“The future of the party is based on a multiethnic, multiracial working-class coalition.”

That’s what an excited Marco Rubio said after the 2020 election, when Republicans beat expectations with Hispanic voters and swept tossup races in the House. A meaningful share of blue-collar voters who typically lean left had gotten spooked by progressives wanting to defund the police and voted conservative that fall. Rubio sensed an opportunity in the aftermath. A post-Trump GOP that pivoted to a more working-class agenda, culturally and economically, might cannibalize Democratic support among nonwhites and build an electoral juggernaut.

Fast forward to this week, when the new Republican-controlled House was sworn in and promptly sought to defund an IRS expansion that makes it easier to audit the upper class.

Soon those same Republicans will bring to the House floor Rep. Buddy Carter’s Fair Tax Act, which would replace income taxes with a federal consumption tax. The potential effects of that are complicated, as tax reform always is, but one analysis of shifting to a consumption tax projects that “taxes would rise for households in the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution, while households in the top 1 percent would receive an average tax cut of over $75,000.”

These are curious priorities for a party aiming to build a multiethnic, multiracial working-class coalition.

But for a party that’s spent years struggling to fill an ideological void, they’re understandable. It’s natural when faced with uncertainty to seek solace in what’s familiar.

Last weekend Ross Douthat published a column in the New York Times heralding the return of the pre-Trump GOP to power in Congress. Some liberals countered that the new House majority isn’t the same as the pre-Trump majority but rather “the tea-party movement re-baptized in Trump’s waters of rage.” Some Never Trumpers sneered that Douthat was delusional to believe that a party beholden to populists, pre- or post-Trump, could ever govern responsibly.

I didn’t read him as being naive about the nature of the new majority or its ability to govern, though. His point, I thought, was one with which liberals and Never Trumpers typically agree—that while the personnel and motives have changed a bit since Trump took over the party, House Republicans were and are a dysfunctional, unserious bunch with no vision beyond “mostly performative gestures and fiscal apocalypticism,” in his words.

There’ll be much more rhetoric over the next two years about shrinking government than there was during the Trump presidency, a “return of the pre-Trump GOP” superficially. But in substance the party will continue to practice the usual politics of confrontation in order to paper over its lack of consensus on policy. Right-wing factions can’t agree on what they want apart from agreeing that they don’t want what the left wants; until a broadly agreeable policy agenda takes shape, House Republicans will coalesce around not letting the left get what it wants.

The last time the GOP had something resembling a unified policy vision was 2012, I think, not 2016. Trump had strong policy preferences on discrete topics, like sealing the border, but he was malleable enough on basic fiscal matters to have signed an old-school Ryan/McConnell tax cut into law in his first year. Ed Kilgore reminds us that, for all of his talk about fighting for the little guy, Trump was prepared to take a wrecking ball to Medicaid in pursuit of repealing Obamacare. And some of his most deeply held populist convictions, like slapping tariffs on imports and ending American interventions abroad, continue to face sizable opposition within the Republican Party.

Trump influenced and informed the right’s identity crisis but he didn’t resolve it. We continue to wait for a new Ronald Reagan to help clarify the direction of the right ideologically and to galvanize Republican voters behind it. In fact, I suspect part of the reason such an intense cult of personality formed around Trump is because there was no consensus suite of policies for conservatives to unite behind. The eternal imperative to confront the left requires a rallying point; if there are no broadly shared ideas to rally to, the tribe will rally to the leader instead.

If I’m right that 2012 rather than 2016 was the last time Republicans had something resembling a shared vision of government, it helps explain why losing that year’s election was so traumatic and deranging for them. If the right can’t win by preaching small-government conservatism, how can it win? What should it preach instead?

Ten years later, we’ve yet to settle the debate sparked by those questions. Until we do, the answer is simply to say and do whatever’s necessary, up to and including staging a coup attempt on false pretenses, to win. Gain power and worry about what to do with it later.

Which brings us to why the pre-Trump GOP, the one that made a pretense of caring about the size of government, is back in vogue. Sort of.

Some reasons are obvious. As Trump’s political star dims (a bit), there’s suddenly political space for small-government traditional conservatives to reassert their priorities. Chip Roy is an example. You may disdain his policies or his political style but by all accounts he means what he says. Congress is overflowing with careerists who’ll believe whatever’s required in order to move up the ladder—ahem—but there are still a few true believers around. They’re seizing the opportunity created by Trump’s waning influence to advance their ideology.

