I rise to defend Kevin McCarthy from Liz Cheney. And from my boss.

If reading that felt awkward, imagine how it felt to write it.

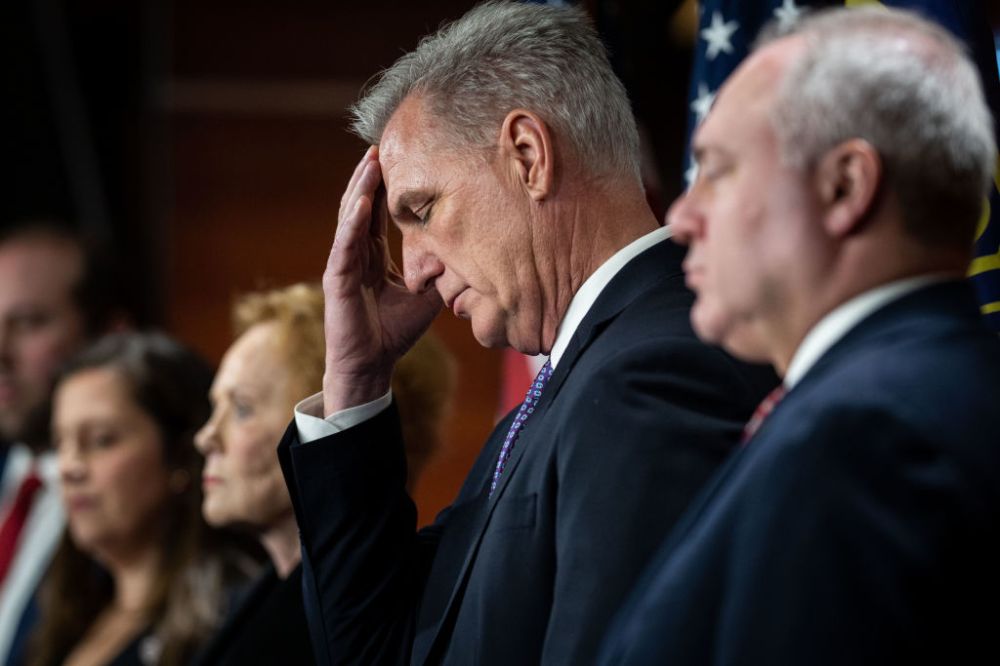

When two honorable conservatives point the finger at one of America’s least honorable politicians, the rooting interests are clear. In a party teeming with amoral opportunists, McCarthy is the supreme specimen. He dreamed for years of being speaker of the House, and as the right’s populist revolution turned the GOP into a party by and for demagogues, he undertook to make whatever moral compromises were necessary to protect his ambition.

Many others have done the same, but few did so with such gusto to have earned a nickname from Donald Trump reflecting Trump’s sense of personal ownership.

Never once has McCarthy betrayed a hint of ambivalence about it. He’s the very model of an unprincipled careerist sellout. If Liz Cheney is matter, “My Kevin” is antimatter.

So her contempt for him is natural, and would have been natural even if McCarthy hadn’t led the coup within the House Republican conference that ousted Cheney from her place in leadership. On Sunday she appeared on Face the Nation to comment on the ongoing fiasco within the House GOP majority and to lay blame for it at McCarthy’s feet.

“This is correct,” The Dispatch’s own Steve Hayes tweeted about Cheney’s comments.

Is it?

It feels correct. The indictment of McCarthy’s character is indisputable. It is in fact disgraceful how the former speaker accommodated himself to Trump, toadied to him as necessary to protect his standing in the conference, and made strategic alliances with some of the least savory populists in politics. If anything, Cheney went easy on him: If not for Kevin McCarthy’s amoral passivity, Marjorie Taylor Greene might never have made it to Congress to begin with.

After the 2020 election, McCarthy signed on to the preposterous Texas lawsuit to invalidate electoral votes in swing states Joe Biden had won. On the evening of January 6, 2021, following his brush with death hours earlier, he joined most House Republicans in voting against certifying Biden’s victory. Months later, he opposed the creation of a bipartisan January 6 commission, then attempted to sabotage the House’s new January 6 committee by appointing insurrectionists like Jim Jordan to it. “My Kevin” very much did “embrace the most radical and extreme members of our party,” in Cheney’s words, by helping to facilitate Trump’s coup attempt and to shield him from the consequences afterward.

He’s an appalling person. If Trump embodies the rotten id of the populist base, McCarthy embodies the rotten id of the Republican establishment.

But why does Cheney, or Steve, think anything would have been different this month if the now-former speaker had behaved differently at some point in the last three years?

How do we get from “Kevin McCarthy is a disgrace” to “this speaker mess is ultimately Kevin McCarthy’s fault”?

What irks me about Cheney’s critique is that it exculpates Republican voters for the incentive structure they’ve created for their leaders.

That’s not intentional, I realize. If anyone knows from painful experience how twisted the politics of the grassroots right have become, it’s Liz Cheney.

But the idea that House Republicans might have behaved better these past few weeks if not for McCarthy implies that there’s something he might plausibly have done as leader of the conference since 2020 to steer them in a more productive direction. What, specifically?

