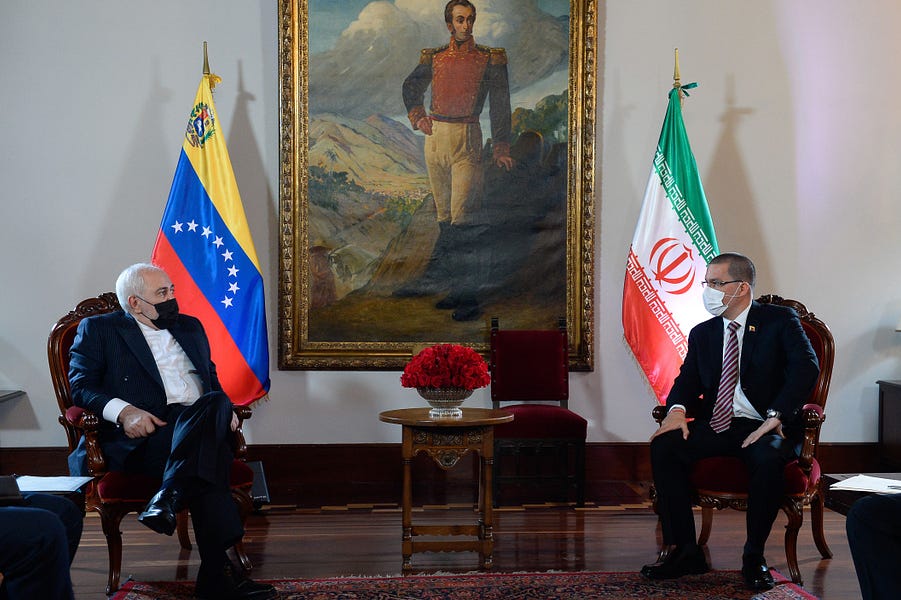

Is Iran escalating tensions between Washington and Caracas by delivering advanced weapons systems to Venezuela? In August, Venezuelan strongman Nicolas Maduro said that buying Iranian missiles was “a good idea.” Then, an Iranian cargo plane flew to Caracas on October 27, amid Twitter rumors said it was carrying advanced weapons systems, possibly missiles. And last week, during an official visit in Caracas, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Jawad Zarif pledged increased cooperation in defense areas, just as a second Iranian cargo flight, operated by the same plane regularly used by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards to deliver weapons to Syria, was heading to Venezuela.

Assuming advanced weapons are in the cargo, this would be a game changer, but the plane almost did not make it to its final destination. The mystery cargo flight from Iran to Venezuela was stranded in Senegal for 12 hours, and it looks like it was not a technical glitch. The U.S. might have intervened, and not for the first time.

Last spring, Iran’s Mahan Air undertook a two-week intensive airlift to bring assistance to Venezuela’s refineries, as the country was in the midst of a fuel crisis. (Mahan Air is under U.S. Treasury sanctions, partly for its role airlifting weapons and fighters to Syria.) Iran doubled down on its airlift to Venezuela by sending tanker ships as well, carrying gasoline in exchange for gold payments. The U.S. managed to interdict some of those shipments.

When, on October 27, a Boeing 747 EP-FAB belonging to the U.S.-sanctioned Iranian airline Qeshm Fars Air landed in Caracas, the United States appeared to be caught off guard. Just a day before, Elliott Abrams, the U.S. Department of State’s special envoy for Iran and Venezuela, had warned Iran not to deliver missiles to its South American ally, providing no further information about whether such a delivery was imminent.

Right on cue, that night, the jumbo cargo plane left Tehran, stopped over in Tunis, then flew to the West African island nation of Cape Verde, avoiding Algerian airspace, and eventually reached Caracas. The stopovers, with the aircraft twice on the ground for under two hours, suggested the plane carried a heavy cargo on board (on its way back the aircraft flew nonstop to Belgrade, Serbia, before returning to Tehran) and fueled rumors that missile components were on their way. Yet two days later Abrams went on record saying the U.S. did not know what was on the cargo. By then, the Iranian cargo plane had returned home.

There is no publicly available information yet about what Iran delivered to Venezuela in late October. But it looks as if the United States did not stand idly by when Iran tried to make a second delivery.

On the night of November 5, the wee hours of the next morning in Tehran, the same aircraft took off and headed for Tunis. Much like on October 27, the aircraft landed at its first destination without a glitch, stayed on the ground for under two hours to refuel, and then took off. This time, it headed southwest, but as it approached the Algerian border, less than a half hour after takeoff, it abruptly turned northward and headed to the Western Mediterranean, where, after flying briefly into Italian airspace over the island of Sardinia, it veered west and then southwest, heading to Cape Verde’s main international airport, Espargos. The sudden closure of Algerian airspace was not the only inconvenience. As it was making its final approach to the runway in Cape Verde, at an altitude of less than 3,000 meters, the Iranian cargo sharply turned around, regained altitude, and flew east to the nearby international airport of Dakar, Senegal, where it stayed for 12 hours.* That’s neither a regular flight pattern nor a refueling stopover. Something went wrong.

Eventually, the aircraft flew to Caracas, and on Sunday it flew back nonstop to Tehran—another anomaly, given that cargo planes on the Caracas-Tehran route have routinely stopped in Belgrade for refueling.

The days ahead will tell what really happened and whether this was a successful U.S. interdiction operation. If so, the diversion and inspection of a sanctioned plane and its cargo is likely to have significant repercussions and long-term consequences for U.S. foreign policy, which stretch well beyond Inauguration Day. The evidence possibly found on the plane may put the Tehran-Caracas axis on the spot. And Iran will not let the seizure of an Iranian aircraft—unprecedented despite more than a decade of terror finance and proliferation sanctions against Iran’s aviation sector—go quietly.

Regardless of the outcome, this is one to watch. The incoming Democratic administration will have to hit the ground running on this matter and cannot rehash Obama-era policies of détente with Maduro and his allies in Tehran. Iran never gave up on its ambition to expand its influence in Latin America as a counterweight to Washington there. It is also seen as an opportunity to consolidate a forward-operating base in the Americas, which would undermine U.S. interests, facilitate sanctions evasion, and potentially coordinate terror operations against Western targets. That is not about to change.

Neither should Washington’s posture vis-à-vis Maduro and Iran’s support for his illegitimate regime.

Correction, November 9: This piece originally stated that the Iranian plane descended to an altitude of 3,000 feet before it had to change directions and regain altitude to proceed to a different destination. The plane was at 3,000 meters.

Emanuele Ottolenghi is a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a nonpartisan think tank focused on foreign policy and national security issues. Follow him on Twitter @eottolenghi.

Photograph of Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif (left) with Venezuelan Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza (right) in Caracas, on November 5, 2020 by Cristian Hernandez/AFP/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.