From time to time in this newsletter, we take up the question of “cynic or convert?”

Nearly every conservative of significance within the Republican Party has reconciled themselves to Trumpism since 2016, but the earnestness with which they’ve done so varies. Many are careerists who privately despise Donald Trump and what he stands for but despise the idea of losing their political stature just a little more. They’ve pledged their fealty because they had to, not because they wanted to. They’re cynics.

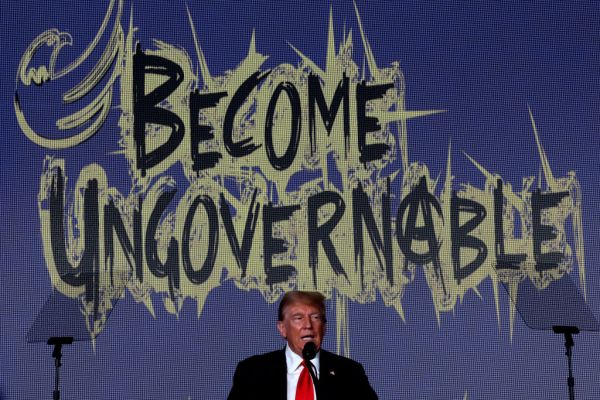

Other conservatives started out despising Trump but have grown to idolize the man and his movement. A few might have been won over to populist-nationalism on the ideological merits (giggle) but for most, I think, the appeal is more primal. MAGA politics is a daily bath of authoritarian fervor, cultural outrage, and insatiable suspicion that malicious conspiracies are afoot in every part of society. Whatever may have motivated these conservatives to join the cult, they’re enthusiastic converts now.

Usually, it’s pretty easy to tell one type from the other.

Nikki Haley is an obvious cynic. Her years-long half-hearted vacillation about whether Trump is fit for office is clearly a ploy to try to preserve her viability in the GOP in case the party comes to its senses someday. Contrast her with Mike Lee, who holds a safe Senate seat and is unlikely to occupy any higher office (hopefully!), yet chatters manically about Trumpist priorities on social media day in and day out. He’s a convert, a true fanatic.

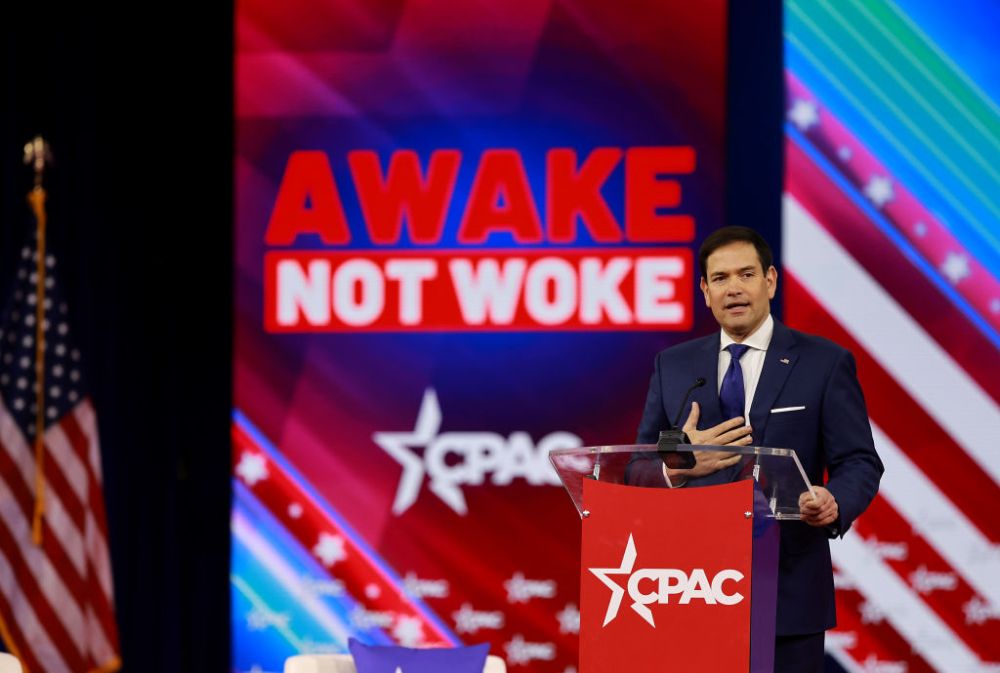

Which one is Marco Rubio?

