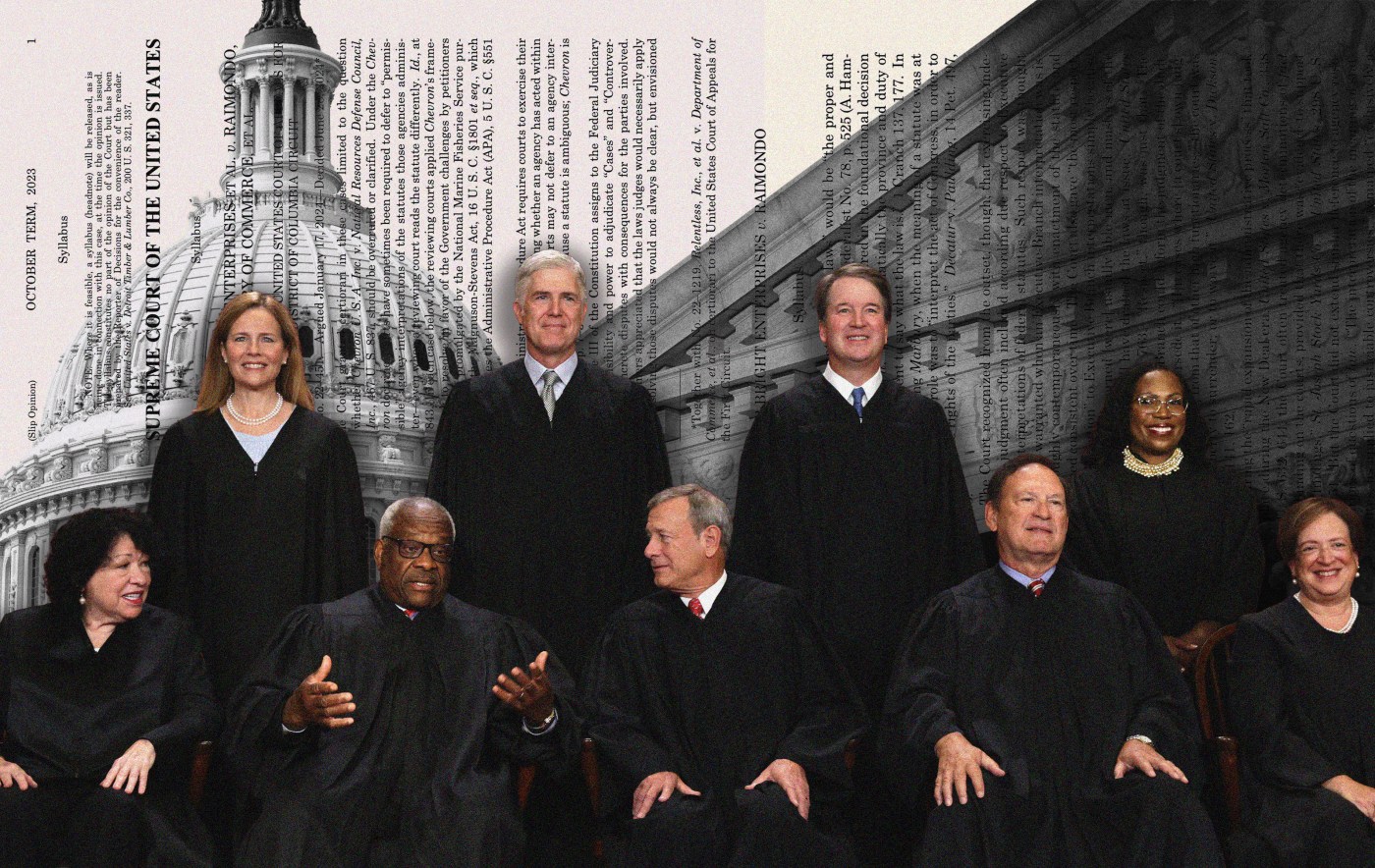

We may never see a better Supreme Court of the United States.

Since Amy Coney Barrett arrived in late 2020, the six-justice conservative-ish majority has, slowly but surely, set about fixing the court’s biggest mistakes of the last century. And American governing is better for it.

To understand the significance of today’s Supreme Court, we can’t assess each case in isolation. And we certainly shouldn’t focus on whether a particular decision handed President Donald Trump a win or loss. Instead, we should see that there’s been a movement afoot.

In one sense, the court is rolling back the two strands of left-jurisprudence that dominated for generations: liberalism and progressivism. With the former, the court manufactured new rights found neither in the Constitution nor in our history or traditions. That had the effect of enabling justices to read their own policy preferences into the law, tying the hands of elected officials. With the latter, the court allowed the federal government, particularly its sprawling bureaucracy, to centralize power away from the people.

To remedy those errors, today’s court hasn’t been especially “conservative,” if we understand conservative jurisprudence to mean a combination of institutionalism and originalism/textualism. Indeed, many of its decisions have been seismic rather than staid. And originalism isn’t doing much heavy lifting right now. Chief Justice Roberts (once again most frequent in the majority this term) doesn’t describe himself or present as originalist, some major decisions haven’t been primarily originalist/textualist, and there are live questions among the justices about how history, tradition, and precedent intersect with originalism.

