Pete Buttigieg pleaded with last night’s debate audience in Las Vegas—and throughout the country—to see the light. “Let’s put forward somebody who’s actually a Democrat,” the former South Bend mayor said in a not-so-subtle shot at two of the frontrunners for his party’s presidential nomination. “We shouldn’t have to choose between one candidate who wants to burn this party down and another candidate who wants to buy this party out.”

Bernie Sanders told reporters in 2015 he was “the longest-serving independent in the history of the United States Congress,” and—while he has since formally affirmed membership in the party—he continues to exist well outside of its mainstream. According to reporting by Edward-Isaac Dovere in The Atlantic Wednesday, Sanders nearly mounted a primary challenge to President Obama in 2012. (A Sanders spokesman denied these claims.)

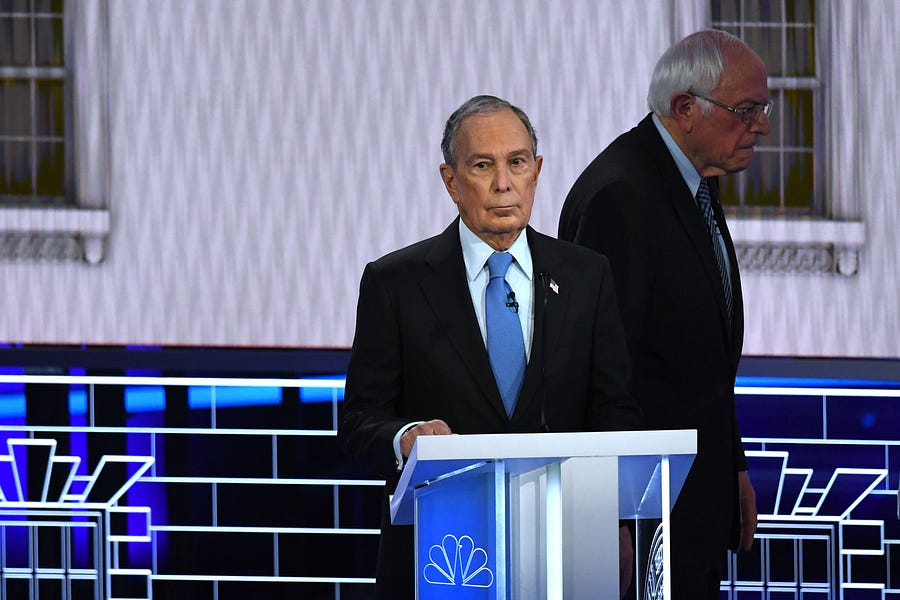

Also onstage Wednesday night was Mike Bloomberg, who—once a Democrat—successfully ran for mayor of New York as a Republican in 2001 and became a registered independent in 2007, only rejoining the Democratic party again in 2018.

On the other side of our political divide, today’s leader of the Republican party wasn’t one as recently as 2009. In a 2004 interview with Wolf Blitzer, for example, then-reality-game-show-host Donald Trump said he “probably identif[ies] more as a Democrat. … It just seems that the economy does better under the Democrats than the Republicans.”

For most of the 20th and early-21st century, Democratic and Republican presidential nominees devoted decades of their lives to the parties, toiling away at other levels of government and biding their time. Richard Nixon was first elected as a Republican to the House of Representatives in 1946; he later spent eight years as Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president before twice receiving the Republican nomination. John McCain spent nearly 30 years in the House and Senate—not to mention his several decades in the military—before being anointed the GOP standard bearer in 2008. Even Jimmy Carter, who at the time was considered the ultimate outsider, served in Georgia state politics for years—first as a state senator, then as governor—before winning the Democratic nomination in 1976.

No longer is that kind loyalty required. Jonathan Rauch—a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who has researched the parties extensively and written a book on the subject—helped explain why.

Rauch finds the Democratic party’s succumbing to Sanders—like the Republican party’s to Trump in 2016—a bit strange. “It’s proved difficult for the party establishment to coalesce behind a candidate, or to clear the lanes for a candidate, or to vet candidates,” he told The Dispatch. “And the result of that is this very peculiar fragmented campaign, which includes one person who’s not even a Democrat being the apparent frontrunner. That’s just bizarre.”

