With the advent of the internet came the advent of discussion boards. And in the early 2000s, few subjects were as likely to end up locked by moderators as whether or not God was, in fact, dead.

On one side were the self-styled rationalists—your PZ Myerses, your Bill Mahers—arguing that religion was not just illogical, but outright deleterious. On the other, as popular memes had it, was “Jesusland,” arguing for things unseen, accused of burgeoning “theocracy” even as it unsuccessfully tried to “teach the controversy” over evolution in public school classrooms.

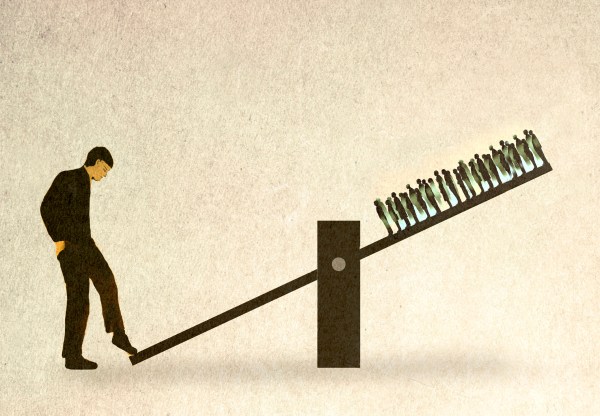

The army of unbelievers at the turn of the millennia was made up of autodidactic young men and embittered old ones; yet their passion couldn’t sustain their combativeness. Religion lost ground, yes, but without a foil, New Atheism slowly burned itself out. Today, irreligiousness is more prevalent but less contentious, more of a shrug than a statement, more “you do you” than “come at me, bro.”

In Believe: Why Everyone Should Be Religious, Ross Douthat seeks to reopen those debates. He offers a tour of theistic apologetics, exploring where various arguments that purport to show where science has disproved religion fall short. It’s an updated and cogent retelling of evidence that will be familiar to those who remember the old blogosphere arguments, from the existence of a finely tuned universe to the “resilience of the supernatural,” despite capital-S Science’s best efforts to eradicate it.

Believe engages with materialism on its own terms. Roughly the first half of the book deals with consciousness and the cosmos, from the start of the universe to the end of life. Science, far from disproving religion, has deepened it. “We have much better evidence for the proposition that the universe was made with human beings in mind…than ancient or medieval peoples ever did,” Douthat argues. Some who presume faith and reason are incompatible may well have their eyes opened.

From there, he guides the reader in how to think about the variety of spiritualities on offer, with an expansive, egalitarian argument for belief over apathy. And it’s this second half that seems more likely to wiggle its way into human hearts than the more abstract first chunk (I trust Mr. Douthat will not take it as a personal offense when I say his better half has a defter touch writing about scientific concepts than he does.)

Without quite fully lapsing into Huxley-esque perennialism—that is, the idea that every religion reflects different facets of a core truth, beneath cultural differences—Douthat argues that belief in anything is preferable to indifference. Even converting to the “wrong” belief system, he suggests, can rescue one from “the mire of meaningless and the snares of indecision.”

His book comes as in-your-face atheism is clearly a spent force; few could seriously argue that mass disaffiliation from religion has led to greater human flourishing overall. As such, Douthat works with the same tendency towards heterodox but vibrant spiritualism he identified in 2012’s Bad Religion and again in 2020’s The Decadent Society.

Based on his childhood exposure to various flavors of syncretism—a favorite childhood restaurant offered bookshelves packed with both crucifixes and astrological charts—Douthat is quick to point out the possibilities in our therapeutic, mix-and-match religious culture. The Gospel of Self-Help, or crystals for sale at the front of a Wiccan bookshop, may lead to self-delusion or worse, but they at least offer territory on which to have a conversation about the divine spark. More opportunity for heresy, yes; but also more opportunity for the numinous to break through.

That leads to his “case for commitment.” Rather than creating a pastiche of various “spiritual” practices, Douthat, a practicing Catholic, recommends “looking for wisdom in crowded places, in collective insights rather than individual ones, in traditions that have inspired entire civilizations, not temporary communities.” The last chapter, in which Douthat drops his attempt at religious egalitarianism to make an explicit pitch for Christianity, is the most rewarding. “Where there’s uncertainty,” he writes, “I make my bet on Jesus,” updating Pascal’s wager for the 21st century.

I, like many believers, am predisposed to find his arguments imminently plausible. If the book brings even one skeptic to seriously contemplate mortality, the project will have been worth it. Still, the conviction of the last chapter provides an intriguing hint of an even more persuasive book if Douthat had put his doctrinal cards on the table from the outset, rather than pocketing them in the interest of even-handedness. Perhaps a future director’s cut is in order.

But one inescapable question greets the publication of a book like this, no matter how thoughtfully written. As Douthat notes, part of what took the vinegar out of the Bush-era wars of religion is that many of that era’s fiercest critics ended up adopting a kind of grudging respect (or more) for Western Christianity as part of our cultural patrimony, particularly after their longtime foe had been brought low, partly due to self-inflicted scandals.

With church attendance falling, mainstream journalists are now safe to admit the decline has had negative social consequences. Polls show our decline in religion has slowed, but we remain a country in which the largest single denomination is “none,” many of whom aren’t hostile to religion; just uninterested. Religion isn’t necessary anymore; nor is it poisoning everything. It’s just nice, if that’s what you’re into.

In that sense, a book arguing it is good to go to church or mosque or synagogue, even if you don’t actually believe in the supernatural bits, would have been a trivially easy book for Douthat to write. Asking the reader to grapple with the claim that the spiritual, moral, and ethical claims of religion matter as much as, if not more than, the benefits community and fellowship provide, is a harder task. In a “spiritual but not religious” world, Douthat seems to be channeling C.S. Lewis, who said in 1952: “You can shut [Christ] up for a fool, you can spit at Him and kill Him as a demon; or you can fall at His feet and call Him Lord and God. But let us not come with any patronising nonsense about His being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.”

It may be that Believe is a bet on the future of religious revival coming not from the increasingly post-religious right, but the skeptics and Kabbalah-dabblers that make up America’s ruling class. More than that, though, it may be encouragement to his co-religionists, a nudge to get them to spend less time apologizing for their faith’s supernatural claims and more time making an apologia for them.

Indeed, many policy debates hinge on narrow protections of religious liberty, and religious leaders under siege sometimes look stuck defending their work as social service providers first, unable to pivot towards their deeper claims about truth and direction (some of their muddled witness is, of course, self-inflicted.) But Douthat wants these deep claims emphasized; he wants a faith unafraid to be weird, rather than boiling down pieties to fit on a bumper sticker.

Faith, by definition, requires belief in things that go beyond sheer reason. Vanishingly few will back their way into faith by deductive reasoning alone. But Douthat’s careful walk through how logic can complement faith is a boon for the health of American society—and the souls that comprise it.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.