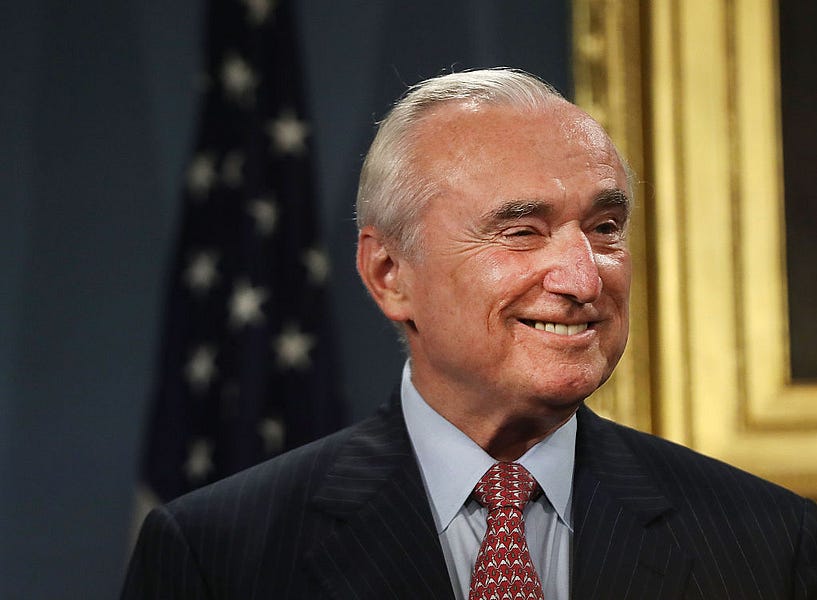

Bill Bratton has been here before. If anyone involved in the conversation around policing and rising crime rates in America’s largest cities can claim to feel a sense of deja vu, it’s the man who is arguably America’s best-known and most respected cop. Bratton has run the police departments in three major U.S. cities: Boston, New York, and Los Angeles. But it was his first stint in Gotham, where he and Rudy Giuliani oversaw a dramatic decrease in crime rates in the 1990s, that earned him a supercop reputation—and means he will forever be a New Yorker.

Bratton has leaned into that identity. He has long been a fixture of the Manhattan scene. He dials into our Zoom call from his weekend home in the Hamptons. Now 73 and installed in a plush private-sector sinecure, Bratton still sports a chunky gold and blue ring, a finger-width replica of his NYPD commissioner’s badge.

As soon as Bratton starts talking, however, he is unmistakably Bostonian, his accent revealing the town where, as he recounts in his new memoir The Profession, he “grew up in a working-class family on the second floor of a three-decker” and where, as a child, “he wanted to be a police officer since before I can remember.” And though he is out of uniform, Bratton is still the face of American policing to an extent that few active police leaders can claim to be.

It’s a tough time for law enforcement. Crime is rising and morale is low. Many large cities have heeded demands by activists to cut funding to their police departments. Others are “reimagining” public safety. And many officers don’t seem to like what that vision looks like. Retirements are up 45 percent and resignations up 18 percent nationwide. In big cities, the numbers are even higher.

Before getting into all of that, however, I ask Bratton about the nine minutes that set much of this in motion. “I’ve not seen anything like it in my career, and I’ve been in and around policing for 50 years,” he says of the murder of George Floyd. “I just couldn’t understand. I was shocked by it, angered by it.”

Bratton starts to say that he knew what would happen next but corrects himself: “Actually, I failed to recognize just how serious the repercussions were going to be. I don’t think anyone could have anticipated, watching, what the results were going to be over the ensuing days, weeks and months. There was so much going on when George Floyd occurred and, when it happened, it was so egregious that it wasn’t like throwing a match on all that kindling. It was like throwing a torch onto it. And it exploded.”

One of those unanticipated consequences was the emergence of the idea of defunding the police. “It’s one of the stupidest phrases that’s ever been concocted,” says Bratton. “And it boomeranged very badly on them. It was the phrase of the moment but when Democrats saw that Republicans were using it as a battering ram, they ran like hell away from it, appropriately so.”

Not quickly enough, however, to stop many cities from turning defund the police from slogan to policy. Last year, major cities across the country slashed police budgets. In New York, Bill de Blasio cut funding for the NYPD by $1 billion. Shortly after Floyd’s death, Minneapolis’s city council voted to “dismantle” its police department. But in the face of growing discontent about rising crime, many municipalities have reversed course. Minneapolis has backed away from its more radical plans. According to the Wall Street Journal, “in the nation’s 20 largest local law-enforcement agencies, city and county leaders want funding increases for nine of the 12 departments where next year’s budgets already have been proposed. As Bratton sees it, the folly of the defund movement lies in the reality that “so much of what the social justice and criminal justice movement are looking for actually calls for more expansive funding of the police. For better training, better research.”

Perhaps the most surprising thing about these funding decisions is that they were made against a backdrop of rising violent crime rates. In New York, for example, shootings have been on the rise for more than a year, and in the first five months of 2021 reached their highest level since 2002. Murders in the city jumped by 44 percent between 2019 and 2020. The cause of those increases is the source of considerable debate, but Bratton pushes back against the progressive argument that the pandemic and associated economic hardship is the primary cause of the problem. “New York was already struggling,” says Bratton. “The city’s crime problem began to accelerate after the legislature in the state passed their bail reform act [in 2019].”

Bratton calls this move, which abolished cash bail for the majority of crimes, “a bridge too far.” He argues that there need not be a tradeoff between law and order and criminal justice reform. “If you look at New York in 2018, in many respects we were there. We had reduced the jail population to about 9,000 from an average back in the ‘90s of 22,000. We were reducing the number of arrests and summonses. Cops were freed up from proactive policing and dealing with crime and disorder because there was so little of it left.”

