For a long time, it was a truism that being mayor of New York was a dead-end job. Only two mayors had ever achieved higher office—the last time it happened was when John T. Hoffman was elected New York governor in 1868. The presidential campaigns of John Lindsay in 1972 and Rudy Giuliani in 2008 both crashed and burned in embarrassing style. The same fate that befell Mayor Bill de Blasio’s anemic 2020 presidential campaign seemed only to confirm the long-held political wisdom that New York politics just don’t seem to play nationally.

If that is the case, why then does it appear likely that this year’s presidential election will come down to a contest between two very different New Yorkers: Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders? Sanders, a Brooklyn native, leads national polling and most of the Super Tuesday states. And Super Tuesday is interesting for another reason: It’s the first time Michael Bloomberg will appear on any ballots. If Sanders is unable to secure the Democratic nomination, Bloomberg could well become the Democratic standard bearer. If that’s how the race develops come the fall, Americans will endure a presidential campaign whose roots lay in Gotham’s bitter politics over the last six or seven decades.

A partial explanation for this shift is that New York no longer stands as a bogeyman for the rest of America. Its mix of hyper-capitalism and socially liberal multiculturalism is far less of an outlier in today’s America. New York’s evolution from the city of Charles Bronson’s Death Wish to a Disney-fied Times Square helped soften the city’s image nationally and 9/11 garnered sympathy for the city from most of American society, even those who can’t stand cities.

But there is another explanation for this year’s presidential campaign. Our current political divisions owe much to the politics that formed in New York during the 1960s and 1970s. Under Mayor John Lindsay, liberalism in New York politics began to break down along a top-down coalition of affluent, liberal whites who lived in Manhattan and the nicer parts of the Bronx and Brooklyn and their allies in the black and Puerto Rican communities versus middle and working class white New Yorkers in the outer boroughs.

This is the New York of Tom Wolfe’s Radical Chic, which did so much to embarrass the faux-radicalism of so many elite New Yorkers at the time. Racial politics played a role in the divide, but the outer borough, blue-collar whites also believed that better educated, elite New Yorkers were dismissive of their concerns and pursued policies that sacrificed their interests for the sake of social justice. Sound familiar? Since Trump’s election, pundits have been obsessing over the rightward drift of “working-class whites,” but miss the fact that the roots of that phenomenon can be seen in the city’s politics of the last 50 years. Instead of bridge-and-tunnel vs. Manhattan, today we have a rural vs. urban/suburban split and a college-educated vs. non-college degree divide on a national level.

Trump has internalized this style of New York politics and appeals to working-class Americans who feel betrayed by elites of both parties. It is part of his own outer-borough background. Though he inherited his wealth, Trump has always seen himself as an outsider in Manhattan. It is also no coincidence that the mayor who best represented this conservative urban coalition in New York and presided over the dramatic rebirth of the city during the 1990s – Rudy Giuliani – is, for better or worse, Trump’s most dogged public defender.

With Reagan and Giuliani and the fall of Soviet communism, many American believed that by the 1990s, far left politics in America had fallen into the dustbin of history. As is often the case, though, history has managed to bite back under the geriatric Marxism of Bernie Sanders. Although having lived in Vermont for much of his adult life, Sanders’s politics are rooted in a long tradition of his native New York’s radicalism. In Historian Maurice Isserman wrote in the New York Times in 2017: “For a few decades—from the 1930s until Communism’s demise as an effective political force in the 1950s—New York City was the one place where American communists came close to enjoying the status of a mass movement.” Even in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Giuliani’s two victories as mayor came against Democratic politicians who belonged to the Democratic Socialists of America.

So left-wing politics never quite died in New York and has been resuscitated by a wave of millennial and Gen Z gentrifiers transforming not just New York, but cities from Boston to San Francisco. It’s no surprise that one of Sanders’s most energetic surrogates is New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the “La Pasionaria” of the modern American Left and symbol of this new progressive urban politics. Add to that another Sanders surrogate, current Mayor Bill de Blasio, a red-diaper baby who thinks there is “plenty of money in this city. It’s just in the wrong hands.”

