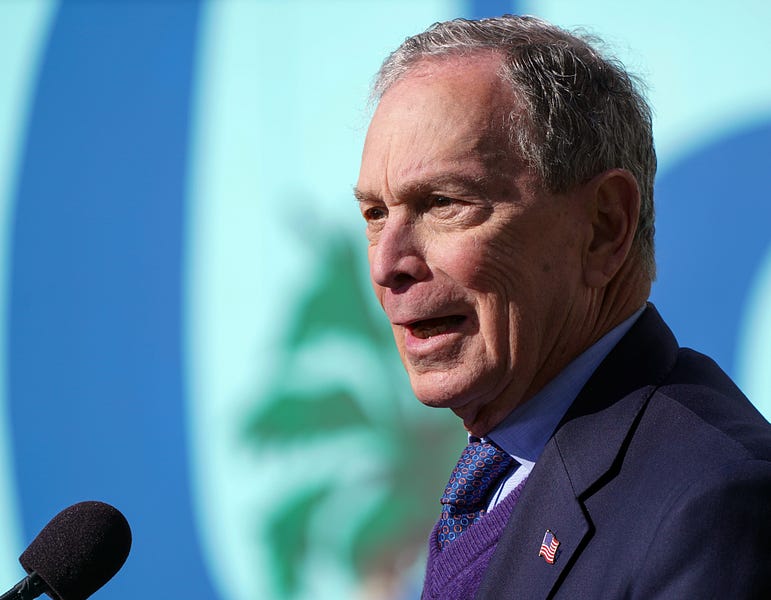

Just hours after Dixville Notch handed write-in candidate Michael Bloomberg a most unlikely victory in the five-vote town, opposition research began to fall like snow in the New Hampshire White Mountains.

Audio of Bloomberg defending the number of minorities targeted by his stop-and-frisk policies “resurfaced,” as did comments he made in 2015 about Russia annexing Ukraine that seemingly defended Vladimir Putin.

How does all this “resurfacing” happen? As someone who got her start in opposition research, I thought I could help demystify the process. Let’s dive in!

First, presidential campaigns and national party organizations may have their own research teams in-house (the RNC, for example, may have more than a dozen folks in its research department toward the end of a cycle) but the vast majority of campaigns use an outside vendor. Either way, these folks put together a “book” on each opponent. And these books run into the tens of thousands of dollars.

(Side note: A smart campaign hires someone to do a “self-vet” as well. This means putting together a book on its own candidate to prepare the team for what opponents can find and how they will pitch it to reporters. As one former practitioner told me, this can “lead to a lot of very awkward conversations.”)

So what goes in these books? Everything. Opposition research is about drawing a contrast between how an opponent defines his or her candidacy and reality. A researcher will start by cataloging everything the opponent has said—positions, biography, mission statement. Every public record that can be found—LexisNexis searches, voting records, property records, divorce records—will be used to find contradictions and inconsistencies.

Unlike the Hollywood version, these jobs are done behind laptops, not in alleyway dumpsters. It can be tedious, dry work in which a researcher leaves the office to travel to rural courthouses that may keep only hard copies of deeds. And the vast majority of what a researcher finds will be a dead end. Some researchers will have specialties in forensic accounting or a legal background. Some will be former legislative staffers that can pick apart a voting record more efficiently than a vulture with a carcass.

The tabloid stuff—infidelity and scandal—rarely makes the cut because everything in the book has to be meticulously sourced. If there’s not a citation, its not in there. As a former Republican communications strategist and opposition researcher told me, it doesn’t get in the book because there’s no where to sell it—”no legitimate journalist is running rumors without rock solid attribution.”

Once the book is put to bed, it gets handed off to the communications team to get it out there. When done correctly, this is a hand-in-glove operation. A great researcher can make a communications team look good. And a great communications team is made infinitely better by a good book.

And the information in the book can end up a lot of places: television ads, debate preparation, speeches, direct mail, and—of course—news stories. When a spokesperson calls a reporter with opposition research, they agree on an attribution in advance. Usually, both sides agree to “no finger prints.” This means that the reporter does not reference where he or she got the information in the story. This is another reason why it’s important for every line in the book to have publicly sourced attribution—it provides plausible deniability for the reporter to insinuate that he found the information himself.

The next decision is when to deploy the information in the book. Again, Hollywood would have you believe that every campaign holds their best stuff for an “October surprise” but that’s rarely the case. First, most people have already made up their minds about a candidate by then. If the information goes to trustworthiness or authenticity, that information is better deployed early as voters get to know a candidate. Romney’s role in Bain Capital, which largely came out before the general election had really gotten under way, defined his opponents’ narrative of him as an out-of-touch plutocrat. Second, it can fit into an existing news cycle. If Iran is in the news and your opponent said wacky things about the 1979 coup, that timing is important.

Third, old news can come back up in a new context. This is happening a lot in the #MeToo era and, as we’ve seen with Bloomberg this week, in the context of criminal justice reform. Fourth, it can be used in horse-trading away a bad story. When a reporter calls a campaign for comment on something small but damaging, a spokesman can offer a new and bigger lead that can get the reporter a front-page story in exchange for dropping the smaller one. Lastly, a campaign may want to pitch a story to a business journalist who will write a long-form piece about the opponent’s time as CEO, because then the story gets a second bite from the political reporters who can write off that story.

Most important consideration? “Maximum impact—getting the most eyeballs within a targeted voter demographic, written correctly,” said the former Republican operative.

Like so many other things in politics, Trump has changed the game as well. Before, it was a shibboleth of opposition research and political communications that it was always better not to have your candidate be the one to say something for the first time. That’s why it was important for a campaign to get a news story so the candidate could cite it at a debate, for example. When Biden got asked about Buttigieg’s record at the last debate, he demurred and then his campaign put out a video contrasting their records. But after years of Trump being his own best (and worst) messenger to drive his own news cycles, the Biden tactic felt stale and inauthentic. The rules have changed.

Can Bloomberg withstand what’s about to come his way? “That’s the $5 billion question,” said the former researcher.

Photograph of Michael Bloomberg at a campaign event in California by Scott Varley/MediaNews Group/Torrance Daily Breeze via Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.