“He shouldn’t have agreed in January to let any single member of the House bring a motion to vacate the speakership,” Cheney might say. Okay, but then he probably wouldn’t have gotten the votes he needed for speaker. And even if he had held out for a higher threshold for a motion to vacate, it’s not clear that would have saved him earlier this month. Remember, McCarthy originally proposed that five members should be required to file a motion, not one. When he was ousted as speaker a few weeks ago eight Republicans voted against him, more than enough.

He had two options in January when the MAGA bloc of the conference dug in and demanded power to vacate the chair as a condition of handing him the gavel. He could have ignored them and sought to replace their votes with Democratic support, making whatever concessions Hakeem Jeffries demanded of him. Or he could have stared down the MAGAs and hoped that the grassroots right would pressure them into capitulating.

Neither option was realistic. A deal with the Democrats would have infuriated Republican voters, destroying McCarthy’s credibility before his speakership had begun. And there was no grassroots ire toward those like Matt Gaetz who blocked McCarthy initially, needless to say. On the contrary, populists loved the idea of the MAGA bloc holding out for leverage to yank the gavel away from McCarthy down the road if and when he didn’t “fight” hard enough.

Republican voters created a terrible incentive structure, and McCarthy was forced to navigate it to become speaker. Simple as that.

“In that case, he shouldn’t have run for speaker,” Cheney might respond. “He should have had the personal integrity as a leader not to make concessions which he knew would lead the conference into dysfunction.”

Sure, that’s what an honorable person would do. But if McCarthy had stood aside on principle, a less principled Republican would have leaped into the void he created and made the concessions he’d refused to make in the name of winning the gavel themselves.

Cheney has painful experience with that too. She was replaced as chair of the House Republican conference by Elise Stefanik, another careerist in the McCarthy mold willing to trade every fiber of her honor to get ahead professionally. Stefanik would have caved on the motion to vacate for the sake of being elected speaker. Or Steve Scalise would have. Or, if not, the MAGA bloc would have held out until a candidate came forward willing to give them what they wanted.

That’s how the Republican hostage crisis works. The populists have no incentive to yield because Republican voters refuse to punish them for not being “team players.”

It would not surprise me, in fact, if Kevin McCarthy had managed to convince himself in January that he had done a good thing, even a responsible thing, by caving to the MAGA bloc on the threshold for a motion to vacate.

And if he did, I’m not sure he’s wrong about that.

For years I’ve imagined most Republicans in Washington as being afflicted with what I call “Marco Rubio Syndrome,” named in honor of the candidate in 2016 who saw most clearly what Trump’s ascent portended for the party and who ended up accommodating him anyway. Marco Rubio Syndrome is when a conscientious politician talks themselves into believing that they’re behaving morally—not just expediently, but morally—by cooperating with the worst influences in right-wing politics. The logic is this: If I don’t go along, I’ll be replaced by someone who’s truly terrible.

It’s a transparently self-serving rationalization for collaborating with illiberalism among those who know better. Nine times out of 10, it leads the afflicted person to vote the same way as the hypothetical populist gargoyle whom he fears would replace him in office, erasing the alleged moral distinction between the two.

But on the 10th time out of 10, there really is a difference. Which makes condemning Marco Rubio Syndrome … tricky.

It’s conceivable that had Rubio not run for reelection to the Senate in Florida last year we would have ended up with Sen. Matt Gaetz. And for all his faults, for all his spinelessness in avoiding conflict with Trump, Rubio is better than Gaetz. He continues to support funding Ukraine, for instance, and he declined to join the populist effort on January 6, 2021 to prevent Congress from certifying Biden’s victory. As much as we might mock him for justifying his uneasy alliance with populists as the least bad option under the circumstances, he’s not quite entirely wrong.

The same goes for Kevin McCarthy. It’s trivially easy to imagine him telling himself at various points on his road to the speakership that if he didn’t go along with Trump and the populists, he’d be replaced as leader by someone who’s truly terrible. And he’s probably right.

Go back to 2020. What would McCarthy and the Republican conference have gained if he had behaved more like Liz Cheney?

If he had joined her in impeaching Trump after January 6, his career would have been over as surely as hers is. Maybe even more surely: As the highest-ranking Republican in the House, he would have been a target of special opprobrium from Trump fanatics. Primarying him, not her, would have been their premier revenge operation in 2022. And when it succeeded, other House Republicans would have learned the lesson that not even their most powerful colleagues, with the deepest war chests, were safe once they’d earned MAGA’s wrath.

Let’s try a different scenario. Imagine that McCarthy had remained on Trump’s good side throughout the coup-plot trauma of 2020-21 but then began to assert himself as an independent leader of the conference in 2022. On Face the Nation, Cheney complained about McCarthy elevating certain outré House Republicans, “some of whom are white supremacists, some of whom are antisemitic, a number of whom were involved directly in the attempt to seize power and overturn the election.” Pretend that he hadn’t done that—no plum committee assignments for the likes of Greene and Thomas Massie, no committee gavels for figures like Jim Jordan.