For his part, Bloomberg (by way of Medford, Massachusetts) represents contemporary “neo-liberalism”—an unfortunately ubiquitous term among academics that basically means a liberal who doesn’t hate capitalism. (Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer also fits into this category.) Bloomberg was elected basically as Rudy Giuliani’s third term. Many of his policies challenged liberal shibboleths, from fiscal policy to policing to education reform. Much as Bloomberg is trying to save the Democratic Party today from the disaster of a socialist capture of the party, Bloomberg’s mayoralty was an attempt to bring liberalism into accommodation with the realities of post-1975 New York. Democrats like former Gov. Hugh Carey and former Mayor Ed Koch helped steered the city away from the brink of bankruptcy and toward fiscal stability and in doing so helped marginalize left-wing politics. Following their lead and that of Giuliani, Bloomberg would continue down that road.

That near-bankruptcy along with rising crime rates helped pave the way for a national rightward shift that culminated in Reagan’s election in 1980. Since the 1960s, New York politics have had a subtle, but deep, influence on our national politics. Now in 2020, those trends have broken out in this year’s presidential race.

It is doubtful whether this potential all-New-York presidential campaign will foreshadow the dominance of New York politics moving forward. Trump is sui generis and unlikely to be replicated; Sanders’s socialism is still too far out of the mainstream even for many in his party; and Bloomberg’s technocratic neo-liberalism is as cold and charmless as the billionaire himself.

In the meantime, Americans living in that great wilderness beyond the Hudson River will most likely have to endure a presidential race fought within a political framework forged in the sidewalks of New York over the last 50 years.

Vincent J. Cannato teaches history at the University of Massachusetts Boston and is the author of The Ungovernable City: John Lindsay and his Struggle to Save New York.

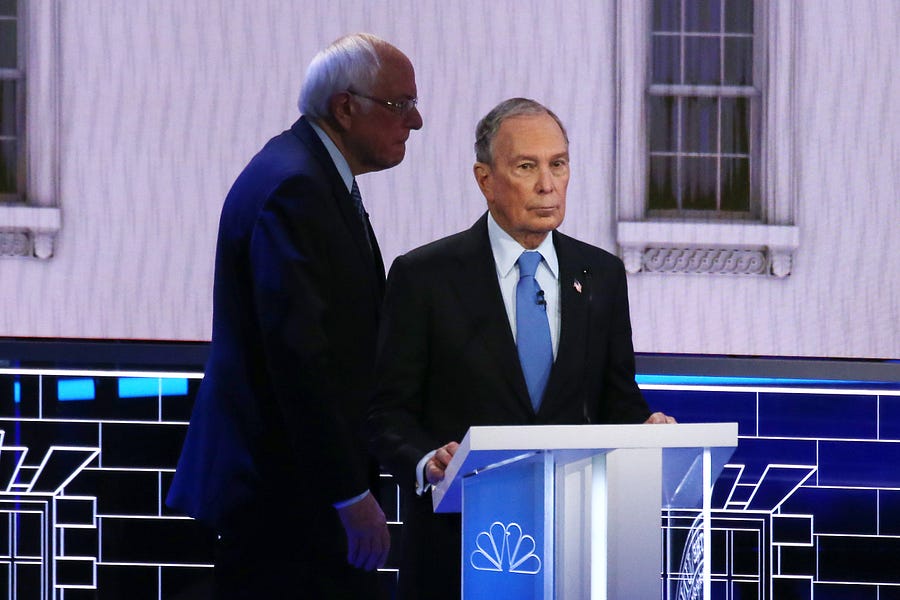

Photograph of Michael Bloomberg with Bernie Sanders in the background by Mario Tama/Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.