The past few years have been bad for American foreign policy. Biden administration officials sailed into office with the serene confidence that once the adults—that is to say, they themselves—were in charge, the ship of state would right itself. The administration had a four-point plan to restore American preeminence. First, American forces in Afghanistan would gracefully exit and the War on Terror would finally end. Next, once the 2015 nuclear deal that Donald Trump had exited (JCPOA) went back into force, Iran would be cajoled into détente and the Middle East would stabilize. Third, Russia would be parked to the side, and the administration would tinker at the margin on Indo-Pacific security arrangements. All of that would leave Beijing so overawed by America’s nifty maneuvers that it would give up its ambitions for global preeminence and get to work on issues of mutual concern such as countering pandemics and climate change.

None of that has happened. The Afghan government collapsed before Americans could withdraw from Kabul, inflicting a humiliation even more severe than our defeat in Vietnam. Iran’s rulers intuited correctly that they could get many of the concessions they wanted out of the administration without accepting even the gentle confines of the JCPOA. Vladimir Putin, who has always preferred to be in the driver’s seat, attacked Ukraine without provocation. Most recently, Iran’s proxy Hamas launched an attack on Israel, butchering and raping more than 1,200 innocent Israelis while broadcasting its savagery to the world. China has been too consumed by its own economic difficulties to take full advantage of the world crisis, but it is resolutely building up its military might and is poised to take advantage of any further American missteps.

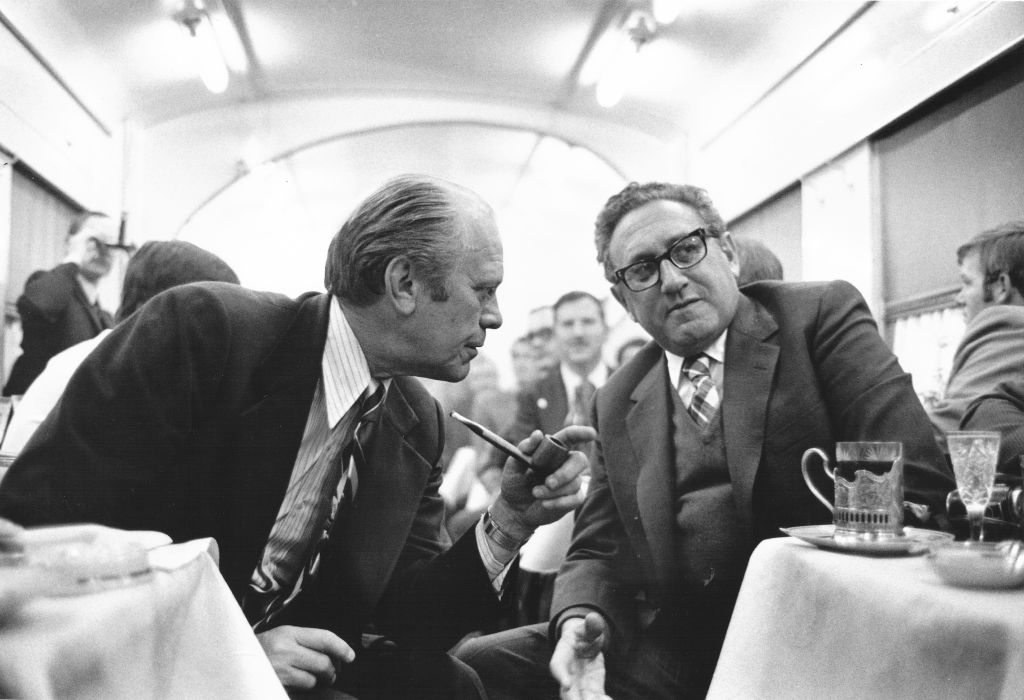

With America’s position in the world at its weakest since the 1970s, Henry Kissinger’s passing is a good time to examine how his career as national security adviser and secretary of state provides some important lessons for how the United States can get off the schneid today.

The United States was in bad shape when Richard Nixon entered the Oval Office in 1969 and made Kissinger his national security adviser. Rioters were burning down cities, bombings and assassinations were far too common, the American military was mired in a protracted slog in South Vietnam, and the Tet Offensive had shown that the Vietnamese Communists had more fight left in them than Washington had realized. Around the world, Soviet proxies were on the offensive, American conventional defense capabilities were overstretched, and the Soviet nuclear arsenal was on pace to exceed America’s, undermining the defense of free Europe. The American economy—the foundation of its power—was also eroding as Europe and Japan outgrew the favorable exchange rates America had extended to fuel their postwar recovery.

Nixon and Kissinger could not fix all of these problems, but their efforts went a long way to reverse American decline. Using some of their techniques could help lead us out of our predicament today.

Know what your adversaries want.

Of all his accomplishments in office, the opening to China is perhaps Kissinger’s most famous. After more than two decades of hostility and mistrust, the United States and China joined hands to deal with the Soviet Union. The idea of splitting Russia and China again has held a special place in American intellectual life over the past decade or so: It is both a hardy perennial in establishment organs like Foreign Affairs and a line that neophytes like Vivek Ramaswamy break out to display their supposed strategic acumen and independence from that foreign-policy establishment. Unfortunately, there is no prospect of repeating that masterstroke today.

