Conservatives have a special duty to protect iconoclasts.

At first blush, this idea doesn’t quite square. Conservatism, properly understood, seeks to protect order and tradition. Why should it defend those who challenge the status quo?

There’s a simple answer: Because iconoclasts sometimes raise the right questions. Conservatives, at any given moment, could be preserving a bad idea, an unfair practice, or an outdated system. By making room for those willing to dissent, conservatives are actually guarding against decadence and a misguided sense of certainty. Ideas now considered invaluable were once thought heretical, after all: Isaac Newton’s and then Albert Einstein’s theories on gravity, Adam Smith’s understanding of markets, Frederick Douglass’ and Susan B. Anthony’s approaches to equality, Luis Alvarez’s research on the extinction of dinosaurs.

At the same time, however, we must never forget that iconoclasts are often dead wrong. Their ideas can be loopy, even dangerous. They’d have us believe in deranged conspiracy theories, in ancient aliens, that the position of planets and stars dictate human events. If some of these iconoclasts gained power, they could undermine generations of hard-earned wisdom and wreak havoc in essential institutions—the very things conservatives fight to prevent. America’s right must be confident enough in their own beliefs to listen to iconoclasts’ objections while staying principled enough to generally keep them away from positions of authority.

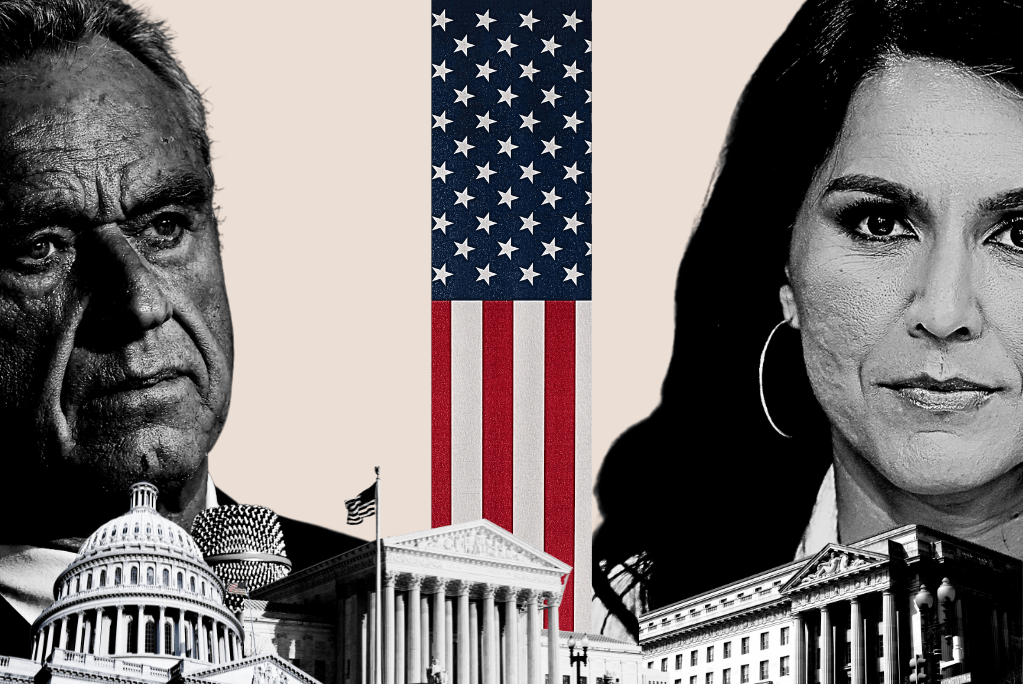

Perhaps Robert F. Kennedy Jr., President Donald Trump’s nominee to lead the Department of Health and Human Services, has some worthwhile thoughts about food production. Perhaps Tulsi Gabbard, Trump’s pick to serve as director of national intelligence, raises a decent point about the importance of civil liberties in an era of heightened surveillance. But, as with so many other iconoclasts, their occasional defensible ideas are wrapped up with a host of wrongheaded beliefs and troubling behaviors. Yes, hear them out. Sure, consider them intellectual provocateurs. But don’t let them within a country mile of federal executive power.

Many conservatives in the Trump era have adopted an anti-institutional posture that’s typically been reserved for progressives and radicals, and understandably so, as many of our most important institutions have failed in recent years to carry out their core missions. The pandemic, for example, revealed the poor judgment and politicization of too many public-health professionals. Too many elite universities have been hostile to viewpoint diversity and free speech. Too many journalists substituted their political preferences for dispassionate reporting. Some leading banks helped precipitate the Great Recession, and Congress seems incapable of seriously engaging with the most important issues plaguing the nation. Prosecutors in a number of our largest cities have grown indifferent to basic matters of law enforcement.

In such cases, the typical conservative approach of preservation and prudence—the approach perhaps best embodied by G.K. Chesterton’s fence allegory—would seem wholly inadequate. In those areas and plenty of others, we need major change—not more of the same. But the error some on the right are making in this moment is forgoing strong, stubborn, sober reform and instead finding common cause with people whose impulse is to swiftly and dramatically upend or tear down. Kennedy, Gabbard, and Elon Musk among others are conservative in neither political philosophy nor disposition. They seem to be animated primarily by their animus toward institutions.

