Most efforts to protect kids from the harms of technology focus on delaying smartphones and social media for children and getting phones out of schools. As a tech policy expert, I fully endorse these solutions, but one key and often overlooked part of the equation is what parents must do about their own technology use.

You need only look around at a playground today to see it. Kids run around while their parents stare down at screens in their hands, oblivious to the noise, chaos, and needs of their children. Children tug on parents’ arms or scream for attention, and the parents often seem not to register it. At least not until the child throws a fit big enough to snap them back to reality. Maybe you’ve seen a playground like this one, or seen parents pushing a child in the stroller or through the grocery store, eyes glued to their phones. If we’re honest with ourselves, we’ve all been guilty of being this parent at one time or another.

While digital technologies’ addictive effects are more harmful to the developing brains of children, adults are not immune. Parents’ compulsive screen behaviors hurt kids. In fact, a relatively new field of research focuses on this problem, which researchers call “technoference”: the phenomenon of digital technology interfering with parent-child relationships.

Unsurprisingly, the results of this research so far are not good.

‘Technoference.’

Studies suggest that technoference negatively affects a child’s language learning, social and emotional development, and behavioral and emotional regulation, increasing attention-seeking behaviors, emotional outbursts, and rates of anxiety and withdrawal.

Take language learning. According to some experts, the children of adults who are frequently on their phones start school at a deficit, without the expected language or interpersonal skills for a 5-year-old. And children who attempt to engage with their parents but don’t get a response are less likely to initiate that interaction going forward—leading to the loss of critical learning opportunities.

These losses accumulate over time. Researchers explain that when phone use displaces parent-child verbal and nonverbal interactions, children receive less parental “scaffolding”—the just-adequate-enough support for a child to perform a new skill on his own—especially in developing their behavior regulation. The long-term result is a dysregulated child who struggles with behavioral difficulties, including tantrums, not being able to sit still, and getting easily frustrated.

Parents on phones are also less sensitive and responsive to their child’s bids for attention. And often, when children do manage to interrupt a parent, they are met with hostility rather than engagement and affection. One study found that parents are more likely to ignore children when using devices than when they are distracted with non-devices, whether reading a book or preparing a meal. Devices make parents uniquely less available—and that lack of attention can result in risky attention-seeking behavior in children. In other words, while handing a child a screen undermines their self-control, the parent staring down at a screen seems to have a similar effect.

Even babies feel the impact. When parents are looking down at a device, they are generally displaying a still face. This can distress an infant, because a still face—rather than an emoting one—displays a lack of attention, attention that infants rely on for their sense of security and emotional regulation. As a result, the infant will increasingly try to get the mother’s attention—and, if that fails, the infant will withdraw.

Likewise, with teens. One study from Brigham Young University’s Wheatley Institution found that “depression was higher in teens when their parents reported higher levels of personal social media use.” In fact, “adolescents are nearly four times as likely to be depressed if their parents are high level social media users.”

Babies, toddlers, children, and teens. All are negatively impacted by parental device use.

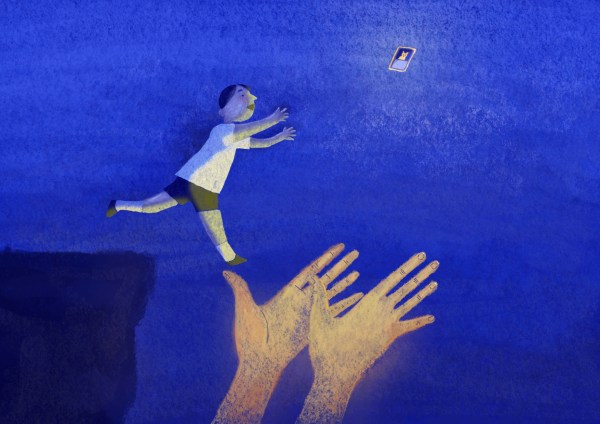

Perhaps most dangerous of all, however, is that the technology blinds its users to these negative effects. While we are staring down at our screens, we cannot see the little eyes watching us. We don’t notice the needs right in front of us—and we don’t notice that we are forming the desire in our children for screens, too. When we spend so much time looking at, scrolling, and texting on our phones, our kids will want to copy us—after all, children naturally want to do what adults do. My four-year-old wants to wash the dishes in the sink because he sees me washing the dishes and my two boys are always asking my husband when they will get to shave like Daddy. A Yale study found that young children, in fact, “over-imitate” adults, meaning that even when children are warned not to do what they see an adult doing, they are often unable to avoid reproducing those adult actions. This study is sobering when it comes to our phones. Even when we tell our children not to look at phones, if we don’t follow the same command, it will be extremely difficult for children to not imitate our behavior.

Forging a new relationship with our phones.

What, then, should parents do to free ourselves from the addictive pull of digital devices, so that we can reengage with our children?

We can start by separating ourselves from devices when kids are awake and we are with them. Have a designated phone box for your family so that at the end of the day, all phones go in the box and the family can be together without interruption. Place a basket near your door and put your phone in it when you come home and mute your phone and tablet so that you won’t be tempted by it. Inform your colleagues, friends, and family that you will not be responding to texts, calls, or emails for specific periods of time when you are with your children.

Try to live by the principle, “If I am with my children, then I am not on my phone.” Work to develop the skill of being mentally and emotionally present with your children instead. If they are young, get down on the floor and play with them, and involve them in what you are doing, whether in the kitchen or with chores. Make eye contact and engage them as much as possible. When you do need to do something on your phone while your children are present, resist the texting takeover of communication. Instead, try to make more voice calls, so they can hear you and know what you are doing. This also allows you to model good conversation skills for them.

You can also dumb down your phone, making it less appealing to pick up in the first place. Turn off notifications, put your phone in grayscale, and delete as many apps as possible, especially social media and other messaging apps. You can even take the internet browser off your phone entirely. If these changes sound daunting, you can always start smaller: Focus on identifying and eliminating at least one or two of the most tempting aspects of your phone for the long-term.

And, don’t be afraid to consider alternative phones to a smartphone. I made the switch two years ago, first to a Light phone and then more recently to a Wise phone, and while there are certain inconveniences, I don’t regret it for a second. I am freed from distraction and present for the things that matter.

Another step to remove yourself from the pull of tech is to establish rhythms of regular breaks from your phone, social media, the internet, and any digital technology. Consider a phone-free Saturday or Sunday as a family. Regular breaks will help restore a healthier relationship with technology. A recent study found that among adults who took a break from their smartphones by blocking the internet for just two weeks, 91 percent felt better after the break. “People had better mental health, better subjective well-being and better sustained attention,” says Adrian Ward, a psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin and one of the study’s authors.

Finally, taking regular breaks and being more physically distanced from our phones means going “old-fashioned” in our individual and family practices. Technology is always replacing something, so the best way to reduce tech dependence is to simply revert to the analog options. Have a family calendar on the wall. Use a notepad and pen to jot notes to yourself or to-do lists. Get an alarm clock for everyone to have next to their bed. Wear a real watch so that your phone isn’t your watch. Buy a family camera to use for pictures and videos so your phone isn’t your camera. Though these may feel like inconveniences in our fast-paced and hyperconnected world, you may find that returning to analog options benefits you and your family in ways you couldn’t have predicted.

Ultimately, by adopting practices to help us put our phones down, we model for our children what healthy technology use as an adult looks like—and open their eyes to the wonder of the world around them, away from screens.

Children will value what we value. Let’s show them we value people more than phones.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.