Looking at the Thames but thinking of the Congo, Joseph Conrad’s Marlow observes to his fellow passengers aboard the Nellie: “And this also has been one of the dark places of the earth.” He could have been looking at the Mississippi, and the point would have remained the same: “The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much. What redeems it is the idea only.”

Some of our progressive friends would like us all to believe that the “real” history of the United States begins in 1619, with the arrival of the “different complexions” of first African slaves on what would later be U.S. soil. That is a critical and horrifying chapter in our national history, though African slavery in the Americas began in the 15th century under Spanish auspices rather than in the 17th century under those English privateers. As it turns out, this question is one of those things that tradition and conventional wisdom get right:

The story begins on December 21, 1620, when the Pilgrims first went ashore at Plymouth.

The Pilgrims were everything we are: immigrants, God-fearing radicals, and legalistic compact-makers of a practical bent, explorers, crackpots, idealists, capable of shocking brutality, instinctive capitalists, adventurers, irreconcilable, always eager to immanentize the eschaton, with one foot in the city on a hill they were building in the New World and one eye on the New Jerusalem they hoped to inhabit in the next. All the best and the worst of us is right there, at the beginning, on the Mayflower, these maniacs getting off of boats in Massachusetts in the dead of winter, these indigestible seeds coughed up by Europe, literally blown by the winds until they landed on just the right soil for the kind of seeds they were. It is too improbable a story to have made up. My friend Jay Nordlinger is fond of quoting George H.W. Bush’s question, whether our nation is to be a “unique nation with a special role in the world” or simply “another pleasant country on the U.N. roll call, somewhere between Albania and Zimbabwe.” Bush knew what he thought. (Jay knows, too.) And so did the Pilgrims, who had gone to such great literal lengths—about 3,000 nautical miles—to set themselves apart.

The Pilgrims were not known in their time as “pilgrims”—they were called Separatists and they were the Protestants of Protestantism, unable to go along and get along with the Church of England with its inevitable political accommodations. They had heard the call from Corinthians: “Come out from them and be separate.” And so that is what they did.

They had a kind of madness for novelty, and even the drama of exploring a continent that was entirely alien to them—the existence of which had been unknown to their people until fairly recently in their history—did not satisfy their appetite for newness. Soon enough, there wasn’t one colony but many, and many communities within each, many factions within those communities, divisions and rivalries and competition and, above all, innovation. Their descendants would spend much of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries inventing religions almost as zealously as they invented technologies and business strategies, adventures in capitalism going hand-in-hand with spiritual adventures and misadventures: River Brethren, Methodist Episcopal Church, dozens of Amish and Amish-adjacent sects, Seventh-day Adventists, Latter-day Saints, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Christian Scientists, Black Hebrew Israelites, Nation of Islam, Scientology, Branch Davidians, Jews for Jesus, People’s Temple, Church of Satan. Even the Polish National Catholic Church was founded in the United States—in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

In the Puritanism of that time (the Pilgrims were Puritans, but not all the Puritans were Pilgrims or Separatists), the dual nature of the later American character already can be seen: It is the combination of radical rejection with radical openness. The leading lights of Puritan New England were dreadful of excessive worldly entanglements but managed to make their peace with wealth and active acquisitiveness. (It is fitting that the great novel about the relentless pursuit of the meretricious was written by an English liberal and skeptic bearing the Puritan name William Makepeace Thackeray. Poor Becky Sharp could have been a proper American lady rather than a frustrated English social climber.)

We sometimes brag about our country being “exceptional,” but American exceptionalism goes all the way in both directions and goes hard: It is landing in Normandy to save the Europeans (again) from their own worst tendencies, the Rotary Club deciding to take the worldwide lead in the eradication of polio, Norman Borlaug helping the world become able to feed itself—and it is five dead at a massacre at a gay nightclub in Colorado Springs. We Americans know the Harry Lime theory of history: “In Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, and they had five hundred years of democracy and peace. And what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.” We Americans are a little bit of one and a little bit of the other: One day, we author the Declaration of Independence, and the next day, it’s the Fugitive Slave Act and Dred Scott. We are Dorothy Day and Timothy McVeigh, Abraham Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth.

