I remember an old man in white, alone in the rain. The memory is from March 2020, the height of the COVID pandemic. I remember his blessing, yes—the monstrance lifted above his head as he looked out onto the empty dark of St. Peter’s square—but mostly I remember how afraid I felt in those days. The clutch and flinch of it—not so different from now. And in the wake of fear comes the memory of his preaching. Not his words, really, but his voice. What I remember is the rush and swell and relief I felt. I remember his reverence for what we were enduring.

I remember Traditionis Custodes, the apostolic letter with which he restricted the celebration of the pre-conciliar Latin Mass. I don’t remember the letter itself, nor my own response, since I do not celebrate or attend Mass in that form. Instead, I remember my friends and their pain when reading it. Their voices. These are Catholics who had not only stood by Pope Francis and defended him to others, but who had worked to keep their own hearts open. They read his encyclicals, listened to his homilies, and tried to let him be a father to them. What I remember is how wounded and defeated they sounded, as though their efforts to be obedient had not only gone unseen and unappreciated, but were not considered obedience at all. How, they felt, could a pontiff look with mercy on so many and not find some mercy for them?

And I remember the crowded floor of the U.S. House of Representatives as he addressed a joint session of Congress in 2015. I remember how slowly he spoke and how thick his accent was. I remember how he said that every people has a gift to give, and then named four Americans who have helped us give ours: Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., Thomas Merton, and Dorothy Day. I remember feeling then like I’ve felt when someone whom I admire and who knows my heart—my mother, my spiritual director, a beloved older Jesuit—reminds me what they see in me, who I truly am. And I remember then-Speaker John Boehner, seated behind the pope’s left shoulder wearing a bright green tie, tears streaming down his face.

I’ve been asking others what they remember about Pope Francis—not what they think will happen in the long wake that will follow the end of his long papacy, but what their hearts will remember. This is because, for those of us who take the Incarnation of Christ to be a historical event and therefore do not take ourselves to be the prime movers of history, before we can step back and analyze what will come next and why, we need to root ourselves in something deeper. We have to try our best to notice how the prime mover is still moving. And this means remembering.

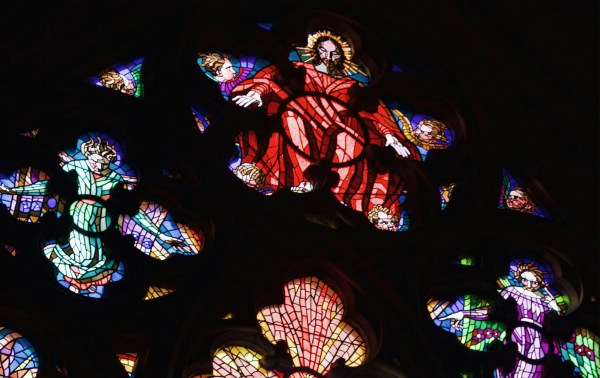

The site of our illumination.

This is not a new idea. Sixteen centuries ago, in his Confessions, none other than St. Augustine held that memory was the “bridge to the world outside ourselves, to ourselves, and to God.” It was “the site of our illumination.”

For Augustine this is because, in the words of historian Paula Fredriksen, the meaning of our lives “is distilled only retrospectively, through the integrative functioning of memory: it is only in recollection that the person can actually understand what he has experienced and see true meaning in it.”

So I have been asking people what they remember of Francis.

One remembers Lampedusa. Another Laudato Si, his encyclical calling us to care for creation as our home. One woman remembers a homily he gave in Ciudad Juárez on the U.S.-Mexico border in which he invited all those gathered to weep for injustice. “These are tears that lead to transformation, that soften the heart,” she remembers him saying. Many remember his first appearance on the balcony overlooking St. Peter’s Square, how he waved so awkwardly and how amazed they felt at being asked to pray for him.

Another friend, who is gay, remembers feeling shocked and even betrayed that Pope Francis spoke a gay slur not once but twice. A number of others remember how he knelt, on his bad knees, to kiss the feet of the warring leaders of South Sudan and begged them for peace. And one of my former students wrote to me that his local participation in the Synod on Synodality made him realize that “if the Church has to discern, so must I. If the Church has to work to listen, so must I. If the Church has to hope that it can find the will of Christ, so must I.”

Attending to what we are remembering can help us not only list but dwell in the themes of Francis’ pontificate: the poor, mercy, care for creation. Important as the memories themselves are, though, what may be more important is the habit of remembering together. That is, as Francis wrote, of learning to be “sensitive to the mystery of other persons.”

Memory and discernment.

To grasp the papacy of Pope Francis we need not just an analytic but a discerning attention. Put differently: I am distrustful of answers that step outside of time, that step away from the site of illumination. Instead I want a discerning answer because, like memory, it is old. Or, more accurately, it is traditional. It remains part of a conversation that is still going on, an argument that is happening now.

This kind of answer is hard to come by because, as 19th century theologian St. John Henry Newman wrote in An Essay On Development Of Christian Doctrine, it takes time for a “real idea” to reveal itself as itself in history. Contrary to our expectations, Newman argued that a great idea is not “clearest near the spring [but] purer, and stronger, when its bed has become deep, and broad, and full.” Like rocks in a tumbler, the most real of our ideas are only burnished by the sacred weapon of time.