The dynamics of divided government whenever a Democrat is president also tend to empower fiscal conservatives. Nothing brings out the inner libertarian in right-wingers like spending two years watching tax-and-spend liberals lavish taxpayer money on their social priorities. Whether you’re a devout deficit hawk like Roy or a cultural populist who simply likes to drink liberal tears, you can get behind an agenda that aims to roadblock new Democratic spending.

And that’s the key point. Tea Party obstructionism is a place where conservative ideologues and lib-owning MAGA types can meet and lock arms, a familiar placeholder ideology while the intellectual muddle on the right drags on. The different factions might not agree on entitlements or Ukraine funding or Big Tech, but they can certainly agree on pugnacious brinkmanship designed to thwart Democratic fiscal policy.

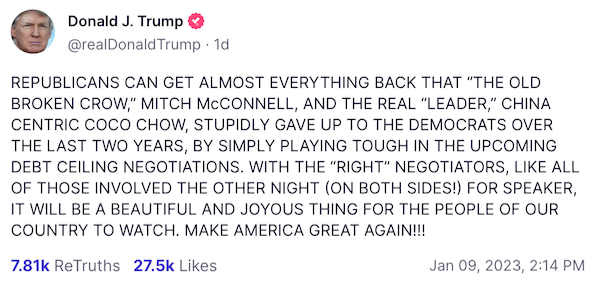

Which is how we get this guy, who increased the national debt by trillions of dollars as president, suddenly demanding a standoff over raising the debt ceiling.

Reading that, one wonders whether Trump himself has grown insecure about the ideological direction of the right and feels obliged to hedge his bets by being uncompromising on a fiscal conservative priority. Probably not. More likely is that he, of all people, grasps what the politics of confrontation requires of Republican leaders. You can be an old-school small-government conservative or you can be a big-government nationalist but you must be confrontational with the left. The coming debt-ceiling standoff will be the highest-stakes confrontation between the parties in years. Republicans must “play tough,” period.

What they should aim to obtain in policy concessions by playing tough is beside the point, enough so that Trump didn’t feel compelled to spell it out. The fight is the point. In 2011, at the height of the right’s Tea Party fervor, it was possible to believe that debt-ceiling brinkmanship was a good-faith attempt to bring government down to a sustainable size. Twelve years later, following a period in which Republicans enjoyed total control of government yet did nothing to shrink spending (less than nothing, really), it’s impossible to see the hostage-taking as more than confrontational posturing for its own sake.

“Us against them” is a helpful storyline when you can’t agree on who “us” is but can all agree on who “them” is.

There’s another underrated reason that House Republicans are reverting to small-government conservatism with their new majority. The question of whether that strain of conservatism is an electoral loser remains unsettled.

The Tea Party won big in House races in 2010, after all. It won big again in Senate races in 2014. Even in defeat in 2012, Mitt Romney managed a larger share of the national popular vote than Trump did in either of his two runs for president. And Romney was pitted against a talented incumbent, a steep climb for any challenger historically. Trump never had to face that challenge.

In 2016, after Trump shocked the world, it was easy to look back at 2012 and conclude that Romney/Ryan conservatism is unviable by comparison. But then Republicans lost the House in 2018. They lost the presidency in 2020. They lost the Senate in 2022 and underperformed so badly down ballot that they nearly failed to flip the House, an almost unheard of disappointment in modern midterms.

But what about “the missing white voters” who didn’t turn out for Romney in 2012 but did show up for Trump in 2016, you say? Aren’t they proof that Trumpy nationalism is the path to electoral glory?

Well, no, not if doing what’s required to win those votes ends up costing the GOP a larger number of votes in the suburbs. And not if it turns out that culture war rather than protectionist economic policies was the real secret sauce in Trump’s appeal to working-class whites. Maybe, all things considered, the missing white voters would have been fine with a traditional pro-business Republican as their champion so long as he proved himself more eager than Romney was to go on offense against liberals in cultural disputes. Remember, Romney-esque Glenn Youngkin actually outperformed Donald Trump among Virginia’s rural voters when he won the state’s gubernatorial race in 2021.

Did the missing white voters in 2012 really stay home because they feared a Vice President Paul Ryan would slash their Medicare? Or did they stay home because Mitt Romney was a cold fish with little zest for confrontational cultural revanchism?

If you’re an old-school Republican congressman, you might consider all of that and conclude that fiscal conservatism isn’t such an electoral liability after all. (True “true conservatism” has never been tried!) If it isn’t what the people crave, it’s at least something they might happily accept so long as it comes piled high with lots of messaging bills about “wokeness,” DEI, transgenderism, and so on.