“The parties have lost a lot of their influence as organizations, even as partisanship and party brands have increased,” he said. “And the result of that is that you can be Donald Trump or Bernie Sanders, someone with weak or non-existent organizational ties to the party, but if you’re able to usurp the party brand—that is, use the party as a vehicle for yourself—you get all those voters because you’re running as the Republican or you’re running as the Democrat.”

But it’s not just Trump and Sanders that illustrate this phenomenon. The Democratic party stood powerless this past year as nearly 30 presidential candidates threw their hat in the ring, something Rauch deemed “ludicrous.”

“You had debates with 20 people, some of them not Democrats, and others, complete unknowns and opportunists,” he said. “I don’t know of any other country that does that, and it never happened in the United States before a few years ago.”

Rauch presented former South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg as an example of “someone who, back in the day would have been told, ‘so kid, go get yourself elected governor and then we’ll take a look.’”

A handful of factors have contributed to this reality. The rise of independent money allows outsider candidates to fund their races rather than rely on campaign contributions from the RNC or DNC. The deterioration of trust in media hinders journalists in their traditional gatekeeping role. An increasingly democratic primary process limits the ability of party insiders to hand-select nominees at conventions.

Rauch argued that while the smoke-filled rooms of yesteryear certainly had their problems, professional vetting from the parties “played a very, very important role in politics for which no other institution can substitute, including primaries.”

Supporters of both Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have complained in recent years that the respective party apparatuses were “rigged” against their preferred candidates. And they have a pretty good case. Few, if any, RNC staffers were rooting for Trump back in 2015 and early 2016; illegally hacked and leaked emails prove anti-Sanders sentiment ran rampant within the DNC during his first run for the White House.

But political parties are private entities, and, as Rauch notes, they are theoretically free to tip the scales whichever direction they please.

“The party is perfectly capable of saying, ‘Hey, you can’t be in the debate unless you’re a Democrat,’ meaning you have some record of working for the party, of donating to Democratic candidates, to campaigning for other Democratic candidates, having been elected to office as a Democrat. They can say that,” Rauch said. “They don’t, because they fear the backlash, but they could. And until very recently, people would have thought, ‘well of course they should.’”

Rauch described what he called the consumerist model of politics. “Candidates are like cereal,” he said. “We go to the supermarket, we find one we like, and we buy it, take it home with us. There’s no room in that model for intermediaries to do things like vet candidates, establish their track record to see if they’re a sociopath, and all the things that institutions do. But because of the consumerist model of politics, a lot of people think the parties actually add no value at all. That it’s simply a matter of, ‘I see a candidate, I like the candidate, the person says they’re a candidate, so I should have the opportunity to vote for them.’”

Occam’s razor would dictate the parties are susceptible to being co-opted by outsiders precisely because they have become derelict in their duties responding to voter interests and desires. The results of both the 2016 primaries and general election offered a sharp rebuke of the Washington consensus surrounding free trade, lax immigration enforcement, and interventionist foreign policy.

And parties rarely, if ever, had complete say over the outcome of a primary, even in those days of smoke-filled rooms. “It’s never been someone giving orders to the public,” Rauch said. It’s “always been a collaboration between party professionals and the public in this kind of consultative process.”

But in a recent Brookings report, he—alongside political science professor Raymond La Raja—concludes that current “presidential-nominating contests in both major political parties are at risk of producing nominees who aren’t competent to govern and/or don’t represent a majority of the party’s voters.”

“The parties’ and professionals’ confidence in their own legitimacy and efficacy has collapsed,” the pair write. “A self-fulfilling prophecy, and, as it turns out, a dangerous one.”

Rauch and La Raja lay out several reforms the parties can implement to take back some of this control they’ve forfeited: rank-choice voting, enhancing—not diminishing—the role of superdelegates, stricter debate qualification thresholds. But the most pivotal reform, they argue, is a change in mindset.

“Paradoxically, democracy fundamentalism—the insistence that the remedy for whatever ails democracy must be more democracy—is dangerously undemocratic, as America’s Founders well understood.”

Photo of Mike Bloomberg and Bernie Sanders by Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.