We human beings tumble our greatest ideas about inside of traditions. As Alasdair MacIntyre has taught us in After Virtue, what we call a tradition is an “historically extended, socially embodied argument about the goods which constitute that tradition.” Living traditions, then, are ongoing conversations that take place over a long time.

And a tradition’s discerning answer, its “real idea,” arises from the collective attempt to listen deeply to how God has been speaking in the grammar of Francis’ pontificate just as he spoke in that of Benedict’s and John Paul’s. The discerning answer, in other words, is found by remembering the consolations and desolations that Pope Francis provoked, along with wounds we may have received or the healing balm he applied. The “real idea” is unearthed by remembering precisely these things and making them public.

Thinking traditionally about Pope Francis.

Learning this kind of “traditional” thinking and discerning attention is vital—I would even say nonnegotiable—as we try to take account of the papacy of Francis.

First, because it lowers the pressure. It reminds all those interested in his pontificate and the future of Catholicism and of whether we can live up to the ideals of equality and freedom and community from which our ancestors built our modern moral order that Francis has had neither the first nor the last word in this ongoing argument. Yes, his magnetic and surprising and disruptive papacy added a sentence or a paragraph or a page to that conversation, but it did not close the book. Nor did he want it to do so.

Second, it is because of this reminder that Francis is himself part of the tradition that we can ask better questions about what his papacy meant—how the paragraph his life and leadership added ought to be understood, and how it requires us to re-understand things we may have thought we already knew. Questions like this are animated neither by the fear that something has gone irretrievably wrong nor the conviction that Francis was so right as to have ended the conversation. Instead, they are motivated by another style of interest, one that tries to attend to how his inspiring, untidy, provocative leadership—full of imperfection and of grace—turned once more the rock tumbler of the Catholic tradition.

I am insisting upon this shift in style because instrumental analysis of the kind that stands back, often skeptically, in order to catalog the bonds and breakages between Francis and his predecessors can forget the central thing: that God too has been at work, shaping the conversation that is the tradition, through Francis’ papacy.

In seeing this we are doing our level best to be obedient to the example Francis gave us—we are learning from his ability to be “sensitive to the mystery of other persons.” It was not that Francis had some master plan for how to reconcile all of Catholic tradition with the individual rights, universal equality, and popular sovereignty that mark out the modern world. He did not know the outcome of the conversation he’s tried to facilitate. Which means that all the analytical and theoretical questions remain now that he’s gone, and they remain valid: How can a hierarchical church be reconciled with the equality of all? How can personal freedom be squared with regulated rituals and uniformity of doctrine? How can lay Catholics be expected to be public agents of their faith while not having a voting voice within their church?

The contribution that the papacy of Francis has made to these questions—the questions that for centuries have dominated the conversation that is the Catholic tradition—has been less an attempt to resolve them than to embody a practical hope: that the entire church might become a subject capable of being guided by the Holy Spirit. That it might become more and more fully the body of Christ that it already is.

I admit that there are many times when I am myself less hopeful than Francis was. I remember not only when I have been sensitive to the word God is speaking through the life of another, but also the other times when I have been insensate and self-centered. I remember how much it costs to be a good priest. Just as it costs much to be a good father, a good wife, a good friend.

What I will remember most about the papacy of Francis is how often he himself remembered not how hard such sensitivity can be, but how good it is. That is why, I think, he was less afraid than I often am. Pope Francis believed in time—which, as he often and cryptically said, is “greater than space.” He believed in taking time to listen and to remember. This would allow us to “work slowly but surely, without being obsessed with immediate results,” to “endure difficult and adverse situations,” and “accept the tension between fullness and limitation.”

The time to ask what comes next.

What is going to happen to the future of the Catholic Church?

It is a fool’s errand to predict, and not just because of the religious conviction that the Holy Spirit works through the papal conclave even if some in the conclave work for their own goals. It is also foolish in ways particular to our current situation.

Remember: When Francis was elected we had a collective sense of what the issues were that needed to be addressed. Now, we do not. In part that’s because Francis has radically diversified the cardinalate both geographically and existentially. Unlike previous centuries—or even previous decades—these are men who do not yet know one another. They lack a shared memory. It will take time for them to pay attention to their own memories of how God has been acting in them personally and in the people they serve, and to build memories of how God is acting in them together.

Surely, though, whomever is chosen will speak in a new voice, write a new page, turn the tumbler differently than Francis has. But all of this is just another opportunity to burnish the real idea, which, as Newman put it, feels its way forward over time. “From time to time,” he wrote, “it makes essays which fail, and are in consequence abandoned. It seems in suspense which way to go; it wavers, and at length strikes out in one definite direction. In time it enters upon strange territory; points of controversy alter their bearing; parties rise and fall around it; dangers and hopes appear in new relations; and old principles reappear under new forms. It changes with them in order to remain the same.”

We must remember this if we are to move forward in time, that is, to live together traditionally. And to do this we must remember the papacy of Francis rightly, ignoring neither the wounds it inflicted, nor those it left untended, nor the many—the many—it helped to heal.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.