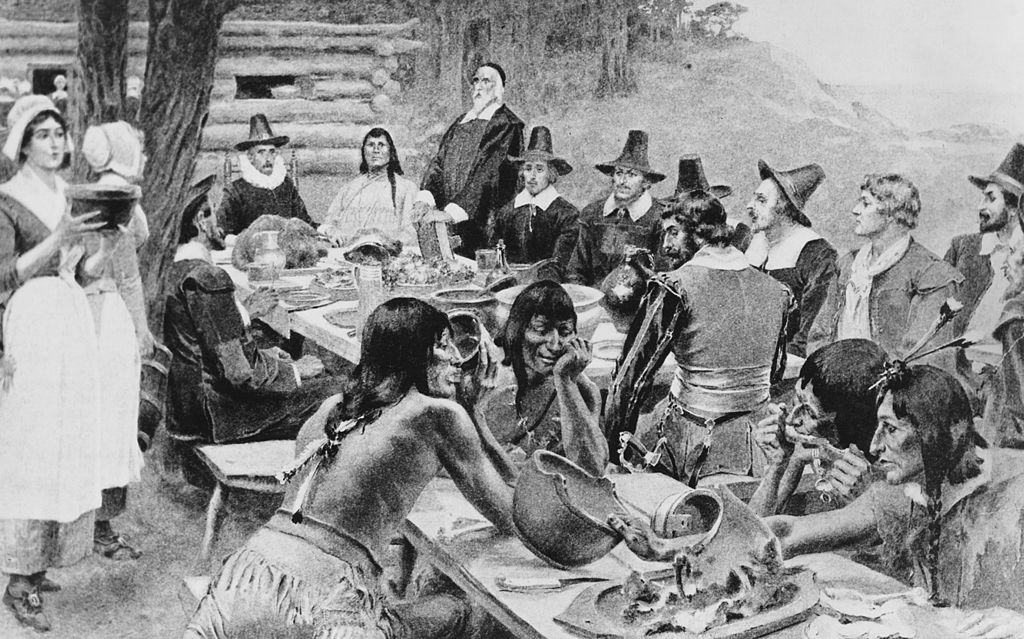

On Thanksgiving, we still think about the Pilgrims, who have otherwise receded from our national consciousness. But we ought to think more about them. We think of them as being linked to our cherished liberty, and they are, but they were not looking only for liberty—they wanted a world, and they found a place to make one. What they found was a “Second Nature,” as the writers put it in Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson:

And what was it for, this country?

The farms and the blood across the prairie?

The nation we become as we build a second nature.

The rivers run and parking lots the endless, endless fields and cities—

We make them, replace them with our dreams of the future.

And what was it for, the swimming pools?

The highways, the ballgames in the dusk?

And that is still the question: What is it for, this country, this “rendezvous with destiny” that Ronald Reagan spoke of:

We will preserve for our children this, the last best hope of man on earth, or we will sentence them to take the first step into a thousand years of darkness? If we fail, at least let our children and our children’s children say of us we justified our brief moment here. We did all that could be done.

It is to Providence that we owe the thanks we give on Thanksgiving, and the great treasure with which Providence has provided us with is not this continent, as rich and as magnificent as it is, but the great souls who have done the hard work—and who have at times done the dying—to hold off that darkness for one more generation, or, at times, for one more hour, mindful of the thousand years waiting on the other side of that hour. From the Mayflower to USS Nevada to Apollo 11—we climb inside, check the charts, say a prayer, and, like madmen—we go. Out there, beyond, to whatever is out there and whatever is next. Golf balls on the Moon? It is second nature to us. It is the going that matters most and defines us as Americans. It always has.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.