But that’s not how conservatives choose allies; that’s typically how we choose opponents. Edmund Burke, arguably the founder of modern conservatism, is best known for his criticism of the French revolutionaries who wanted to overturn longstanding governing bodies and religious and social arrangements. More recent conservatives have seen themselves as fundamentally at odds with critical race and critical legal theorists and Marxists, all of whom argue that our key institutions are built on and perpetuate injustice and therefore need to be undone. Strong conservatives don’t team up with such institution-levelers in order to win a current scuffle; we oppose them because they threaten lasting societal damage.

Andy Smarick“Even if conservatives are frustrated with an important institution, we must recognize that those institutions should never be led by those whose primary qualifications are eccentricity and provocation.”

Daniel McCarthy“The dilemma of the last century has been resolved in favor of skepticism toward liberal scientific expertise that had marginalized the right for so long.”

This anti-institutional fervor on the right has fostered a strange type of argument in favor of Kennedy, Gabbard, and Kash Patel—as well as figures like Matt Gaetz, Pete Hegseth, Linda McMahon, and Mehmet Oz. “Sure, they might not be traditionally ‘qualified’ for these jobs,” the thinking goes, “but previous ‘qualified’ people in those roles were terrible. At least these people will shake things up.”

Of course we should be frustrated if someone purportedly qualified for a job fails at it. But if you have a bad experience with a doctor, you don’t seek a second opinion from someone unfamiliar with human anatomy just because he or she will “shake things up.” You find a better doctor. If your daughter’s teacher isn’t very good, you don’t “shake things up” and ask for a replacement who’s ignorant about phonics and child development. You find a better teacher. We should respect our institutions and the work of governing enough to recognize that disruptive novices are not the answer. There are plenty of tough-minded, highly experienced Republicans and conservatives—former governors, U.S. attorneys, state attorneys general, veterans of previous GOP administrations—who could responsibly implement meaningful reforms.

There’s one more reason for conservatives to avoid embracing figures like Kennedy and Gabbard, and it has less to do with their deficiencies than our understanding of and respect for key governing institutions.

Over the last generation, we seem to have lost the distinction between those who talk about politics for a living and those who actually take responsibility in positions of authority. Commentators and pundits think they are ready to govern, people in governing positions act like commentators and pundits, and the public ends up believing the two groups are interchangeable. That Kennedy, Gabbard, Hegseth, Oz, and so many other Trump nominees have been gadflies and television personalities is not a coincidence: This is the consequence of blurring the line between the two lines of work.

But experience in criticizing, speculating, and agitating is not sufficient preparation for devising and implementing the myriad reforms our institutions require. No, we need leaders deeply knowledgeable about policy content and process and who possess the hands-on experience and disposition needed to lead at the highest levels. Conservatives should be the first to protect the integrity of our governing institutions in this way and the last to allow those institutions to be turned into platforms for those pushing insensible ideas, whether related to vaccines or the traitorous Edward Snowden.

I want to be very clear here about what I am arguing—and what I’m not. Individuals have every right to take unusual, even wrongheaded, positions. But that does not mean that the most powerful seats in the American government should be held by those with poor judgment. We should appreciate that there is a fundamental difference between what a citizen can do and what a high-ranking public official should do.

Four years ago, as debates were raging over truth, disinformation, exaggeration, conspiracies, and the infamous seriously-not-literally divide, I defended (in a long essay for National Affairs) the use of a wide array of rhetorical devices, arguing that truth and meaning can be conveyed in a number of ways that may not pass the test of “literal accuracy.” My first point was that the public’s understanding of an issue can be aided by caricatures, fables, hyperbole, myths, parables, parodies, satire, and tall tales, even if each of these have some degree of untruth. But my second, larger point was that, while citizens and private groups might use these devices, public institutions and their leaders should not. We need the most authoritative institutions to be absolutely reliable, straightforward, judicious, and respectable. Americans must be able to trust such entities because so much rides on their statements and actions. Americans will only give these institutions the massive power they need to succeed if Americans believe those institutions are worthy of that power.

This is the same way we should understand the difference between the wild-eyed views of private citizens and prospective leaders. A citizen has every right to hold avant-garde positions far outside of the consensus of medical professionals. But we should not put such a person atop the nation’s largest public-health agency. A citizen has the right to be transgressive and express sympathy for some of our nation’s enemies. But we should not put such a person at the head of our intelligence community. A citizen has the right to bombastically include in a book a list of supposed agents of the deep state and imply criminal or civil action against opponents. But we should not put that person in charge of the FBI.

Even if conservatives are frustrated with an important institution, we must recognize that those institutions should never be led by those whose primary qualifications are eccentricity and provocation. You don’t strengthen an institution by elevating people who will bring chaos and subversion to the body; that is a recipe for the institution’s downfall. Conservatives must not lose the distinction between an external agitator and an internal leader.

There is always a role for inexperienced, intemperate iconoclasts in society. There’s even a small role for them in conservatism. We should be aware of their arguments and the evidence they marshal. But because they typically have too little respect for and too little familiarity with key institutions and because those institutions are so important to this nation, we should keep them out of the most important positions of public authority.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.