The China maneuver was one of the most consequential of Nixon’s and Kissinger’s actions, but it was far from their most difficult feat. The two communist powers were already at odds: Their militaries fought each other a few weeks after Nixon’s inauguration, and Chinese leadership was terrified of a Soviet armored column advancing into China. Beijing was also chock full of doctrinaire Marxists who were always on the lookout for the final collapse of capitalism, and many there believed incorrectly that the Vietnam war showed that the United States had entered permanent decline. From their perspective, the Americans were a useful counter to Moscow, and since they would pose less of a threat in the future, there was little to fear from helping them. Kissinger might have been able to get better terms from Mao if he had pushed harder, but the Sino-American partnership still improved America’s global position.

Today’s circumstances are far different. Russia and China both see the United States as their top threat, and therefore are drawing closer together. Some in Beijing believed that the 2008 financial crisis and the election of Donald Trump presaged the final collapse of capitalism. But unlike during the Nixon era, no one in China fears Russia, leaving no chance of an opening. If Putin becomes convinced that the Chinese are winning and his fear of Chinese territorial expansion into Siberia outweighs his hatred of NATO, he might switch sides, but there is no indication today that he is willing to do so.

Kissinger was far from perfect, but in general he was a shrewd judge of what his foreign counterparts valued most highly and took advantage of their desires. By contrast, magical thinking about our adversaries predominates in the foreign-policy commentariat today.

Make adversaries bargain for what you want.

Kissinger’s signature policy was détente with the Soviet Union. To Jimmy Carter and other doves, this meant taking a softer line and looking to coexist; Kissinger’s version had a much harder edge. Although he tried to reduce bilateral tensions with the Soviets, the United States continued to frustrate its rival’s global ambitions. And the concessions he offered tended to benefit the United States.

Take arms control, for instance. Many hawks saw the Strategic Arms Limitations Talks as an unforced error. But the Soviet nuclear arsenal was expanding rapidly and coming close to matching America’s. Freezing the topline numbers of arms gave the Americans, whose missiles were generally more accurate, a quality advantage.

The Obama and Biden administrations largely get this backward: They make concessions that benefit our rivals. On climate change, they keep offering immediate cuts in American greenhouse gas emissions in exchange for vague promises that China will at some point in the future stop expanding its massive coal industry. Even worse, influential climate change advocates in both administrations have pressured their colleagues to soften their responses to Chinese bad behavior in other areas to keep these negotiations on track. Much of China depends on the Himalayan glaciers for freshwater, and the country as a whole is far more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than the United States is. China will benefit more immediately from carbon cuts that the United States will; American negotiators should act like it and stop sweetening the pot.

Kissinger’s formula was to offer the adversary something that also benefited his country; today it is the Chinese who follow that approach.

To gain more allies, defend the ones you have.

Expelling the Soviets from the Middle East was Kissinger’s most dramatic triumph in office. The United States had wanted to bring Egypt into its camp for decades, but longtime dictator Gamal Abdul Nasser preferred to work with the Soviets. Once Nasser died, his successor, Anwar el-Sadat, realized that the only route to regaining the Sinai Peninsula from Israel ran through Washington. Kissinger blocked every Soviet diplomatic foray in the region, but he overestimated Sadat’s patience. Eventually, Sadat joined hands with Syria to launch the Yom Kippur War.

While the Soviets resupplied the Arabs, Washington ensured that Israel had what it needed to fend off the attack without resorting to its nuclear arsenal. But once Israel blunted the Egyptian advance and its counterattack threatened to encircle and annihilate the Egyptian Third Army, Kissinger forced the Israelis to halt: If Sadat suffered a humiliating defeat, he might be replaced by a general who was a firm Soviet ally. Kissinger’s famous “shuttle diplomacy” eventually stopped the fighting, created a border settlement that Egypt and Syria respected, and robbed the Soviets of their most prized Middle East ally.

During the Yom Kippur war, the United States made sure its ally won, then restrained it to serve a larger strategic goal; in Ukraine and the Middle East, Biden is getting this backward. He has hemmed and hawed about dribbling in aid to Ukraine for fear of the Russian response. As a result, the United States and its allies have spent enormous sums to give the Ukrainians just enough not to lose, and the much-vaunted counteroffensive sputtered out. Then, after Israel was attacked, the administration made clear it did not want Jerusalem to retaliate against Iran, and it is restricting Israel’s own counteroffensive against Hamas. This will not do.

Kissinger found that American power and prestige increased when other countries realized they needed American support to win concessions from American allies. That happens only when our adversaries know that force cannot work against the United States and its allies. Today, our closest allies are questioning American leadership, and even countries like Saudi Arabia that have not yet been attacked are cozying up to our adversaries.

Op-ed pages have been filled with human rights-based condemnations of Kissinger, and hawks have long reviled détente and the peace deal that eventually led to South Vietnam’s conquest in 1975. Kissinger made his share of mistakes, but one thing his tenure teaches is that when your country is losing, the available options get worse and worse.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.