More than two centuries from the writing, Carl von Clausewitz’s On War remains the most certain guide to humanity’s most uncertain endeavor. Its salience has only been underscored by Russia’s renewed invasion of Ukraine. The war has seemed to defy predicted expectations, reminding us of the great Prussian’s observation that immeasurable moral elements can be more powerful than material calculations.

Yet in the realm of uncertainty and the interplay of factors that create the famous “fog of war”—of what Clausewitz preferred to call “friction,” to emphasize the role of human agency in contributing to the confusions—the Ukraine war has revealed some fuzzy but definite shapes. Ukraine, led by the unlikely but inspirational figure of Volodymyr Zelensky, has all but permanently secured its independence from Russia, as the repulse of the Russian assault on Kyiv demonstrated.

Denied this original strategic objective, and with their already-underperforming forces devastated, the Russians shifted their military operational focus eastward to the Donbas and southward to Mariupol and the rickety “land bridge” running east along the coast from Crimea. But, like the original invasion, this campaign has faltered from indecisive design, faulty planning, and insufficient and still-incompetent forces. Two weeks into the “Battle of the Donbas,” Russian attacks have ground to a standstill while what were initially local Ukrainian counterattacks have snowballed into something like a comprehensive counteroffensive thrust. It is still unlikely that the Ukrainians can deliver a war-winning blow, but they can shape the conflict toward that end. At the same time, a Ukrainian victory in the Donbas will create new strategic risks for Kyiv.

