The Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) at the University of Pittsburgh is one of the country’s hubs for researchers working to improve detection and treatment for a disease that afflicts nearly 7 million Americans.

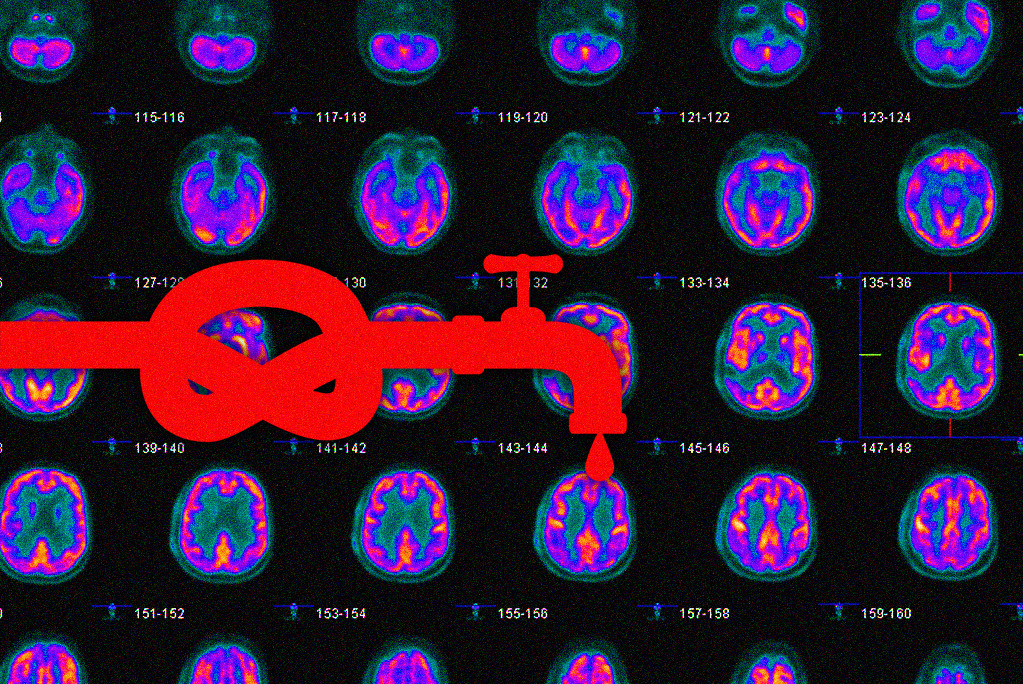

Anne Cohen—an ADRC faculty member who leads work on neuroimaging and identifying biomarkers of Alzheimer’s in patients—uses positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of research participants’ brains to work on the early detection of the disease before cognitive symptoms emerge. Cohen has been busy over the last two months, not with her own research, but trying to keep the ARDC open.

The ADRC, like the other 35 Alzheimer’s research centers across the country, relies on funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Cohen had counted on the arrival of funding from a five-year grant renewal submitted in June to the National Institute on Aging that was favorably evaluated, or “scored,” in the fall by a peer review committee. “The expectation was that we would continue to operate as our center always has,” Cohen told The Dispatch. But the federal dollars never came through, and Cohen and her colleagues are scrambling to retain staff while operating with less than a third of their normal budget—the center’s budget is typically $300,000 a month but is now operating at $115,000 a month from donated funds.

The center has had to stop all its PET imaging, which runs about $6,000 per participant. “Often our imaging contributes to the science; in symptomatic individuals, it can provide clarity and information about diagnosis, so those downstream effects of losing the ability to do this imaging on our participants has really been a challenge,” Cohen said.

After President Donald Trump took office in January, the NIH stopped meetings of review committees and the institutes’ advisory councils—the bodies responsible for the final approval of new research proposals and the extension of existing grants. Why the meetings were canceled and how long it would be before they were rescheduled has been unclear amid weeks of turmoil at NIH that have included the dismissal of probationary employees and high-profile resignations. The first advisory council meeting notice since the halt was published in the Federal Register on Thursday. As the delay dragged on, the NIH research funding pipeline largely ground to a halt, and biomedical labs are now running out of money to continue their work and pay researchers’ salaries.

