On March 31, 1968, President Lyndon Johnson gave a national address on television from the Oval Office. After talking about taxes and especially Vietnam, he said: “With America’s sons in the fields far away, with America’s future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world’s hopes for peace in the balance every day, I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office.”

“Accordingly,” Johnson concluded, “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president.”

The announcement shocked the nation. Many praised the decision, including Republican Sen. Jacob Javits of New York, who stated, “in a grave hour of war and national doubt, the president has lifted the office of the president to its proper place, far above politics.”

Johnson’s proclamation came nearly four months earlier in the election cycle than President Joe Biden’s recent decision to withdraw from the 2024 race, but the two episodes—like the two men—share many commonalities, the chief one being that their vice presidents became the party standard bearers.

While Johnson insisted on following President Dwight Eisenhower’s tradition of avoiding an active partisan role in the presidential race in which he was not a participant, he at times couldn’t help himself, occasionally hindering Vice President Hubert Humphrey, his running mate in 1964 whom the Democrats eventually nominated as their presidential candidate in 1968. Biden, for his part, has not shown the same tendencies as Johnson and appears less likely to sabotage Kamala Harris’ candidacy. He is set to make a case for her at the Democratic National Convention on Monday night.

Biden will find himself in a similar position as LBJ once the convention in Chicago wraps up, in that he will seek to finalize some of his priorities before leaving office, from high-stakes negotiations like brokering a ceasefire in the war between Israel and Hamas to legacy plays like designating the site of a 1908 race riot in Illinois as a national monument. Biden’s agenda may occasionally bring him into conflict with Harris’ campaign, which, although made up of many former Biden staffers, now has different priorities.

LBJ hoped to focus on peace in Vietnam during the remainder of his lame-duck presidency, seeking to cement his legacy as a good president in difficult times. But seven months between his withdrawal from the race and Election Day proved to be some of the most contentious not just of his presidency, but the country’s history. Soon after Johnson announced his decision not to seek reelection, an assassin struck down Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee, igniting horrible race riots that engulfed the country and reached only a few blocks from the White House. It tested LBJ’s immense political skills to curtail the violence.

But the crises kept coming for Johnson as he devoted a great deal of time and energy to pushing the North and South Vietnamese to the bargaining table in Paris as the terrible fighting in southeast Asia continued to claim thousands of lives. An assassin killed Sen. Robert Kennedy, then a presidential candidate, in June, and Johnson experienced a major political defeat several weeks later when he sought to promote Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas to chief justice, a move eventually blocked in the Senate by Republicans. In August, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia, killing plans for a fall summit between LBJ and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev to discuss disarmament and easing global tensions.

LBJ remained a prominent player in politics throughout that pivotal summer of 1968, often proving remarkably skilled in guiding the country through turbulent waters. He refused to actively campaign for his vice president, and at times seemed outright hostile to Humphrey’s candidacy. He once publicly commented during the summer that his vice president “cries too much.” He said another time privately about seeing Eugene McCarthy and Humphrey holding crying babies: “That’s the way I feel when I look at the two candidates, like crying.”

Johnson would often bristle when Humphrey tried to assert his independence, especially relating to answering antiwar leaders’ calls for a halt to bombing in Vietnam and discussions of a withdrawal. While some historians have erroneously interpreted such comments as Johnson preferring Nixon to win the election that November, LBJ despised his eventual successor and never trusted him. It was his own vanity and thirst for power (and inability to let go of control) that often played a role in his actions as the election approached.

Such tensions went both ways, as Humphrey had to balance supporting the administration while also appealing to liberals and doves within the party—particularly when it came to Vietnam and Johnson’s supposedly slow decision-making process. “Nothing would bring the real peaceniks back to our side unless Hubert urinated on a portrait of Lyndon Johnson in Times Square before television,” observed Bill Connell, the manager of the 1968 DNC. “And then they’d say to him, ‘Why didn’t you do it before?’” Navigating these months—where Johnson was still president while Humphrey was campaigning—presented a real challenge for the two men and required a delicate balancing act.