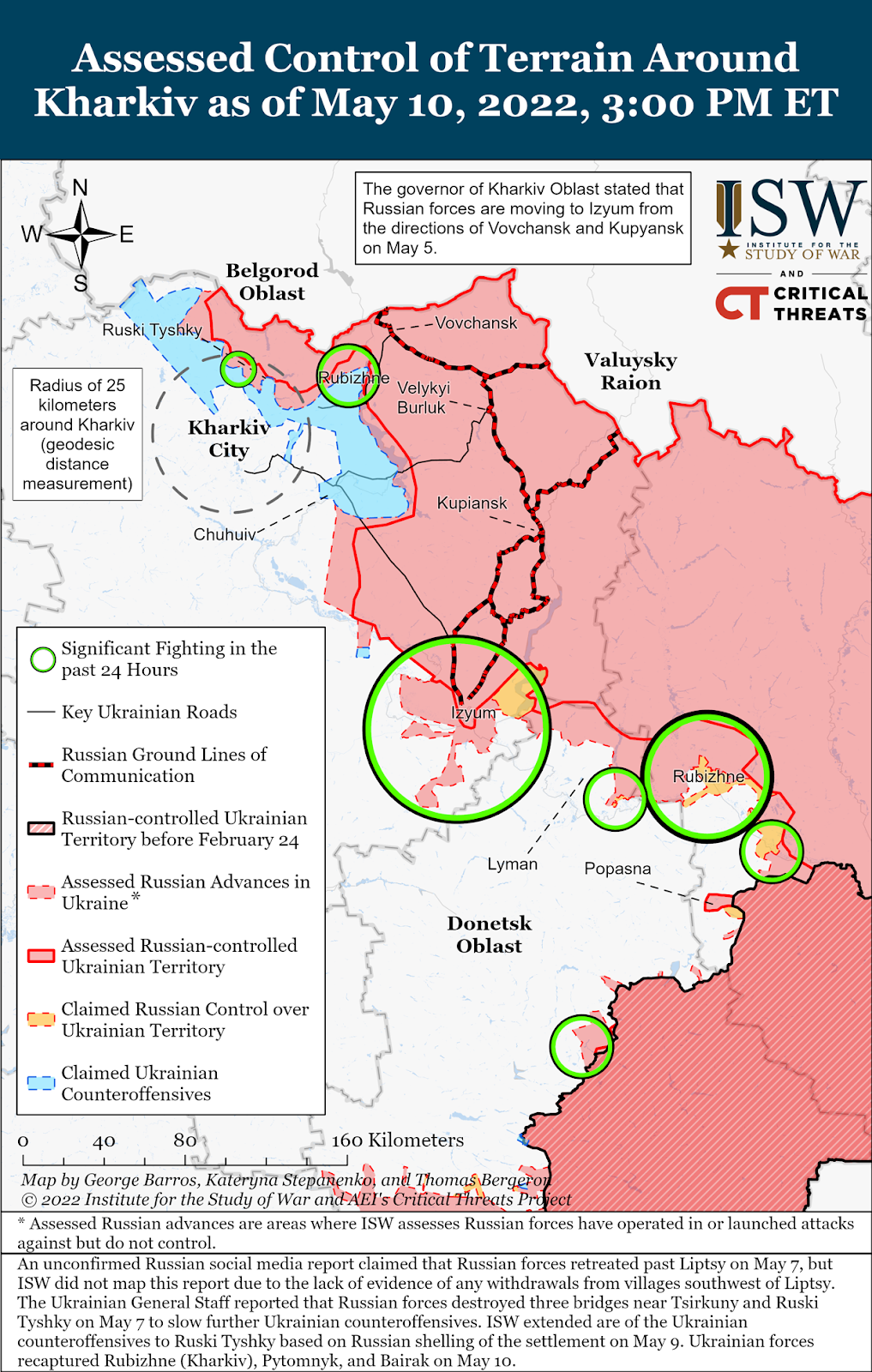

Let’s begin with a summary of the Donbas theater over the last several weeks. Upon withdrawing northward from Kyiv, Vladimir Putin gave his troops the shortest of pauses to lick their many wounds while calling up a small number of reinforcements. (At this point, as the astute analysts at the Institute for the Study of War have noted, counting the number of Russian “battalion tactical group” units became a near-useless metric; these were understrength formations to begin with, and many of them had been roughed up by the Ukrainians.) At the same time, Russian forces were heavily engaged in trying to reduce the Azovstal strongpoint in Mariupol—which, at this writing, they have not completed—and were still engaged, as they have been since 2014, along the “line of contact” in the eastern Donbas. The Russians never generated sufficient force to pursue so many avenues of attack and, after the failure before Kyiv and Kharkiv, had quite limited options for further maneuvering.

The Russians were also in a hurry; whether Putin ever felt the need for a “mission accomplished” banner for the traditional Russian Victory Day parade on May 9, it had become clear that the United States and its allies were now committed to backing the Ukrainians in a way and with armaments that he could not match. Thus the Russians began a thrust southward from bases around Belgorod, just over the border in Russia proper, down the east bank of the Siverski Donets basin through the Ukrainian town of Izyum; many speculated that the purpose was to envelop Ukrainian forces along the line of contact. But a substantial portion of the Russian forces committed to this offensive were those who had fought and lost in Kharkiv, and overall the weight of the attack—road-bound as ever—was neither great in the aggregate nor concentrated, but rather piecemeal. The Russians have advanced, at most, 15 miles from where they began two weeks ago, and, strung out along a limited road network, increasingly become prey for Ukrainian artillery.

Ukrainian forces have been equally active, and to greater effect. To begin with, they have quickly pushed the Russians back from Kharkiv to a point where they cannot continue the artillery barrages that had so destroyed parts of the city. Directly north of Kharkiv, it appears that the Ukrainians have reclaimed their territory to the international border. But two thrusts to the northeast and southeast promise to be more important militarily. The northeastern axis points toward the town of Rubizhne, where the river can be crossed to bring the Ukrainians less than 10 miles south of Vovchansk, through which runs one of the few railroad lines supporting Russian forces in the Donbas. Russian logistics are asthmatic at best, and the loss of Vovchansk could be asphyxiating.