The NIH, apparently working with Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), has canceled grants for projects officials deemed too closely tied to woke ideology and DEI efforts. (The DOGE X account periodically posts lists of individual grants canceled as part of this campaign.) In February, Trump administration officials at the Department of Health and Human Services directed NIH to cut billions in research dollars by imposing a cap on research grants’ indirect costs—overhead like facilities and administrative expenses—but a federal court temporarily blocked the move earlier this month.

In justifying the grant cancellations and the cost cap, the administration argued its actions would result in more money being spent on truly beneficial medical research rather than woke boondoggles or bureaucratic bloat. “The United States should have the best medical research in the world,” the NIH Office of the Director said in its February memo outlining the rate cut. “It is accordingly vital to ensure that as many funds as possible go towards direct scientific research costs rather than administrative overhead.”

But even as the administration put forward these arguments—something medical researchers and some former NIH officials strongly disagreed with—the canceling of advisory council meetings has frozen a reported $1.5 billion in research funds. The submitted grants were sought for all kinds of biomedical research, supporting not just indirect costs but all research costs and enabling work to continue on everything from Alzheimer’s disease to cancer treatments.

Although federal courts have blocked Trump officials from freezing federal funds, the administration has been able to cut off the funding pipeline using a bureaucratic workaround. New grants and proposals for renewed funding of ongoing research must be reviewed by study sections and approved by advisory councils. The study sections are made up of scientists from around the country and provide peer review for grant proposals, scoring each submission, and delivering written feedback to the researchers. After study section review, the top-scoring grants move forward to the appropriate advisory council, which provides a secondary review and final approval of the grants.

Jeremy Berg, an associate senior vice chancellor at the University of Pittsburgh Medical School and the former director of the National Institute of General Medicine Science, told The Dispatch that grants are legally required to be approved by the councils or else the money can’t go out the door. But in order for both the study sections and the councils to meet, notices of the meetings have to be posted in the Federal Register in accordance with legal requirements of the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA).

The Trump administration blocked the postings for the meetings. Berg said that based on his analysis of funding disbursement in February compared to the same period last year, the administration also has slow-walked an additional $1.8 billion in money for current grants that do not need study section or council reviews but are paid in annual installments and reviewed administratively each year to ensure compliance with grant conditions. The delay in disbursements is reportedly the result of confusion and fear among NIH staff about Trump officials’ directives potentially conflicting with court orders. Michael Lauer, the deputy director of the NIH office responsible for grant funding, was seemingly forced out of the agency in February the day after he sent a memo to NIH staff members directing them to resume grant disbursements.

“The fact that study sections were stopped dead in their tracks and not rescheduled puts the lie to the argument that it’s all being done in the name of more money for science,” Evan Morris, a radiology and biomedical imaging professor at Yale School of Medicine, told The Dispatch. “There ain’t no money coming right now.” Late last month, notices for study section meetings began to appear again in the Federal Register, and a new batch of them went up this week, along with the notice for a meeting of the National Advisory Council for Complementary and Integrative Health that went up Thursday.

Normally, advisory councils consider grants during three approval cycles each year, typically around February, May, and September. At this point, the delay has likely consumed two approval cycles, meaning the funding gap for already scored projects will continue for months—even if all council approvals resumed immediately—and will extend even longer for proposals yet to be reviewed by study sections. It’s common for proposals to receive promising scores from study sections but also feedback for improvement, requiring researchers to resubmit their proposals during the next review cycle. From a project’s conception to the actual disbursement of funds is almost always more than a year and frequently two years when accounting for resubmissions.

“We’ve made the assumption that even if everything got back on track tomorrow, we probably would not see funds until early summer, probably late May, early June,” Cohen told The Dispatch of the ADRC grant her center submitted last summer.

Cohen said the ADRC has shifted resources from research to staff retention, noting that if highly skilled staff members left, decades of institutional knowledge would leave with them. Many biomedical researchers, even faculty at universities, rely on federal grants for their salaries. She also emphasized the need to continue serving Alzheimer’s research participants. “These relationships have been built over almost 40 years, and stepping away from those I view as a breach of trust with the communities that we’ve committed to working with,” Cohen said.