This, Bratton says, meant there would be more time for exactly the kind of community engagement and relationship-building that can help relations between the police and minority communities. “But to the legislature in Albany it was as if none of this reform had happened,” he says.

In Bratton’s view, crime waves are referred to as epidemics for a reason: “It expands extremely rapidly, as we’ve seen with the coronavirus, but if you find the right measures, the right vaccines, it can decline just as rapidly.” As with public health crises, the policies needed in the midst of an outbreak are not the same as those needed when the numbers are under control again. “Isn’t that what happened in New York?” asks Bratton rhetorically. “We rapidly grew enforcement activity in the ’90s, but then as crime began to go down we were able to start reducing arrests and summonses.”

Three decades on, Bratton delivers a robust defense of the crime-busting measures with which he made a name for himself in the 1990s. Those policies, which once received bipartisan acclaim, are today viewed more critically among the bien pensant crowd and are the subject of accusations of racism from the left. Broken windows—the philosophy zealously embraced by Bratton and his partner-in-crime-fighting Giuliani, which calls for a zero-tolerance approach to petty offenses to help reduce serious crime—is now a tarnished phrase in many circles. A resolution introduced by House Democrats last year, for example, blamed broken windows for “mass criminalization, heightened violence, and mass incarceration that disproportionately impacts black and brown people.”

“I make no apologies for the activity in the ’90s,” says Bratton. “Arrests were the medicine that was necessary in [New York] and certainly in Los Angeles because we had no alternative at that time to break the back of the problem in what was an extraordinarily violent time.”

What does Bratton say to the charge of racism? “What we were targeting was crime,” he replies. “Unfortunately for the black population, most of it was occurring in their neighborhoods. Most of the victims were black or brown. We’d have been accused of neglect if we hadn’t attempted to deal with that crime problem.”

“Broken windows,” Bratton continues, “is the very essence of what everyone claims they want, that is community policing. What are the problems that they want prioritized and they want prevented? What are the problems that come into the NYPD every day in the thousands? Broken windows. Get rid of the prostitute in my hallway, get rid of the kids smoking dope up on the roof, get rid of the gang on the corner keeping me awake all hours of the night. Those are broken windows. And who is complaining about those broken windows? People in our poor neighborhoods.”

To accusations that police target black and brown communities, Bratton responds with a question of his own: “Why are the police in those neighborhoods? Because people are calling the police. This is the tension right now in the reform movement. They claim to be representing the interests of the poor and minorities, but who is in fact calling the police? It’s the poor and the minorities.”

For all that Bratton delivers a resolute defense of his record—and the case for robust policing—he is also open to the charge of blind spots and unintended consequences: “What have we learned since then? We are now much more mindful that a lot of the laws passed back in that era are having a compounding effect on trying to reintroduce some of those people back into society. … So the criminal justice reform effort of today is to try to find ways that people will still be punished for committing a crime but that you don’t give them an effective life sentence.”

He also acknowledges that even today, and even in cities like New York and Washington, D.C., where the police rank-and-file is majority minority, law enforcement often fails to treat citizens in a way that is “constitutional, compassionate, and consistent.”

“The black population is demanding: Treat us the same way as you treat others,” says Bratton. “We’re still not always seeing people the way they want to be seen.”

When he returned to the NYPD commissioner’s office for a second time, under Bill DeBlasio in 2014, curbing high stop-and-frisk rates in the city became a priority. A medicine that may have been necessary in the 1990s had grown counterproductive by the 2010s. As Bratton writes in The Profession, “the numbers ceased to be a means to an end and became an end in and of themselves.” Under his predecessor Ray Kelly, stops in the city had soared to nearly 700,000 a year. By 2015, the figure was 22,565.

Time and again, Bratton returns to the idea that crime fighting and criminal justice reform can go hand in hand. As he sees it, the former makes the latter possible. The choice between public order and a fair and equitable system of justice is a false one. Instead the challenge is getting the right prescription at the right time. “It’s fascinating when you look at just how many similarities there are between medicine and policing,” he says.

If police chiefs are having a tough time of it in contemporary American politics, then so too are self-styled “centrists” like Bratton. To run a police department is, argues Bratton, almost by definition, to be stuck in the middle “with partisan politics raging” all around. He reaches for an expression of Teddy Roosevelt’s to describe the police chief’s position: “the man in the arena, bloodied and battered,” he paraphrases. “That’s the American police chief today, black or white, male or female. … The role of the police chief in America today is probably the most difficult it’s ever been not only because of the politics of the moment but the challenges of the moment.”

One thing that doesn’t help is Republican Party’s double standard on law and order: on the one hand making the tough-on-crime, back-the-blue argument, on the other explaining away the violence of an attack on, among other things, law enforcement, at the U.S, Capitol on January 6. “Thank God for the actions of those cops that day,” says Bratton. “The reaction of the Republican Party and many individuals in that party has been obscene. … It’s an extraordinary source of frustration for me to see attacks on policing and support for those thousands of anarchists who were trying to overthrow our government that day. I’m very concerned for our country at the moment. And I’m very concerned for the policing profession who are right in the middle of it all.”

It is a gloomy note to end on, I say. “I always find hope,” says Bratton. “Nobody thought we could get New York out of the morass it found itself in after 25 years of crime increases. Mario Cuomo said maybe this is as good as it gets. But I was an optimist who thought we could do something about it. I still remain optimistic about the future. But we’ve got a very, very rough road ahead.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.