The Justice Department is investigating what went wrong in the handling of three tranches of Obama-era classified documents recently found in President Joe Biden’s Delaware home and an affiliated think tank.

Special counsel Robert Hur hopes to learn whether Biden or his staff broke any laws connected with the discovery, transport, or turnover of classified documents. The process shouldn’t be complicated, as federal law and well-established protocols already dictate what’s supposed to happen with classified documents at the end of an administration.

Who can handle classified documents?

The Presidential Records Act of 1978 dictates that all presidential and vice presidential records—classified and unclassified—be turned over to the National Archives at the end of an administration. That usually falls to aides of the outgoing presidential administration who have appropriate security clearances, according to National Security Institute Founder and Executive Director Jamil Jaffer.

“There are all sorts of rules about moving classified documents from point A to point B,” said Jaffer, who previously served under former President George W. Bush as an associate counsel to the president. “The White House staff will gather up either their own files—or the files they are responsible for—and the White House and will consolidate them into boxes for the National Archives, labeled and indexed with a table of contents.”

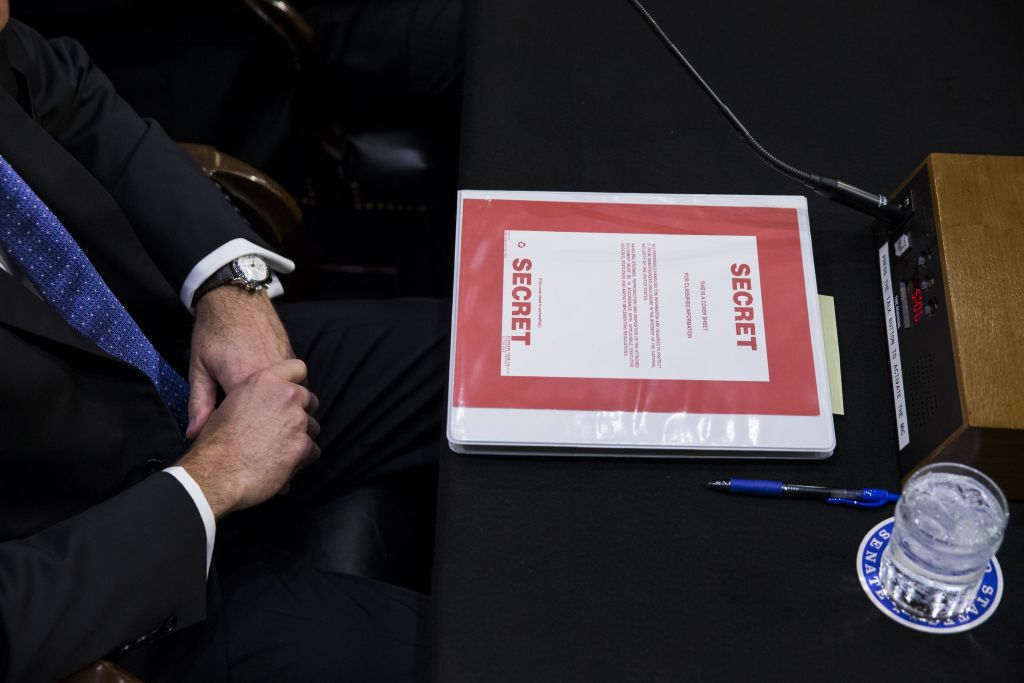

From there, archivists (who themselves must have security clearance) at the National Archives handle and store them according to the three levels of classification dictated by the Obama-era Executive Order 13526 governing confidential, secret, and top secret information. Even stricter measures are taken to secure sensitive compartmented information (SCI): the highest level of classification.

Does intent matter?

Any unauthorized handling of classified material constitutes mishandling, but criminal mishandling of federal documents requires intent, according to the Title 18 of the United States Code. The unauthorized mishandling of national defense-related federal documents is also prohibited under the Espionage Act of 1917.

It’s not unheard of for government employees with clearances to accidentally carry a classified document out of a secure location, or for a stray classified document to get swept up in other materials. But protocols mandate a quick and transparent response overseen by departmental security officers, who manage the handling and storage of classified materials.

“As soon as you realize that though, you have an obligation to immediately notify your security officer,” Jaffer said. “They’ll describe to you what action to take to protect the classified materials and secure them properly. And more often than not, that error will get noted in a security log. Moreover, if this happens repeatedly, is intentional, or is particularly egregious, it’s very possible you could face significant penalties, up to and including losing your security clearance.”

Even confidential material—the lowest gradation of classified information—must be treated carefully at all times, said Michael Allen, managing director of the international security firm Beacon Global and a George W. Bush administration national-security official.

He described a national security culture under the Bush administration in which high-level employees were “drilled with taking care of classified secrets all the time.” Allen said that while he worked in the White House, all of his meetings were conducted in what are called sensitive compartmented information facilities (SCIFs). All of the SCI documents he worked with were secured in a locked suite. If he had to transport them to Capitol Hill for a meeting, for instance, they were always secured in a double-locked bag.

“There’s definitely a hierarchy of seriousness, but at the end of the day, you’ve got to have a hard and fast rule that you can’t treat this information sloppily,” Allen said.

How does Biden’s mishandling of classified documents differ from Donald Trump’s?

White House lawyers discovered the first tranche of classified documents in the Penn Biden Center on November 2, according to Biden’s personal attorney, who said the president's legal team notified the National Archives of the documents’ existence the same day—one week before the midterm elections. The National Archives retrieved the documents the next day and notified the Justice Department of their existence on on November 4. Days later Attorney General Merrick Garland tapped John Lausch, the U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Illinois, to begin investigating the matter.

On December 20, Biden's personal attorney informed the Justice Department that Biden’s lawyers had found a second batch of Obama-era documents in Biden’s Delaware home. The FBI quickly retrieved them. But it wasn’t until January 9 when CBS reported the first set of documents that the public learned of their existence. Even though the White House confirmed the CBS report the same day, Biden's attorney declined to publicly disclose the existence of the second batch of documents in Biden's Delaware home until January 12 along with an additional and previously unreported document in Biden's home, and one day after several news outlets reported that additional Obama-era classified documents had been found in a non-secure location beyond the Penn Biden Center. On January 14 the Biden administration said publicly that they had notified the Justice Department of the discovery of five more pages of classified material in Biden’s Wilmington home.

Biden’s lawyers say his team has been cooperating with the Justice Department throughout the entire process. The Biden administration and the Justice Department originally considered having the FBI accompany Biden attorneys’ search of the president’s personal homes, but both parties decided against it, the Wall Street Journal reported earlier this week.

In the Mar-a-Lago case, the FBI retrieved from thousands of documents—dozens of which were marked classified—after federal authorities issued a warrant to retrieve them. Trump has also claimed that before he left office, he declassified the documents later found in his Florida home (even though they were still marked as classified when they were found).

Though the circumstances differ, in both cases classified information was found in non-secure locations well after both administrations were required by law to have turned over all presidential/vice presidential material to the National Archives. Both raise serious national security concerns about what kind of classified material is in the documents, who had access to the material, and for how long.

“They’re more similar than different,” Allen said. “When you boil it down, it’s mishandling of classified information, and that is completely inconsistent with the security culture of the national security community of the United States.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.