Not long ago, I would have called the senator from Florida a textbook example of a cynic. No one spoke more presciently in 2016 about the long-term civic damage that would be done to right-wing politics and to America if Republicans embraced Trumpism. And no one described Trump’s personal unfitness for the presidency in terms as stark. At times on the trail that year, Rubio was visibly shaken by how easily Reagan conservatism had been co-opted by a lowbrow demagogue.

When he made peace with Trump after the primary, it was a straightforward matter of an ambitious young Republican who knew better choosing to protect his perch in the GOP. Pure cynicism, same as Haley.

Is it still so straightforward today?

Marco Rubio is a curious case from the “cynic or convert?” perspective because even at this late date, I think, one can plausibly argue the question either way. There are reasons to believe he’s become a glassy-eyed MAGA zealot. And there are reasons to believe he remains an opportunist red in tooth and claw, possibly even a quietly idealistic one.

But either way, no one on the American right embodies the corruption of conservatism quite like Marco Rubio does. So much so that his ending up as Trump’s running mate this year feels like the only fitting conclusion to the GOP’s descent into civic degeneracy since 2016.

A bit of trivia about Marco Rubio that sticks in my mind is that he never thanked the Tea Party in his Senate victory speech in 2010.

Oversights happen, but that was an odd one. Earlier that year, Rubio had been touted by the New York Times as “The First Senator from the Tea Party.” His longshot Senate primary challenge to centrist favorite Charlie Crist was celebrated by grassroots conservatives throughout the campaign as a populist insurrection against the stale Republican establishment. Rubio had every reason to spike the ball on their behalf on election night. He did not.

I don’t think it was an oversight. I think for most of his career he was uncomfortable with populism and keen to keep it at arm’s length. The distress he evinced in 2016 about the, shall we say, animal spirits Trump had unleashed on the right was sincere. Marco Rubio didn’t want to burn down “the system.”

Remember, as a young politician in Florida, he was an ally (if not quite a mentee) of Jeb Bush. After he joined the Senate, his biggest legislative initiative was a bipartisan immigration reform bill. Until recently, he reliably supported foreign interventions favored by the so-called foreign-policy “blob” in D.C.

When he ran for president in 2016, he was the clear favorite of the same establishment class that had championed Crist in his 2010 Senate race. More so than even Haley, who ended up endorsing him, Rubio symbolized center-right conservatism’s potential to gain converts among blocs like young adults and nonwhites who traditionally favored the left. He was the future of the GOP—the “Republican savior,” as Time magazine had dubbed him in 2013.

Then he got smoked by Trump in the primary. And, no doubt to Rubio’s private horror, Trump did not get smoked by Hillary Clinton in the general election. The shelf life of gonzo right-wing populism would be extended by four years, at least.

The senator, then just 45 years old, decided to play along with the new leader of his party rather than burn any bridges (or retire), but his discomfort with Trump’s politics still flared occasionally. In 2018 he published an op-ed in defense of nationalism that resorted to blatantly misdefining the concept so that Rubio could find something praiseworthy to say about it. “A true American nationalism isn’t about a national identity based on race, religion or ethnicity,” he wrote. “Instead, it is based on our identity as a nation committed to the idea that all people are created equal, with a God-given right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

The “true” nationalism he described there sounds suspiciously like classical liberalism, which Marco Rubio has always preferred. It sure doesn’t sound like Trumpist nationalism, the point of which is to identify and subjugate various tribal “enemies within.” A movement bent on distinguishing “real Americans” from others is, by definition, not gung ho on the idea of a shared national identity.

But this is the sort of thing Rubio had to tell himself to make his pacification during Trump’s presidency tolerable. He was biding his time until 2020, when MAGA would at last lose at the polls and Republicans would begin to tilt back toward conservatism.

