In early June 2020, an unnamed state actor (spoiler alert: China) launched a wide-ranging cyber-attack on Australian “government, industry, political organizations, education, health, essential service providers and operators of other critical infrastructure,” per Prime Minister Scott Morrison. The assault was only the most brazen in a series of escalating Chinese attacks on Australia for what was perceived in Beijing as insufficient obeisance to Chinese Community party dictates about everything from coronavirus to Hong Kong.

The proximate cause of China’s increasingly hysterical treatment of Australia was an April statement by Morrison calling for an international inquiry into the origins of the coronavirus: “This is a virus that has taken more than 200,000 lives across the world. It has shut down the global economy. The implications and impacts of this are extraordinary. Now, it would seem entirely reasonable and sensible that the world would want to have an independent assessment of how this all occurred, so we can learn the lessons and prevent it from happening again.”

The PRC official response began with relatively anodyne insults. Hu Xijin, the editor of state mouthpiece Global Times, wrote on the Chinese social media platform Weibo that, “Somehow Australia is jumping up and down again and again. It is like chewing gum stuck to the bottom of China’s shoe. Sometimes you just have to find a rock and rub it off.” An editorial in the Global Times also went after Australia for “panda bashing.” Previous such jabs have resulted in sheepish walkbacks from Canberra, a recognition that Australia’s economy is heavily dependent on China for its continued prosperity. How dependent?

In 2018, exports to China accounted for more than 32 percent of Australia’s total, twice as much as its second largest trading partner. The PRC buys a full two-thirds of Australian barley shipments, worth about $1 billion U.S. annually. It buys 24 percent of Australian beef, worth almost $2 billion. (And those are just the tip of the iceberg: China buys almost two-thirds of iron ore exports, almost half of coal exports, and 40 percent of liquid natural gas exports.) There were 260,000 Chinese students studying in Australian high schools and universities. That’s twice as many as the next group of international students (Indians). What are education exports worth to Oz? More than $25 billion, of which China represents a major chunk. Chinese tourists to Australia annually? Almost 1.5million visitors annually (about 15 percent of the total, and the highest number visitors to Australia), worth a staggering $8.2 billion.

In short, the Australian economy, more than most, is profoundly dependent on China. And this lack of diversification has been its Achilles heel in dealing with pressure from Beijing. But Australians are tiring of being bullied, which is, at least in part, why Xi has upped the ante. On May 12, China slapped a ban on exports from four Australian abattoirs, blocking about 35 percent of beef exports to the PRC. Six days later, Beijing escalated with an 80 percent tariff on Australian barley. Nor are Australians in China safe: An Australian national arrested seven years ago for drug trafficking into the PRC was suddenly sentenced to death in early June.

June also brought a travel warning about the dangers to Chinese tourists visiting Australia and a cancellation of organized tours. Coronavirus? Nope: The Chinese Ministry of Culture and Tourism sounded the alarm about a “significant increase” in “racist attacks on Chinese and Asian people.” On its heels came a warning for Chinese students studying in Australia: The Chinese education ministry reminded “overseas students to conduct a good risk assessment and be cautious about choosing to go to Australia or return to Australia to study” because of “racist incidents.”

These are not mere cautions rooted in concern for the well-being of Chinese nationals, similar to the travel warnings sometimes issued by the U.S. and other governments. These kinds of warnings from the Chinese government more resemble diktat than advice; a political spat with South Korea over the deployment of American anti-missiles systems in 2017 resulted in similar travel and education warnings, costing South Korea’s economy about $15.6 billion, with a staggering nosedive of 48.3 percent in Chinese tourists. So the implications for Australia are clear.

Why does this tempest in Oceania matter here in America? After all, the United States remains the dominant economic player on the global stage, far less prey to Chinese bullying. And, Beijing points out enthusiastically, the United States also levies sanctions against countries in non-compliance with standards often set in Washington. But these are apples and oranges. Chinese sanctions against Australia in this instance relate to the completely acceptable demand that the roots of a pandemic be investigated.

Beijing’s anger with Canada over the potential extradition of a Chinese national to the United States, to pick another example, resulted in the arrest of two Canadian NGO workers on false charges, with the clear intention of holding them hostage until Canada is prepared to agree to a prisoner exchange. To ratchet up the pressure, the two Canadians were charged last week with spying. In other words, Chinese actions are neither proportional nor consonant with rule of law. Rather, they are the actions of an autocratic government that feels empowered to treat foreign countries and their citizens as arbitrarily as it treats its own citizens.

And that’s the point of the Australia-Chinese saga—China is the second most dominant global economic player, and while it has trouble kicking up, it has no trouble kicking down. What is happening to Australia is a harbinger of dramatic escalation by the Beijing government, not just vis a vis Canberra, but European nations seeking post-COVID diversification away from Chinese supply chains, Asian nations seeking security assurances from the United States, not to speak of all those who have willingly walked into the Chinese debt trap that is its Belt and Road Initiative.

What to do? Capitulation, as has been the case since time immemorial, will only wedge Australia more firmly under Beijing’s heel. The right course is for Canberra to seek other export markets, and to look to its Pacific neighbors and its friends in the United States and Europe for support against Chinese bullying. There is, after all, a global market in the commodities that Australia exports, iron ore in particular. It is not imperative to the People’s Republic. China is used to seeing countries like Australia knuckling under in response to pressure. It’s time for Australia and its neighbors to branch off the road to perdition that is hyper-dependence on the People’s Republic of China and to create economic, security, and cultural partnerships with neighbors and like-minded friends that bypass and begin to isolate the Xi Jinping regime.

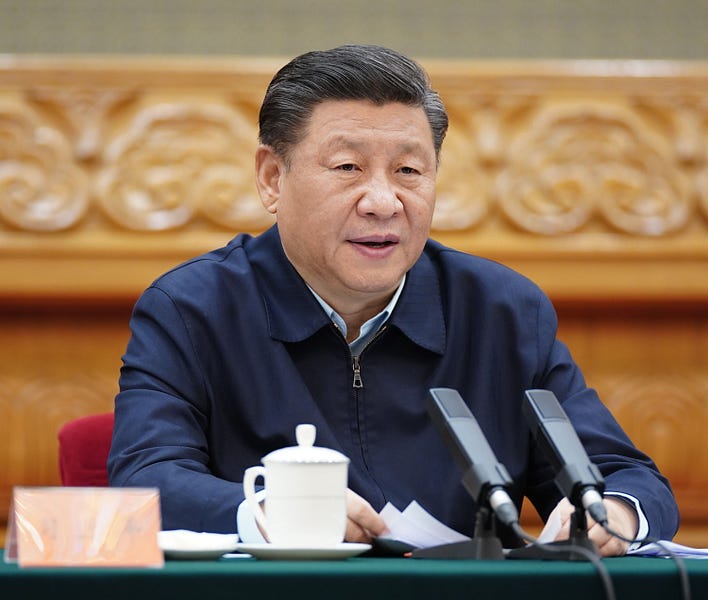

Photograph by Ju Peng/Xinhua via Getty Images.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.