My favorite part of John McCormack’s stellar profile of Tucker Carlson has to do with what John calls “the Carlson cackle.”

If you’ve seen Tucker speak live at any point over the last five years or so, you’ve heard it. It’s distinctive—manic, mirthless, and prone to erupt when no one has said anything close to being laugh-out-loud funny, as John notes. He sounds like Frank Gorshin as the Riddler on the old Batman series dissolving into psychotic giggles after hatching his latest diabolical scheme.

There’s something aggressive and unnerving about it, as is usually the case with someone given to laughing a bit too hard at inappropriate moments. You find yourself wondering: Is it an affectation or is he bonkers?

“Carlson seems to want to convince his fans—and maybe himself—he’s having fun. It’s hard to believe he actually is,” John wrote, implying a certain logic to the cackle. But the alternative couldn’t be ruled out. “Is it possible Carlson has simply lost his marbles?” he went on to ask, never quite settling on an answer.

Affectation or bonkers? That question comes up a lot in politics now.

Another person wrestling with it is Mitt Romney, who’s on his way out of the Senate and into an uncertain future. If ever there were a man teed up for a happy retirement, it’s him; he has money to burn and a famously big, loving family to enjoy. But he doesn’t sound happy. “How am I going to protect 25 grandkids, two great-grandkids? I’ve got five sons, five daughters-in-law—it’s like, we’re a big group,” he complained with exasperation recently to The Atlantic.

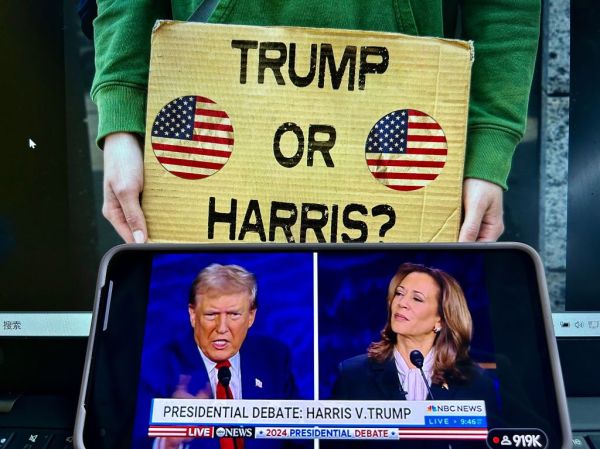

The person his kids and grandkids might need protecting from is the Republican nominee for president. Mitt is so worried about Donald Trump abusing executive power to harass the Romney family that it’s contributed to his decision not to endorse Kamala Harris, according to the Washington Post. When Trump talks about “retribution” against his political enemies, Romney takes him literally and seriously.

Should he? Is Trump’s “retribution” chatter an empty threat designed to motivate his fans to vote? Or is he bonkers enough to order a revenge campaign from the Oval Office?

“It doesn’t matter,” you might say, fairly enough. Whether Trump’s demagoguery is strategic or proof of insanity, he’s unfit for office either way. And American voters seem to agree that it doesn’t matter, as there seem to be enough of them who don’t care about either the question or the answer to reelect him. “Affectation or bonkers?” is a question for serious citizens, not ours.

One can’t help but wonder about it, though, the same way one can’t help but wonder about Tucker whenever he lapses into another Riddler-esque cackle. And that’s because, by his own admission, Trump has gotten “dark” in his rhetoric as Election Day approaches.

If he wasn’t already running the most demagogic presidential campaign in modern American history, he is now. And it will get worse.

‘Dark’ days.

“This is a dark speech,” he told his audience at a rally in Wisconsin last weekend. When a man who made “American carnage” the theme of his inauguration feels moved to remark on how grim his outlook has become, you know you’re in for something special.

He’s always played in the sewer as a politician (and as a human), but his poor showing at last month’s debate seems to have knocked loose what was left of his restraint. Maybe he’s attacking with every weapon available lately because he’s desperate to try to erase whatever advantage Kamala Harris gained at the event. Or maybe Tom Nichols is right that he’s entered an “emotional tailspin” after being outclassed on national television.

