Lost in the play-by-play coverage of the Democrats’ internecine Build Back Better battles the past few months is how foreseeable their current debacle was. Not just because of Joe Manchin’s steadfastness, but another factor: a lot of Americans.

We were told repeatedly that Build Back Better was popular, but there was plenty of evidence that a good many Americans just weren’t as into it as much as President Biden and congressional Democrats believed. For instance, more than half of Americans told pollsters last summer that the child tax credit should not be made permanent, and despite more than 60 percent of survey respondents receiving the credit, only a quarter of them in October “strongly” supported expanding the policy. Twice as many independents oppose the idea of a permanent child credit than support it, and majorities across the political spectrum are uncomfortable expanding such benefits permanently without conditions such as work.

These data points are yet another expression of a growing problem on the left and right: the centrifugal pull of America’s political poles distorts the vision of the political class that sets agendas, covers politics, and spends too much time on Twitter.

They cannot see that most people dwell in an ideological heartland, removed at least a few steps from the febrile world of both the political class and the minority of Americans who comprise the splenetic, noisy grassroots.

The ideological heartland is filled with what we might call domestic realists. They don’t succumb to the centrifugal polar forces. They may sympathize with the tenets of the poles on a variety of hot-button issues, but they don’t want to go to war over them. They are comfortable with the idea that people can disagree and still live together peaceably. And they greatly outnumber the polar rabble rousers.

If you can imagine for a moment a third-party presidential candidate capable of winning a majority of electoral votes, the ideological heartland would be the reason why.

Domestic realists are not just the “exhausted majority” or whichever other appellation you prefer for centrists who are tired of the noisy extremes. They have priorities and commitments. They just want a politics scaled to their concerns rather than to the adrenalized anxieties of the politically obsessed.

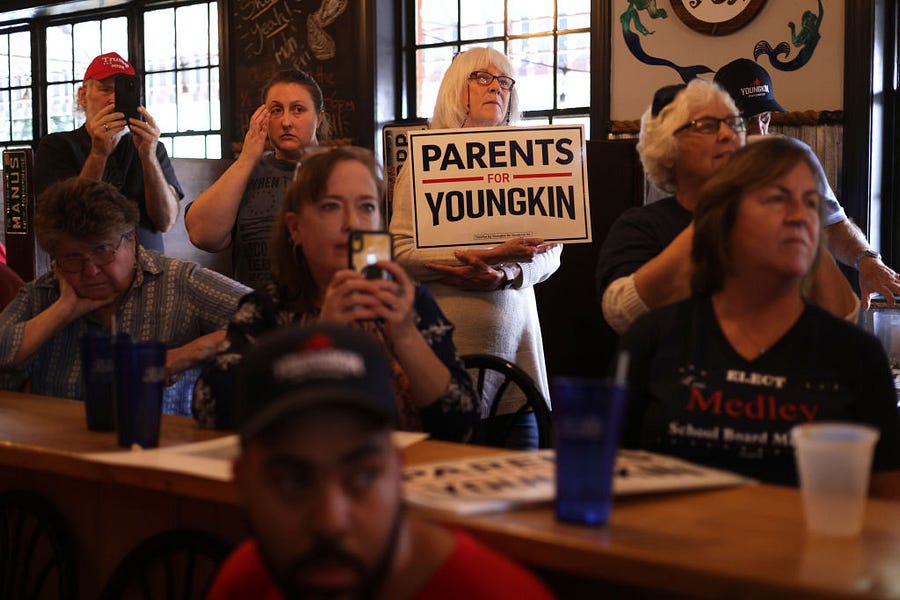

Domestic realists would rather hear politicians explain how they will take care of the basics, such as public safety, good schools, cost of living issues, and an environment conducive to good jobs and career options. They rate crime, taxes, and drugs as the biggest problems in their communities, far above politically charged issues like immigration or climate change. They are the Americans who kept the Build Back Better plan from being as popular as its supporters told us it was, the Virginians who elected Glenn Youngkin their next governor, and the urban residents across the country who were trying to tell their supercilious overlords 18 months ago that crime was their top concern. They are a majority of voters, and their motto these days might as well be, “We’re not stupid, y’all.”

Based on large national surveys at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), some telling fault lines emerge between domestic realists and those on the left and right with distorted polar vision.