Trump did lose, and Rubio remained enough of a principled conservative after the election to resist the Republican effort to block Congress from certifying Joe Biden’s electoral votes. But then a funny thing happened: Republicans … didn’t tilt back toward conservatism. They tilted further toward Trump.

And that’s when Marco Rubio began to change.

The 2020 election and its aftermath taught the senator two lessons, I think. One was that Trumpy politics wasn’t a passing fad. The shelf life of indefensible populism had been extended again, this time indefinitely as right-wing voters evinced no interest in reverting to Reagan-style politics. Rubio could make peace with that or not, but there was no longer any point to “biding his time” and waiting for Republicans to change.

The other lesson was the shifting nature of Trump’s electoral coalition. Although he fell short against Biden, he made significant gains with Hispanics—and Rubio took a keen interest in it. A week after Election Day, he crowed with excitement to reporters that “the future of the party is based on a multiethnic, multiracial working-class coalition.” He’s continued to use that phrase in the years since, and no wonder: If Hispanic voters are warming up to a more populist GOP, the GOP’s most prominent Hispanic politician will surely grow in stature and influence within his party.

It’s no coincidence that, as Trump’s polling with Hispanics has improved further in 2024, Rubio has become a top-tier candidate for the vice presidency.

In short, Trump has actually done what Rubio hypothetically would have as the Republican nominee in 2016: make inroads with an important constituency that traditional conservatives like Mitt Romney and John McCain struggled with. Imagine Rubio digesting that fact in early 2021 while also confronting the hard reality that populism in the GOP is here to stay. Under that sort of psychological stress, it’s easy to see how he might have begun to appreciate certain political virtues of Trumpism and how his cynicism might have started to give way to an earnest conversion.

Emphasis on “might.” If Rubio is a convert to populist policy, it’s thus far a partial conversion.

For instance, when he took the unusual step as a Republican of siding with workers in a union drive at an Amazon facility in early 2021, he specified that he was doing so only because Amazon had “decided to wage culture war against working-class values.” That’s an idiotic position on the merits—unionization isn’t about forcing management to be less “woke”—but it was, it seems, the best a natural conservative like him could do to talk himself into solidarity with labor.

As another example, Rubio remains enough of a hawk to have partnered with Democrats last year on a bill clarifying that the president has no power to withdraw the United States from its treaty with NATO without approval from the Senate. The target of that legislation is obvious, and it ain’t Joe Biden. But Rubio is also now enough of a skeptic of the Western coalition to have voted twice this year against further aid to Ukraine, justifying his refusal to do so on “America First” grounds that securing the southern border should be a higher priority.

Try to imagine pre-Trump Marco Rubio, the Republican face of the so-called Gang of Eight in 2013, abandoning an American ally to Russian conquest because illegal immigration needs to be solved first. And then voting against the bipartisan immigration enforcement bill negotiated by GOP Sen. James Lankford of Oklahoma back in February.

Cynic or convert? Are these examples of Rubio saying what he knows he needs to say to boost his VP stock? Or has the pressure to conform to Trumpy populism finally gotten to him?

He’s a sellout either way, of course. But to fully appreciate just what a sellout he’s become, consider how deep into the tank he’s gone lately to defend Trump’s most destructive illiberal impulses.

Weeks ago, he was asked on Meet the Press whether he’d accept the results of the presidential election. For the Marco Rubio of 2016, righteously anxious about Trumpism’s corrosion of “norms,” that would have been an easy question. For the Rubio of 2024, a populist fanatic in earnest or a pretender angling for a spot on the national ticket, it’s a stumper:

Last week, after Trump was convicted in Manhattan, Rubio seized the opportunity to display his new populist bona fides in full flower. Partly that meant stooping to the sort of undignified pugilistic hyperbole that’s common on partisan social media …

… but much worse was how hard the senator strained to equate the verdict against Trump with the sort of “show trial” that one sees in communist countries.