Either way (affectation or bonkers?), as David Graham has noted, we’ve entered a bad-even-for-Trump phase of demagoguery.

The smear campaign against Haitians in Springfield, Ohio, was the unofficial start of it. Somehow he managed to get through his first two runs for president without raising the specter of dark-skinned savages eating cats and dogs, but no longer. And although the Haitians have gotten the worst of it, his rhetoric about menacing foreigners has been unusually vivid of late in general. “They will walk into your kitchen, they’ll cut your throat,” he warned one audience before vowing to “liberate Wisconsin from this mass migrant invasion of murderers, rapists, hoodlums, drug dealers, thugs, and vicious gang members.”

The next day, in Pennsylvania, he imagined how America might end the scourge of violent crime (which is down this year). Trump has always fantasized about cops beating criminal suspects, as authoritarians are wont to do, but his latest iteration was oddly specific. “One rough hour—and I mean real rough—the word will get out and it will end immediately, you know? It will end immediately,” said a man who wants to choose the federal government’s chief law enforcement officer. Giving the police “one rough hour” to do whatever they like without fear of repercussions reminded many of The Purge.

His shots at Harris also have turned nastier and more personally insulting. She was born “mentally impaired,” he said at one event, adding that “only a mentally disabled person could have allowed this to happen to our country.” At another event he called her “a stupid person” while the crowd chanted “lock her up” for reasons that are unclear. (Murder, presumably.) Even some of his otherwise reliable cronies were uncomfortable with the digs at Harris’ intelligence.

Locking up his enemies is another evergreen Trump theme that’s gotten uncomfortably specific. A few weeks ago he threatened to prosecute lawyers, donors, political operatives, and election officials who are complicit in cheating on Kamala Harris’ behalf. Last Friday he extended the threats to Google, which he claims on the basis of God knows what is “illegally” suppressing positive stories about him and negative stories about Harris.

Those he’s been threatening are forced to gamble their families’ futures, a la Mitt Romney, on whether he means it or not. Are the threats an affectation designed to “work the refs” before Election Day and to be quietly dropped thereafter or is he bonkers enough to follow through if he wins?

We could spend the rest of this newsletter on the kaleidoscope of demagoguery in which he’s engaged lately. His recent commentary about Ukraine has been conspicuously Kremlin-esque, for instance, probably for no better reason than that he’s annoyed at Volodymyr Zelensky. His hysteria about cheating at the polls has also ramped up in preparation for “Stop the Steal 2.0” next month. And he apparently took to rooting for a government shutdown last week, per his usual habit of desiring maximum pain for Americans whenever he stands to benefit politically from their frustration.

On that last point, though, it’s more useful to consider how he responded to Hurricane Helene, which laid waste to parts of Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and the Carolinas this week.

Storm-chasing.

Announcing a visit to North Carolina on Monday to view the damage, Trump said, “I’ll be there shortly, but don’t like the reports that I’m getting about the Federal Government, and the Democrat Governor of the State, going out of their way to not help people in Republican areas.” Later he posted a photo of Harris on the phone with FEMA, alleged that it must have been staged because her headphones weren’t plugged in (they were), and accused her and Biden of having “left Americans to drown in North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, and elsewhere in the South.”

Democrats are deliberately leaving Republicans to die is strong stuff even by the standards of disaster politics. As the cherry on top, when Trump arrived in Georgia on Monday he casually accused Biden of not so much as returning Gov. Brian Kemp’s call for help.

None of that is true, as Kemp himself might tell you:

FEMA dispatched emergency management teams to the affected states even before the storm arrived. Biden pre-approved emergency declarations for Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina to get the funding rolling ASAP. The spending bill that passed Congress last week (and averted the shutdown Trump was craving) lacked FEMA money not because Democrats want to see red states wiped out, but because negotiators “were forced to acquiesce to the demands of Congress’ most conservative fiscal hawks, whose votes were thought to be pivotal for passage.”

On Monday Trump favorite Rep. Matt Gaetz took to Twitter to complain that his home state of Florida would be happy with half of what Congress has given to Ukraine—but Gaetz, it turns out, voted against the funding bill himself. And when Trump was confronted by reporters about his claim that Democratic leaders went out of their way not to aid Republican counties besieged by the storm, the best he could do to defend the allegation was to say, “Just take a look.”