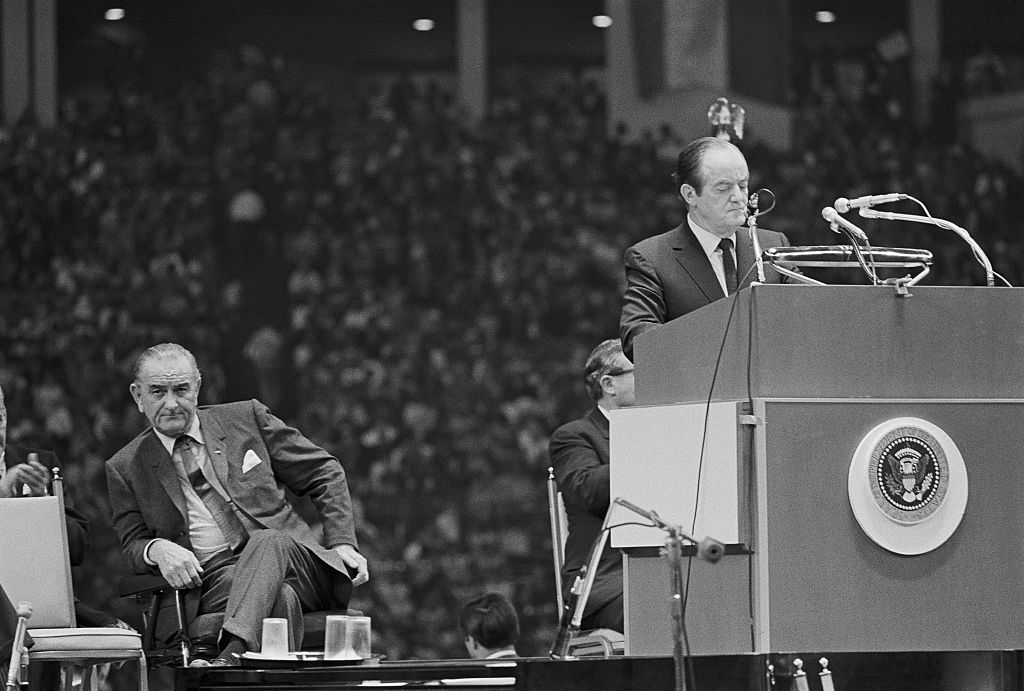

No event highlighted LBJ’s ambivalence more than the Democratic National Convention in Chicago at the end of August. The president’s loyalists maintained tight control of the agenda and events, and some pushed Johnson to consider visiting the convention on his birthday, August 27, with the possibility that he be drafted by the party to head the ticket once again. With Humphrey trailing Nixon by double digits in polls at that point, many people considered replacing him with LBJ or Edward Kennedy. But the call never came. His aides later insisted that Johnson never would have accepted, and that he only wanted the validation of being asked. However, his failure to fully support Humphrey in Chicago and the divisions in the party over Vietnam and the riots in the streets severely hampered Humphrey’s efforts coming out of the convention.

Into the fall, Johnson fought hard to push the combatants in Vietnam to come to the table for peace negotiations. He wanted to cement his legacy, of course, but deep down, he also wanted to help Humphrey despite their many disagreements. With patient and persistent pressure, the president neared a possible breakthrough in October, terrifying Nixon’s advisers, as the polling gap between the candidates had narrowed significantly since the convention and peace in Vietnam could put Humphrey over the top. Nixon himself reportedly told an aide to throw a “monkey wrench” in the peace talks, and the Nixon campaign, working through Anna Chennault and other GOP operatives, pressured the South Vietnamese to withdraw from negotiations by promising a better deal if Nixon became president.

With the race neck and neck, LBJ began publicly campaigning directly with his vice president in the final weeks of the campaign. He remained popular among many constituents, especially “blue dog” Democrats in the South. Another week might have changed the outcome, as Humphrey came within 500,000 votes of Nixon nationally after trailing badly for much of the race.

Many historians have wondered what might have happened had LBJ thrown his full weight behind Humphrey and his campaign earlier and more forcefully, but the president’s own vanity—as well as his efforts to avoid the appearance of partisanship in his drive to secure peace in Vietnam—stood in the way. The fact that Humphrey closed the gap as much as he did, however, underscores how small changes can affect an election’s outcome.

Harris may or may not win the election this November, but a lack of public support from Biden is unlikely to be a reason why. The president has already stepped back from the limelight in recent weeks after endorsing his vice president, allowing Harris to quickly consolidate the support of the Democratic Party and stand up a formidable general election campaign that is already polling ahead of Republican Donald Trump both nationally and in many key battleground states. According to NBC News, the president is expected to make a “forceful case” for Harris and Tim Walz, her running mate, in his convention speech on Monday night.

That dynamic could always shift, however, if the vice president’s campaign starts to struggle or she starts to break too much from the administration and its policies. As it’s commonly noted, 90 days is a long time in politics.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.