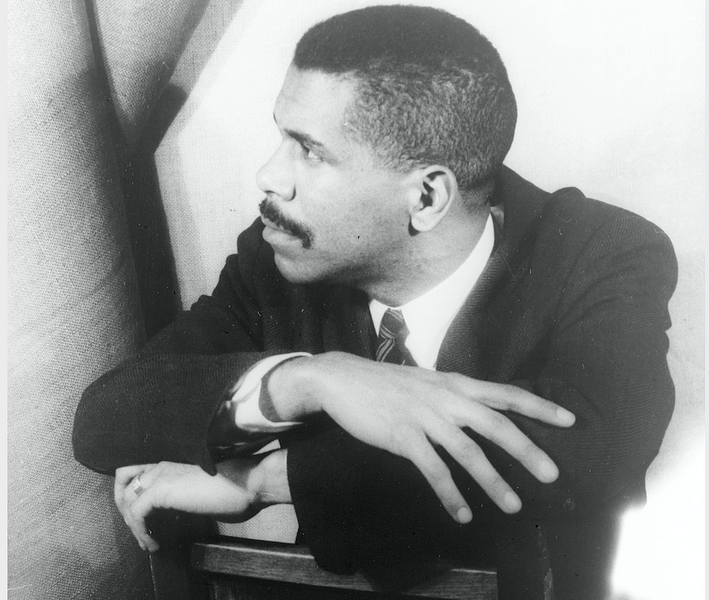

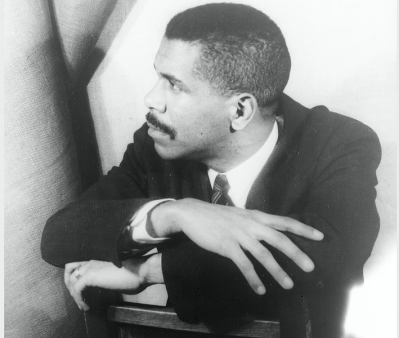

When in 2017 the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary added “woke” to their list of new words, they defined it as “alert to racial or social discrimination and injustice.” The earliest modern citation of “woke,” according to the OED, was a 1962 article, “If You’re Woke You Dig It,” written for the New York Times by the African American novelist William Melvin Kelley. Coincidentally, Kelley passed away the same year “woke” was recognized by the OED. In a 2018 profile of the late author, The New Yorker’s Kathryn Schulz drew her readers’ attention to the same Times article.

What neither the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary nor Schulz did, however, was provide a close reading of Kelley’s important essay, and as a result they lost an opportunity to dampen the culture wars now being waged in public and in private in the name of “woke.” “If You’re Woke You Dig It” is an essay that deserves rescue from the obscurity into which it fell for many years. But above all, it deserves to be seen for what it is—a work of cultural description rather than a battle cry.

I knew Kelley for many years as a Sarah Lawrence College faculty colleague. He enjoyed provoking readers with his fiction. His debut novel, A Different Drummer, published three weeks after his NYT essay, more than lives up to the title it borrows from Thoreau’s Walden. A Different Drummer tells the story of Tucker Caliban, a black farmer living in an imaginary Southern state who by his example persuades every African American living in the state to leave it.

By contrast, “If You’re Woke You Dig It” is not designed to set readers on edge. It’s an expository essay about the richness of black idiom that comes with a series of whimsical drawings that illustrate Kelley’s text. Written a year before the 1963 March on Washington, “If You’re Woke You Dig It” reflects its time (to the point where he uses the term “Negro”).

The essay begins with Kelley commenting on a New York City subway poster that advises train riders to keep the cars clean in 21 different “languages.” Among them is a variation telling train riders, “Hey cats this is your swinging-wheels, so dig it and keep it clean.” Kelly has no quarrel with the message. What he objects to is how the poster labels the message as “Beatnik.” Kelley’s point is that the language the New York Transit authority is calling Beatnik is really black idiom.

What follows is an account of the role in American life played by black idiom. “It is not only a language of vocabulary, but of context and inflection,” Kelley writes. Black idiom takes its meaning from those using it as well as those to whom they are speaking, Kelley argues. The language is constantly changing. The men and women using it take “pride in something that belongs completely to the Negro.” Whites who try to use black idiom, Kelley adds, are invariably going to be behind the learning curve, and for blacks that situation is, he acknowledges, often a source of pleasure. “The Negro’s pride in this idiom is that of a man who watches someone else do ineptly what he can do well.”

Kelley’s contention is not that the black idiom he describes can’t be widely appreciated. It translates well, he believes. “The American Negro feels he can, on the spur of the moment, create the most exciting language that exists in any English-speaking country today,” Kelley writes. Kelley even provides his non-black readers with an alphabetized lexicon that starts with “ace” and ends with “woof.” The entry for woke defines it as an adjective meaning “well-informed, up-to-date.” Nothing in the definition Kelley supplied suggests a code word for identity politics.

Kelley, who was just 24 when “If You’re Woke You Dig It” was published, saw himself taking the role of a friendly cultural guide in his essay, and he assumed goodwill on the part of his readers. He was not asking them to take an ideological stance but to attune themselves to a language filled with a complexity and wit they might not have fully grasped on their own.

Today, it is increasingly rare to see “woke” being used in a way that doesn’t reflect our racial divisions. Even the term’s defenders concede as much. In an op-ed headline “In Defense of Woke,” Damon Young, the author of What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker, notes that “woke” can no longer be said unironically. “What was a compliment just a few years ago has become, at best, an eye roll,” Young observes.

It’s worth revisiting “If You’re Woke You Dig It” to understand that for Kelley analyzing black culture also meant celebrating it. His essay doesn’t deserve to be burdened with our current cultural battles. The last thing Kelley imagined when he used “woke” in the title of his essay was that the word would be weaponized. If he can be faulted all these years later, it is for being too optimistic.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of literature at Sarah Lawrence College and author of Like a Holy Crusade: Mississippi 1964—The Turning of the Civil Rights Movement in America.

Photograph by Carl Van Vechten Collection/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.