How long do we think he would have lasted as speaker in that scenario, making enemies of populist foot soldiers under the protection of the MAGA capo di tutti capi? Would he have become speaker at all?

The reason he made nice with figures like Greene, Massie, and Jordan in the first place was because he knew they’d be agitating to have him removed and replaced with a kindred populist spirit if he hadn’t. Without them, it’s hard to see how he would have gotten to 218 votes in the first place. It’s notable, in fact, that none of the three joined Gaetz’s rebellion against McCarthy earlier this month. To some degree, the speaker’s willingness to accommodate them domesticated them and led them to work within normal political channels. (Or what passes for normal in 2023.)

If McCarthy had vowed to sideline the populists in his conference from the start and been blocked from the speakership, one of two bad outcomes would have followed. Either a fellow “normie” Republican like Scalise would have stepped forward and been more agreeable to the MAGA bloc’s demands or a member of the MAGA bloc itself like Jordan would have stepped forward and run for the gavel. And in this case, absent the hard feelings he engendered in some of his colleagues with his behavior recently, Jordan might have fared better than he fared last week.

Kevin McCarthy can point to all of that and say, as any victim of Marco Rubio Syndrome might, “Aren’t you glad I made the moral compromises I did?”

We avoided a debt-ceiling crisis. We dodged a shutdown (temporarily). The tap for Ukraine hasn’t been turned off yet. Isn’t it better that we had Speaker McCarthy than Speaker Jordan?

He didn’t do badly for a guy presiding over an unmanageable coalition of two mutually hostile parties, whose majority was much smaller than expected thanks to the truly culpable figure in this mess.

For all his sleazy maneuvering, McCarthy remains as of this writing the only person capable of gaining 218 Republican votes in the speaker’s race. (The only mortal, I should say.) In a party whose establishment has been remade in Trump’s image of chaos and selfishness, he managed something resembling functional government.

For nine months.

The best I can do to vindicate the Cheney-Hayes thesis that the House might look different today if Kevin McCarthy had made better choices is to revisit January 6 again.

If he had thrown his weight as minority leader behind impeaching Trump, perhaps more than 10 House Republicans would have rallied behind the cause. What if 30, led by McCarthy, had voted to impeach instead? Or 50? There’s safety in numbers. McCarthy would have been primaried into oblivion for his “treason,” but many of the rest might have survived, as there could have been too many of them to punish. And if they got away with defying Trump in a matter as momentous as that, the MAGA bloc in the House might have been more cautious in the future about antagonizing their colleagues.

I can’t disprove that thesis. But I don’t buy it.

Liz Cheney was the third-ranking House Republican when she voted to impeach Trump and the bearer of one of the most famous names in right-wing politics. Even so, her vote ended up giving practically no political cover to her Republican colleagues. It’s hard for me to imagine why Kevin McCarthy, a politician with no constituency outside the donor class, would have changed that equation meaningfully by joining her. If anything, the modicum of goodwill among populists he had earned over the years by kowtowing to Trump would have melted away. He would have reverted instantly in their eyes to a “swamp monster” and Paul Ryan crony, just another holdover from the corrupt pre-Trump GOP who needed to be purged to purify the party.

Right-wing media would have savaged him just as they savaged Cheney. He wouldn’t have stood a chance. Any House Republicans toying with following his lead by supporting impeachment would have watched and thought “there, but for the grace of Trump, go I.”

In fact, if you want to understand how little room to maneuver Kevin McCarthy had in leading this conference, consider the figure of Tom Emmer.

Emmer is the House majority whip and the tentative frontrunner in the new Republican speakership election to be held Monday night. But he has a problem: He voted to certify Biden’s victory on January 6, 2021, one of just two speaker candidates among the nine running to have done so. He hasn’t endorsed Trump for president yet either (although neither had McCarthy), and as head of the National Republican Congressional Committee last year he favored mainstream Republican candidates over populist ones.

All of which is commendable as a matter of basic civic responsibility and therefore potentially disqualifying in a modern Republican leader.

So Emmer is looking to atone, even before he’s taken the gavel.

If you thought the concessions McCarthy had to make to the MAGA bloc were bad, God only knows what pledges of fealty Emmer will be led to engage in privately for the sake of gratifying his own ambition.

The problem with blaming McCarthy for Republican dysfunction is ultimately a matter of recognizing that there’s only one figure in the party with a meaningful following. The culture of the modern right flows from him, at the leadership level and down below, and sometimes in symbiosis:

After that was reported on Friday, Semafor’s Benjy Sarlin sniffed, “It turns out when you train a certain base to think that one person is entitled to an elected job whether or not they have the votes, and then you keep insisting it even after the votes aren’t there, and keep demanding more and more votes, they have a playbook on how to react.” They do. And it wasn’t Kevin McCarthy who wrote that playbook.

But he sure was willing to implement it, even occasionally at the risk of his own personal safety. We can and should despise “My Kevin” for that, as Liz Cheney plainly and rightly does. I won’t miss him.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.