The funding delay has severely disrupted ongoing research, but it also has stunted the progress of promising new research projects. Morris, the Yale researcher, is still waiting for a study section review of a grant proposal to expand a pilot study on the relationship between sleep deprivation and substance abuse. Morris explained that his research team believes they have observed, for the first time, a direct effect of poor sleep on the dopamine system. He said that if the findings are confirmed, they could have huge implications for everyone from psychiatrists to night shift workers to air traffic controllers. “But it’s a pilot study,” he added. “It was six men and six women, and it needs to be expanded.”

But with the NIH delay, he’s lost one researcher out of a team of four working directly on the project because he couldn’t guarantee a salary and another over a visa complication. There’s a limited pool of people who have the expertise to conduct the research, Morris explained. “It’s sort of like I have the World Series Red Sox from 2007 or 2018,” he said, “and then to find out that the whole team has been broken apart.”

Justin Perry, an immunologist and cancer biologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) Cancer Center in New York, is also experiencing disruption in work on a potential new treatment for breast cancer. Perry and his colleagues are trying to raise funds for a clinical trial on a treatment that could reprogram the body’s immune cells to use fructose to fight cancerous tumors. They submitted an NIH grant proposal for the trial that has yet to be reviewed. Perry also said that in the absence of NIH support, private investors have been reluctant to take on the financial risk of making up the funding gap, particularly given current broader economic uncertainty.

“I’m not going to sit here and say this is going to cost lives, because you just can’t prove that,” Perry said, noting his comments don’t necessarily represent the views of MSK. “It’s impossible to know if my work or my colleagues’ work is going to lead to the next treatment for breast cancer, but I do think that there are some significant dominoes that are falling in a bad way that we can’t rectify.”

Researchers hope the delay will soon come to an end with the confirmation of Trump’s nominee for NIH director, Dr. Jay Bhattacharya. He was asked during a Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee hearing earlier this month if he’d resume the advisory council meetings as soon as he’s confirmed. “Yes, if I’m confirmed, I want those advisory councils, all of that to go,” said Bhattacharya, who cleared the committee vote and is headed for a vote in the full Senate. But even if the grant pipeline restarts, the damage done to the rising generation of biomedical researchers could prove enduring.

Research universities across the country are slashing their graduate student admissions in reaction to both the funding delay and the uncertainty around future federal support with the administration’s move to cap indirect costs. Last week, the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School announced it would rescind all admissions offers to its biomedical science doctoral program for the 2025-26 academic year. Cohen told The Dispatch one of her biggest concerns is the harm that could be done to the next generation of Alzheimer’s researchers as early-career scientists, many of whom have had their first grant submissions bogged down by the delay, are now considering leaving the research sector. “It’s going to be a huge loss to science to see these folks go do other things,” she said. “I’m sure they will be fantastic at those other things, but it will be a loss to our field.”

The U.S. is currently the global leader in biomedical research, but geopolitical adversaries like China are close behind. “With the current turmoil, China could surpass the U.S. in the near future, and we may be buying advanced medicines and other scientific-research-intensive products from Chinese companies in the not too distant future,” David Baker, a University of Washington biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in chemistry last year, told the Wall Street Journal.

It’s unclear what policy goals a broad rollback in research funding would further aside from some relatively small reductions in federal spending. But even on cost savings grounds, it’s far from clear that slashing federal support would result in a net benefit, considering the volume of commercial patents and the economic value produced by NIH-funded research—in fiscal year 2024, $37 billion in NIH funding resulted in $94 billion in downstream economic activity.

There are good-faith arguments to be made about reforms to the NIH or the merits of specific research priorities—Bhattacharya would like to see the NIH tackle more ambitious, riskier research goals, for example. But the suspension of advisory council meetings combined with the Trump administration’s other efforts targeting medical research generally have thrown the system into chaos. “We have terrible treatments for breast cancer,” Perry told The Dispatch. “It’s the deadliest cancer in women, and yet, this all is affecting our ability to do that [research.]”

“Whenever I go home to Alaska and people learn what I do,” he added, “this is the thing that everyone wants the NIH to do.”

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.