In an op-ed for Newsweek, Rubio described Trump as a “hostage,” implied that a jury in a liberal jurisdiction like Manhattan couldn’t possibly have been fair, and uncorked a long culture-war rant that ended with gripes about “our ruling class of oligarchs and alleged experts.” Read his piece and you’ll find it indistinguishable from something you might see at American Greatness; a vote for any candidate other than Trump, Rubio concluded, is a vote to “criminalize the traditional American way of life.”

There’s a lot we might say (and have said) about Trump’s trial in New York, but one thing it wasn’t was a “show trial.” Rubio, whose parents fled Castro’s Cuba, knows what a “show trial” is; he knows that the defendant in one doesn’t receive due process or appeals; and he knows what sentence is usually imposed after the inevitable guilty verdict. That he would argue otherwise means that his cynicism has reached the point where he’s now willing to tell any lie on Trump’s behalf or his conversion has metastasized to the point where he truly can no longer see the difference between a trial in America and a “show trial.”

Rubio is a picture-perfect caricature of what he feared eight years ago that Republicans would become under Trump’s influence. “Popularity is not leadership. It never has been,” Rubio told an audience in 2006. “Leaders tell people what they need to hear, not what they want to hear.” Almost 20 years later, his ethos has become the precise opposite, rendering him a sort of ventriloquist’s dummy—“Little Marco,” we might call him—for the most repulsive political figure in modern American history.

In a party overflowing with weak, disgraceful conservative sellouts to authoritarianism, he might be the very weakest.

But as I said, Rubio would be the perfect running mate. And not just because he might help win over Hispanics.

Trump’s takeover of the old GOP is like a barbarian horde invading a kingdom and conquering it. In that circumstance, it wouldn’t be unusual for the defeated monarchy to marry off one of its princesses to the barbarian king in order to cement the union of their tribes going forward.

Princess Marco will be an ideal bride for King Donald, joining the conservative future in formal partnership to the populist present. Putting Rubio, the great establishment hope of 2016, on the ticket could convince many reluctant Reaganites who supported Nikki Haley in this year’s primaries that it’s worth rolling the dice on Trump one more time in November, if only to give Princess Marco a chance of becoming President Marco.

The conservative dream of 2016 might be realized after all! It’ll just have taken a, shall we say, circuitous route to becoming reality.

If you’re very favorably disposed to Marco Rubio and desperate to believe that he’s still the idealist of 2016 deep down, you can even concoct a scenario in which he’s been secretly working on behalf of Reaganism all along. If he ends up as VP and Trump dies in office, partisan pressure on the right to support the new president will give Rubio political cover to implement some traditionally conservative policies if he’s so inclined. Under his leadership, the right might become more classically liberal by 2028 than it is in 2024. If so, if this is all a sort of “long con” to put Rubio in a position where he might restore sanity, his efforts to ingratiate himself to Trump might be justified retroactively.

But I wouldn’t bet that Senator Show Trial is bluffing.

And if Trump doesn’t die in office and Rubio is counting on parlaying the vice presidency into winning his party’s nomination in 2028, I have news for him: It’s not going to happen. I think.

If Marco Rubio went all-in on Marjorie Taylor Greene-style populism as Trump’s No. 2 and Trump endorsed him in 2028, he’d admittedly have a solid shot at the nomination. But there’s a lot of pre-Trump Republican stink on him that would need to be scrubbed off and I’m not sure that anything could do it. He speaks “demagogue” as a second language and true populists can tell, as surely as one can tell by a person’s accent if they’re a native or from somewhere else.

Marco Rubio is an immigrant in MAGA-land and the locals don’t like immigrants.

He can prattle on forever about “a multiethnic, multiracial, working-class coalition” but to be the people’s choice in this lousy party he’ll need to become considerably more Trumpy than he already is. More argle-bargle about “real Americans”; more hysterical attacks on institutions like the justice system; more betrayals of U.S. allies under fire like Ukraine. To fulfill his presidential dreams he will, quite simply, need to become one of the most loathsome figures in a movement that’s already top-heavy with them. I’m confident he has it in him. He’s well on his way.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.