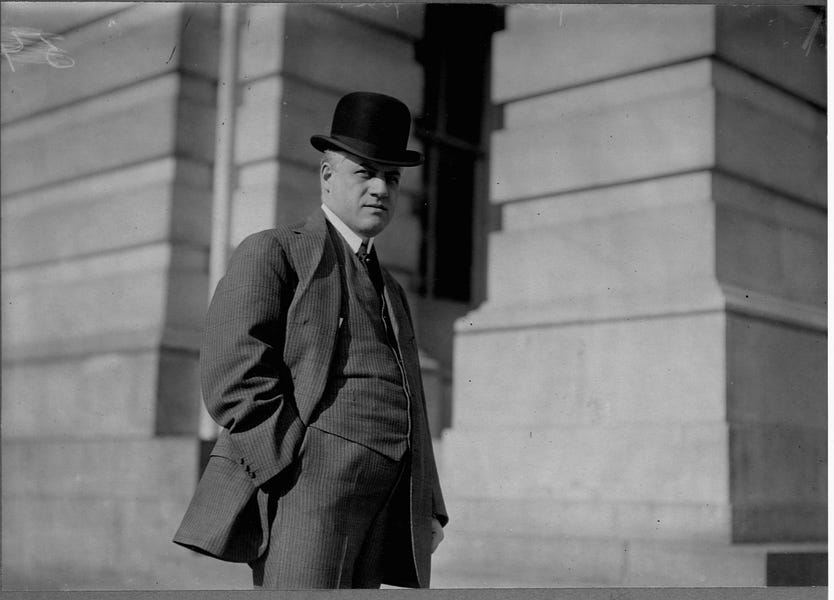

Mitchell Palmer would be worth knowing about even if his role in America’s past wasn’t so relevant to our present. Political history seldom affords us such a rank villain, and it is always the right time to remember the cautionary tale of a sanctimonious prig who becomes a thug with a badge.

Palmer hailed from Luzerne County, Pa., a place that in his lifetime (1872-1936) went from Quaker backcountry settled by families like his own to an industrial powerhouse thronged by immigrants from eastern and southern Europe. After Swarthmore and law school, Palmer climbed the ladder in the local Democratic Party, which was growing in power thanks to the immigrant boom. When he won a seat in Congress in 1908, Palmer was one of four Democrats in the Pennsylvania delegation. When he left the House six years later, he was one of 11.

Palmer was very much the Josh Hawley or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of his day. The young upstart elbowed his way into the 1912 Democratic convention and then used his post to help deliver the commonwealth’s delegates to progressive heartthrob Woodrow Wilson. When Wilson won in November, Palmer’s stock went through the roof. But he passed on Wilson’s offer to lead the War Department, instead opting for a Senate run. It proved a miscalculation. Palmer got trounced and found himself out of office and angling for various posts to maintain his clout.

By the time Wilson was re-elected in 1916 and managed to get the U.S. into the European war, Wilson had the perfect job for Palmer: to head the “Office of the Alien Property Custodian.” The job was to seize and either utilize for the war effort or liquidate not only any property of citizens of Germany or the other Central Powers but also Americans who fell under the administration’s suspicions. In some cases he installed his cronies in top positions at targeted firms, other times he just wiped out the businesses. Palmer got to lay siege to the Republican-leaning German-American community and got extra progressive brownie points because his crackdown on businessmen often meant busting breweries—a scourge of the left on the eve of Prohibition.

Asked if he saw any limits to his authority, Palmer declared “[war] power has no limits other than the extent of the emergency.” And he thought the emergency related to rich, Republican beer barons was very vast indeed. At the end of the war he claimed to have more than $17 billion in today’s dollars under his thumb.

When Attorney General Thomas Gregory retired after the war, Palmer was the natural fit. Appointing Palmer to succeed Gregory would bring political benefits to Wilson, too. Palmer was not only from the swing region of a target state, he was a favorite of the Democratic activist base, which saw Palmer as Wilson’s adviser Joseph Tumulty described him: “young, militant, progressive and fearless.”

Palmer took over the Justice Department in March 1919. Without the war, though, he didn’t have much of an excuse for the clapping of undesirables into leg irons and selling off their possessions. But as the Bolsheviks continued to grind down their opponents in the Russian Civil War, Western nations looked on in horror. Those fears appeared well-founded in the spring of 1919 when anarchists attempted bombings of top figures in business and government—including the one that nearly blew the porch off of Palmer’s home in D.C.’s Kalorama neighborhood.

In office only two months, the new attorney general was not only nearly a victim of the revolutionaries; he had a Congress feeling loads of political pressure from anxious constituents and eager to show results. Palmer quickly won the resources to form what would go on to become the FBI and recruited to run it a young lawyer who had also sharpened his skills chasing German sympathizers during the war: J. Edgar Hoover.

By the time Palmer and Hoover were done, thousands of suspected agitators and their families and associates had been rounded up and interrogated, including a number of American citizens. Dozens of foreign-born suspected radicals were deported with lots of enthusiastic press coverage. The “Palmer Raids” were deemed a mainstream success.

Early in 1920 and with that year’s presidential election very much in mind, Palmer, armed with reams of domestic intelligence from Hoover, predicted that the radicals intended to “on a certain day … rise up and destroy the government at one fell swoop.” The certain day was to be May 1—May Day—when communists and anarchists around the globe were said to be planning massive attacks. Palmer hadn’t been the bombers’ only target in the capital city the previous spring, and Washington braced for a more devastating version. But then … nothing happened.

The scaremongering that had resurrected his career and made him a very powerful man failed Palmer at just the wrong moment: The month before the Democratic National Convention would convene in San Francisco to pick a nominee. Palmer, who vied for the nomination, fizzled at the convention and would spend the last 16 years of his life a Democratic power broker, but never again a major player. History remembers him only for his goon squads, if that. Certainly the lesson his rise and fall can teach is lost on the aspiring Palmers of our time.

Today, our Capitol is hidden behind steel barricades and guarded by National Guard troops like an outpost in a hostile land. We heard last week about the warnings of an attack perhaps even more deliberate and dangerous than the pro-Trump mob that ransacked the building on Jan. 6. Congress canceled its Thursday session and the Capitol Police have asked the National Guard to stick around awhile longer to maintain the Green Zone on the Potomac. Meanwhile, modern Palmers in both parties seek more control over the flow of information to make sure that private companies don’t run afoul of speech codes.

The threats to the republic are just as real today as they were 99 years ago. There were real anarchist bombers and communist spies, just as there are real radicals on the nationalist right and social justice left willing to use violence to achieve their goals. But another threat is the same, too: Ambitious politicians eager to exploit legitimate fears to acquire and expand power. We should do our best to be mindful of both.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.