Consider this: Committed progressives—people who say they are “very” liberal—are more likely to strongly favor changing the names of statues and street names than they are to support affirmative action, greater racial diversity in school districts, or more affordable housing. Fervent conservatives—those who are “very” conservative—are more likely than progressives to believe politics is a zero-sum game (that is, if one side wins, the other loses) and that individuals can make a difference in Washington, D.C.

That committed progressives care less about the situation of lower-income Americans than their culture-war battles, or that fervent conservatives have lost their sense of the properly-scaled relationship between the individual and the state, is no longer surprising to anyone paying attention to the breathless (and often mindless) “discourse” that passes for conventional wisdom these days. When you add national news consumption and how important people consider their political identity as factors in the survey data, the breathlessness only increases on both sides, leaving very little oxygen for clear thinking.

Committed progressives and fervent conservatives comprise only about a quarter of U.S. adults, while domestic realists—who lean right or left or say they are moderate—comprise about two-thirds of us. Domestic realists share with committed progressives and fervent conservatives a measured view of the future. Roughly a third of each group expect things in America to improve in five years and half expect things to stay the same. Slightly more than half of each group believe America’s best days are ahead.

But the groups quickly diverge in a number of important ways. For starters, 37 percent of domestic realists do not follow national politics closely, compared to 18 percent of those who say they are “very liberal” and 29 percent of those who are “very conservative.” Realists are the only group in which a majority believes liberals and conservatives have about the same amount of political power (people at the poles always believe the other side has more power).

On hot-button issues such as policing and immigration, domestic realists lean toward conservatives on the former and progressives on the latter, even though their position would generally be described as moderate in every case. Two-thirds of them oppose cutting police funding, compared to the 90 percent of fervent conservatives who are also opposed and the three-quarters of committed progressives who support defunding. Committed progressives are the only group in which a majority opposes more policing in their neighborhoods, while roughly 80 percent of both realists and fervent conservatives would like to see more police on their streets. Similar patterns exist in the levels of trust each group has in the police.

On the other hand, a modest majority (58 percent) of domestic realists oppose deporting immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally, compared to large majorities on the left and right on polar opposites on this issue. These data are consistent with other large national surveys showing that a majority of Americans—both native and foreign-born—want both modest levels of immigration and pathways for illegal immigrants to naturalize. Realists are, well, realists when it comes to thinking about the issue.

On racial diversity, they defy easy categorization. Fifty-five percent of realists support redrawing school district boundaries to increase racial diversity, compared to more than 8 in 10 progressives who support the policy and two-thirds of conservatives who oppose it. At the same time, 61 percent of realists oppose giving black people and other racial minorities preference in college admission, compared to 85 percent of conservatives who share their view and 76 percent of progressives who support affirmative action.

Especially notable in the survey data is intensity. Committed progressives and fervent conservatives are more likely to “strongly” favor or oppose any number of hot-button issues, whereas realists are more likely to simply favor or oppose something, but not “strongly” so. They simply don’t care as much about controversial issues as the polar crowd. This doesn’t mean domestic realists don’t have principles or strong views. They simply want issues scaled appropriately to what is most important.

For instance, more than half of them believe anyone can start a business and two-thirds believe they are living the American Dream or on their way to doing so, an optimism that outpaces progressives who are gloomier on both accounts. At the same time, 7 in 10 domestic realists favor adding affordable housing for lower income people in their communities, more than the roughly half of conservatives who think the same. They are also considerably more likely than not to believe that the economic system is rigged in favor of powerful interests. They are, on the one hand, optimistic that the little guy can make it in America, while on the other, concerned that it is harder than it should be due to the structure of our economy.

When it comes to views of government, majorities of committed progressives, fervent conservatives, and domestic realists distrust the federal government. Only 39 percent of realists trust the feds, compared to 47 percent of progressives and 20 percent of conservatives. But approximately 60 percent of all three groups trust local government. Once again, the political class in Washington—in both its left-wing progressive and right-wing national conservative varieties—has misinterpreted how most Americans think. The majority are not likely to want even views they agree with imposed on them and others from the nation’s capital.

For anyone who cares about the intersection of policymaking and politics, especially heading into an election year, it is important to note that “moderate” is a better moniker for a disposition than policy views. Domestic realists care about important issues and respond to agendas that focus on them. Their moderation has more to do with how they view the frenzied attachments around which our political poles are organized. If our political parties ever get around to learning this lesson, America will be the better for it.

Ryan Streeter is the director of domestic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.