What makes this demagoguery truly next-level is Trump’s own record as president in treating disaster relief as a form of political patronage. The New York Times took a stroll down memory lane on Tuesday, revisiting numerous examples of him “threatening to withhold money from governors of blue states whom he saw as enemies, and promising ‘A-plus’ treatment for his allies.” (For my friends, everything.) FEMA was also given short shrift during his term in office as money was redirected from disaster management to immigration enforcement.

If he was quick this week to accuse Biden and Harris of prioritizing political allies over adversaries for hurricane relief, it’s because that’s the way his own mind works, not because of anything they did. It is maddening that he would get away with demagoging his opponents for a disqualifying dereliction of duty of which they’re not guilty but he is. Biden was rightly incensed by it: “I don't care what he says about me. I care about what he communicates to people that are in need.”

And so we’re left to puzzle over the usual question. Is this all a strategic gambit in the home stretch of a tight campaign in which Trump is cynically throwing whatever smears he can think of at the wall and hoping that something sticks? Or has this become less a presidential campaign than a psychological experiment to see what happens to a fragile narcissist’s mind under the immense pressure of losing a national popularity contest and potentially his freedom next year?

Affectation or bonkers? I think an appropriate answer is “Whichever it is, it’s about to get worse if Trump loses.”

If his politics has grown so “dark” already that he would lie about Biden and Harris leaving Republicans to drown, there’s no telling where the accusations might go as he copes with a defeat. During the first “Stop the Steal” effort, he tended not to identify specific people as prime suspects in the plot against him; “Democrats” and the companies that built the voting machines used in swing states were typically (but not always) about as concrete as the targets of the finger-pointing got.

This time he’ll be more particular, I suspect, per his warnings to election officials and to Harris’ donors and lawyers. And there’s destined to be more of a racial component to Stop the Steal 2.0 as Trump inevitably contrives some theory about illegal immigrants supplying the fraudulent votes that carried Harris to victory. The most demagogic campaign in modern American history hasn’t approached the limits of what it’s capable of if and when it faces the consequences of losing, particularly with J.D. Vance in Trump’s ear egging him on this time.

But what if Trump … wins?

The great disillusionment.

Our friend David French sounded bleak on Monday as he watched the hero of the American right gaslight millions about whether the president had taken Brian Kemp’s phone call. “As a country we don't quite know how to handle an entire party that trusts the most dishonest politician in modern American history more than they trust anyone else in politics,” David despaired.

Most of us “handle” it, I think, by pretending that it’s not a problem. Trump lost in 2020; he stands an even chance of losing in 2024; so long as the party that trusts him continues to lose, all’s well that ends well.

But that’s silly. It’s a form of cope, transparently. The kind of man running the kind of campaign Trump is running would be deplored by a decent people; as it is, the party that treats Trump as the most trustworthy figure in politics has gained enough support to plausibly win this election.

Watching the most demagogic campaign in modern American history actually prevail will forever poison how half of the population thinks of their country. And the uglier Trump’s message gets over the next 35 days, the more profound their disillusionment will be.

The losing side is always disgruntled after an election by having to live for four years under policies they disdain. But as Trump gets “darker,” the moral revulsion at seeing him rewarded with victory for his darkness will get stronger. It cannot be that someone who deliberately causes political opponents and election officials to fear that he’ll persecute them if he’s elected will actually be elected. There must be enough Americans who believe that crime doesn’t pay to deny power to a convicted felon and unapologetic coup-plotter.

What if there isn’t? How does one live contentedly in the minority among people who want to be governed by a character like Trump, and not only want to be governed by him but want it so badly that they’ll believe anything he tells them? We can blame the abundant supply of gutter populism in right-wing media only so much; ultimately, this is a demand problem.

A nation in which half the electorate has stopped caring whether the demagogue it could elect is clinically bonkers or just extremely ruthless in his political affectations isn’t a nation whose long-term stability we should count on.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.