And if that is not immediately so, the Ukrainian attack heading southeast from Kharkiv would choke off Russian supply lines comprehensively. Along this axis, Ukrainian forces have won back about 50 miles of ground. And they appear to be heading toward the town of Kupiansk, where all three of the major rail lines in the region converge. This would cut off the Russians’ Izyum attack almost entirely, threatening tens of thousands of Russian forces about 75 miles in their rear. In theory, they could try to escape by passing through Izyum, but the terrain east of there is more rugged and the road network much less developed. The conditions are present for a large-scale collapse of Russian forces.

To be sure, this is armchair analysis, but it reflects an operational logic that the Ukrainians have demonstrated and the Russians have not. Even if the Ukrainians have yet to show themselves capable of large-scale, longer-distance ground maneuver, they have clearly shown a powerful ability to rapidly mass accurate artillery fires on targets exposed by reconnaissance aircraft. And, now with the delivery and crew training of 90 longer-range U.S. howitzers with stocks of guided rounds, their capabilities are growing.

The tale of these two offensives—Russia’s thrust from Izyum and Ukraine’s east from Kharkiv—also confirmed that the Donbas campaigns are more about the armies than territory per se. As Vladimir Putin tacitly admitted in his perfunctory Victory Day speech, he is unable to bring further conventional forces to the fight, nor can he really shift around troops in an important way.

So what’s lurking around the corner of a Ukrainian triumph in the northern Donbas?

The view from Kyiv would surely be that this is a battle won but not the war, a giant first step toward securing independence and territorial integrity but still far short of “Ukraine whole and free.” But to claim that larger prize, the Ukrainians will need continued national willpower, more time, and further U.S. and European support.

At this point, Ukrainian will cannot be doubted; this is both an ancient nation reasserting itself and a new one being born. Ukrainians will define what victory is for them—and battlefield success can only expand that definition—and demand the time to win it. The question will be whether those who have supported the Ukrainians in their struggle will stay the same course.

The solidarity of Europe’s “Eastern Front”—those most threatened by Russian revanche—has been remarkable and is increasing. Poland, for all its domestic difficulties and anti-liberal backsliding, has emerged as a keystone to freedom’s frontier; likewise the Baltic states. The imminent applications of Finland and Sweden to join NATO represent a giant win for the strategic West and a catastrophic failure for Putin. To the southeast, Romania and Bulgaria have been solid citizens, as have Slovakia and Czechia in the center. Yet along this new borderland, there are soft spots—in the Balkans, and particularly in Viktor Orban’s Hungary.

The softest spots of all are to be found at the core of Western Europe, in Berlin and Paris. French President Emmanuel Macron, just reelected to a new five-year term of office, has, in recent days, reasserted a Gaulist truculence, declaring that it would be “decades” before Ukraine could be admitted to full membership of the European Union and that it was now essential not to “humiliate” Russia as Germany supposedly was after its defeat in World War I. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz appears to have been temporarily mollified by Kyiv’s apology for refusing to host a proposed visit by Germany’s president, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, previously an architect of Berlin’s policy of befriending Putin. Both countries helped to shape the so-called Minsk accords that froze the Donbas conflict after Russia’s first invasion in 2014, and are all but panting for a return to this status quo.

As much as ever, the course of the war depends in large measure on whether the Biden administration can translate its newfound muscularity into a longer-term commitment to Ukrainian victory. It has certainly seized the moment, and the Congress has swiftly passed—and even added to—its massive request for up to $40 billion in weapons and other aid to Kyiv. But as the fighting escalates it becomes more expensive; artillery and aircraft cost much more than manportable missiles. The Ukraine aid bill won a large, bipartisan majority, but with rampaging inflation and a host of other domestic troubles presaging a Republican majority come the fall midterms, the moment may not last.

Thus, the more Ukraine beats back the danger from the eastern front, the more it must look to secure its western rear. The silhouettes of war that seem apparent now may melt back into the fog.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.