Instead, the defining characteristic of this court—thankfully—is its commitment to American republicanism. Not Republican as in the political party. But republican as in distributed self-government and a reliance on an active, pluralist civil society. This puts the people in charge via elected representatives in state legislatures and Congress and through a constellation of close-to-home voluntary associations. This is the only way our diverse, continent-spanning nation of free citizens can flourish.

Sadly, the Supreme Court lost sight of that ages ago–starting during the Progressive Era and continuing through the New Deal era and then the Warren and Burger courts. Every time it created or expanded a right, it took power away from our political branches. The people and their elected representatives lost the ability to debate, negotiate, and then decide on the best course of action on many important matters. Judges too often took over that responsibility. The court also allowed Uncle Sam to play a bigger and bigger role in public life and empowered his insulated federal agencies to control large swaths of policy. This degraded the vital roles played by state and local governments and separated important policies from democratic decision-making. As a result, for generations power gravitated up (to the federal government) and in (to the executive branch) instead of down and out to states and communities.

America can’t work that way. Those decisions contributed to the nation’s ongoing, unprecedented dissatisfaction with institutions and this era of perpetual populism. The only thing capable of solving these SCOTUS-fueled problems is a SCOTUS oriented toward republicanism. And that’s what we finally have.

The outlines of this new direction became visible in the court’s first term with Justice Barrett. In 6-3 votes, the court deferred to state governments by upholding key Arizonan election rules challenged under federal law and upholding a Mississippi policy related to the sentences of juvenile felons. It strengthened civil society by protecting private groups from government efforts to monitor their donors, and it protected religious groups’ participation in government programs. It also took on “independent” federal agencies, executive-branch entities that can write regulations, conduct investigations, and impose penalties outside of the president’s control. The court ensured that these powerful officials are answerable to the democratically accountable president.

Over the next three years, the movement accelerated.

The court repeatedly limited the power of federal agencies. It ruled that one federal agency had overstepped in issuing pandemic-related rules and another had overstepped in forgiving billions in student loans. These were major decisions requiring congressional action, the court ruled. It also declared unconstitutional federal agencies’ practice of in-house adjudications of enforcement actions: If the Securities and Exchange Commission wanted to punish people like a trial court, it had to give them a jury trial like a trial court. Then, in its coup de grace, the court overturned Chevron, limiting the power of federal agencies vis-à-vis the judiciary and Congress: Courts no longer had to defer to agencies’ interpretations of law—Congress writes statutes, and courts interpret them

The court was also deferential to states and democratic decision-making. It affirmed the right of elected bodies to censure their members despite First Amendment claims and the right of Congress to collect executive-branch materials despite claims of privilege. It affirmed the authority of state constitutions to direct election processes and the power of states to regulate some commerce despite claims related to the “dormant” aspects of the Commerce Clause. It affirmed the constitutionality of local ordinances regulating camping on public property despite Eighth Amendment claims and the right of state governments to prosecute crimes by non-Native Americans on reservations. It strengthened the power of states to redistrict in the face of federal equal-protection claims—building on recent cases, including one that found states’ political gerrymandering is beyond the reach of federal courts. And in its most important decision, the court overruled Roe and Casey, returning the regulation of abortion to the voters.

The court also moved to protect civil society. It explicitly abandoned the Lemon test, which had marginalized faith-based groups for nearly 50 years. That opinion had invented a three-prong test for managing the relationship between religion and government. In practice, the test often required what amounted to state discrimination against faith. The court also clarified the right of religious groups to participate in education programs.

This year’s just-concluded term confirms the court’s republican direction. It affirmed the right of states to require age-verification for sexually explicit sites over First Amendment claims. It affirmed the right of states to regulate medical interventions related to transgender children. It put a stop to the out-of-control issuance of universal injunctions, thereby allowing the governing branches to govern without continuous federal-court interpositions. And the court continued to make independent federal agencies answerable to the elected president.

For generations, the court’s default settings were liberal and progressive. Claims of rights took precedence over democratic decision-making. Authority moved from states and communities up to the federal government, especially its executive branch agencies. Civil-society entities, especially its faith-based groups, were on the back foot. This had a profound, costly effect on public life. Pluralism deteriorated as power moved away from voters. The American concept of sovereignty had been changed: The people, acting through voluntary associations and their elected representatives in municipalities, states, and Congress, didn’t have the authority we wanted. The people had lost control. Now, however, we have a court that appears committed to restoring that control.

Today’s SCOTUS is by no means perfect. Its decision in Trump v. United States inhibits the ability of Congress to curb abuses of presidential power. In Bostock, which included gender and sexual identity under the federal rules against sex-based employment discrimination, it acknowledged that it was interpreting a federal statute in a way that the people’s elected representatives did not intend. In a series of gun-related cases, it made it harder—or at least far more confusing—for elected representatives to legislate in this area. And there is still work to be done. For instance, the court should reconsider the constitutionality of many independent agencies. It should reconsider the vast regulatory power given to the federal government. It should do more to protect the right of association. And, most importantly, it should breathe life into the Constitution’s long neglected Republicanism Clause.

But none of this should take away from the invaluable work done by this court over the last five years. No SCOTUS in recent memory, and possibly no SCOTUS in the last century, has taken American self-government more seriously.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.