way that puts students’ interests over those of public-sector union goons. There is a whole galaxy there in the word should. Maybe some of that good stuff will come to pass.

I am generally against procedural maximalism. For example, I am very much in favor of using the filibuster—sparingly. I am very much opposed to threatening to pack the Supreme Court every time it throws a monkey-wrench into Planned Parenthood’s business model, even if the Constitution provided a mechanism for doing so. That said, I’d rather see explicitly political stuff, such as redistricting, warped by political self-interest than I would education or economic policy or Bureau of Labor Statistics data or interstate-commerce jurisprudence. (Some people are libertarians because they trust people; some people are libertarians because they don’t.) You think the interstate highways were put where they are because the routes are rational? You think military installations have been anchored in certain congressional districts randomly? That is not how the world works, Sunshine.

Not that I think that describing a practice or proposal as politically unrealistic is an answer to principled objections to it—but one does not, in fact, hear very many principled objections to gerrymandering.

Before Texas Democrats were a minority party whose members scooted across the border to Oklahoma or, more recently, to Illinois (via private jet) every time a big vote threatened to go against them, they were a deeply entrenched majority party in the Lone Star State, and gerrymandered the ever-loving snot out of it, as their fellow partisans in California and Illinois have in their states. In fact, Democrats’ threats to retaliate against gerrymandering by Texas Republicans have been undercut by the fact that there isn’t a lot of room for additional gerrymandering in most states with longstanding Democratic control. I’ll believe Democrats are serious about the supposed menace of gerrymandering when the 13th House District in Illinois doesn’t look like a boa constrictor that has swallowed Beaver Dam State Park.

Funny thing about all those years of Democratic gerrymandering in Texas: It didn’t save them. When Texans decided they didn’t want to be governed by Democrats anymore (we loved the ebullient progressive populist Ann Richards more in theory than in practice) the state swung Republican and swung hard, and it has, so far, stayed that way. Gerrymandering did not save Democrats in Alabama or Tennessee or lots of other former Democratic states, either. The same holds true for former Republican strongholds. Republicans at one time controlled the California State Assembly (and the great majority of all elected offices in the state) for nearly 40 years, and three out of four California voters were Republicans in 1920—but there was a Democratic majority by the middle of the 1930s, and no kind of political deck-stacking was going to save the GOP majority in California from the Great Depression.

When battered Republicans complained that Democrats were pulling out all the stops to pass the woefully misnamed Affordable Care Act, President Barack Obama offered them some useful advice: Try winning some elections. The problem for the esteemed gentleman from Illinois was that his brand of politics ensured that he was basically the only Democrat who was going to win an election for about a decade.

In 2009, President Obama’s party controlled both chambers of 27 state legislatures. Eight years later, Democrats control both chambers in only 13 states. Among the states that slipped from Democratic control are Wisconsin, North Carolina, Iowa and West Virginia; states key to the victory of President-elect Donald Trump last November. According to a report from the National Conference of State Legislatures, the Democratic Party has lost a net total of 13 Governorships and 816 state legislative seats since President Obama entered office, the most of any president since Dwight Eisenhower.

President Obama entered the White House with his party touting a 60 seat majority in the Senate and 257 seat majority in the House. Democrats now hold a 48 seat minority in the Senate and 194 seat minority in the House — a net loss of 12 and 64 seats respectively.

If your party loses 800-plus legislative seats, you can’t be too surprised when the legislatures start doing things you don’t enjoy. Give the other side a state-level trifecta, and you’re going to get treated to the occasional pineapple suppository.

Democrats are not right on the verge of flipping Texas, but they could be doing better than they are: The state is quickly urbanizing, which generally works to the Democrats’ advantage, and while Trump had a strong showing there in 2020, his share of the vote actually declined a bit from 2016 to 2020, suggesting that there is room for maneuver—and that candidates matter. But Texas Democrats have sought far and wide to produce such statewide contenders as Beto O’Rourke, who in 2018 pulled off the unlikely political feat of being even more of an unlikeable dork than Ted Cruz is. Before the Democrats ran the guy who lost to Cruz against Gov. Greg Abbott, they ran the sheriff of Dallas County, whom Abbott beat by almost exactly the same margin as Trump’s win over Kamala Harris: 56 percent of the vote, including 42 percent of the Hispanic vote and 16 percent of the black vote. Democrats must feel a little bit like Keith Moon’s tom-toms, but they have no one to blame but themselves.

If Democrats in Texas don’t like how the state Legislature is going about its business—well, the job doesn’t pay very much, but the Legislature has regular sessions only in odd-numbered years, so there’s plenty of time for a side-hustle or three. Get after it.

But spare us the phony moral indignation. If the Democrats are, as they like to boast, the heirs of Thomas Jefferson, they’re the heirs of Elbridge Gerry, too.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.