To see what happens when Republican leaders do believe that conservative orthodoxy has become a liability, look at abortion.

The new House majority is moving two pro-life bills, one to require doctors to provide life-saving care to infants born alive after a botched abortion and the other to condemn vandalism of churches and crisis pregnancy centers. That’s not enough to satisfy anti-abortion activists, who’ve decided that 50 years of conservative rhetoric about leaving abortion to the states should now be jettisoned in favor of federal legislation to roll back the practice. But it’s more than enough for (relatively) moderate Republicans like Nancy Mace.

It may be more than enough for Donald Trump too, who warned his party last week that taking a hardline “no exceptions” stance to abortion cost the GOP votes during the midterm. A caucus as committed to the politics of confrontation as Kevin McCarthy’s new Republican majority would, one might think, support aggressive pro-life legislation right out of the chute to go on offense against pro-choice Democrats. But instead they’ve moved tentatively, focusing on the least controversial aspects of abortion policy.

Why? Because Republicans are broadly convinced that Trump is right. Being too hardline about abortion probably did cost them votes, not to mention Senate seats, in November. A political party will strain mightily to persuade itself and others that its core convictions are shared by the voting public even in the teeth of adverse election results. But every now and then a result is so clear as to be almost unspinnable. And so, quietly, the party adjusts its expectations of what’s legislatively feasible instead.

The GOP appears to have reached that point with respect to abortion. Faced with unambiguous evidence that aggressive pro-life policies mean electoral defeat, their inclination to confront, confront, confront has succumbed to a reasoned retreat. Because the evidence that draconian fiscal conservatism is a liability is less clear—again, contrast the GOP’s electoral record during the Tea Party era with its record under Trump—the urge to confront the left on that point persists.

It’s probably gonna cost ‘em. But some lessons will only be learned the hard way.

There’s one way short of electoral repudiation that the House GOP might be steered away from fiscally conservative brinkmanship and toward a more popular agenda of the sort Douthat imagines. (“A crime bill, a border security bill, a bill highlighting issues with military recruitment and readiness, reforms to academic funding and tax breaks and school standards that aim to weaken the elite-college cartel and influence the educational culture wars.”) A party leader with broad support could emerge who imposes ideological discipline from the top down, bringing Republican members of Congress around to his or her positions. Ronald Reagan shaped the Republican revolution of the 1980s. We’re waiting for another Reagan to help shape the next one.

It won’t be Trump. He’s past the prime of his influence and too invested in the politics of confrontation to steer the party away from it. He’ll support a debt-ceiling duel to the death for his own selfish reasons, because he knows right-wing primary voters equate brinkmanship with “strength,” because the economy tanking would be good for his reelection chances, and because he relishes chaos for its own sake. If fiscal standoffs with the Democrats end up hurting Republicans at the polls, well, he’s never cared much about the GOP winning elections anyway.

But what about the other guy in contention to lead the Republican Party circa 2025? You know who I mean. The one named … Ronald.

I wouldn’t get my hopes up for him either.

Bonnie Kristian is right that a President DeSantis would exert enormous influence over Republican orthodoxy on foreign policy. That’s even more of a muddle than Republican orthodoxy on domestic policy, leaving it ripe to be molded in the next president’s image. Presumably he’d lean hawkish, keen to demonstrate “strength,” but the isolationist trend among right-wing politics would give DeSantis latitude to maneuver. He could avoid confrontation abroad as he prefers.

But here at home? No chance. Arguably no one, Trump included, understands better than Ron DeSantis that popularity within the Republican Party requires relentlessly confronting the right’s domestic enemies. As such, it’s unimaginable that he’d discourage House Republicans from a politically and economically ruinous fight over the debt ceiling just because having that fight would be politically and economically ruinous.

Especially since, more so than most Republican politicians, DeSantis is hypersensitive to populist opinion. This is a guy so intent on staying on the good side of MAGA voters that he’s repositioned himself as a vaccine skeptic to win their favor. He surely knows by now that a majority of Republican voters oppose raising the debt ceiling. He’s not going to side against them and with Democrats by backing a clean debt-ceiling hike, especially while Trump is hooting at the House GOP to fight, fight, fight.

There go the people. He must follow them, for he is their leader.

In short, with either Trump or DeSantis in charge, the party will continue to operate like a feedback loop in which the leadership and the voters are forever looking to each other to provide some ideological clarity. Until a true ideologue captures the imagination of the GOP base and galvanizes the party around his beliefs, an uneasy coalition based on little more than confrontation may abide. The pre-Trump GOP didn’t offer much, but it could and did certainly offer confrontation around its pet issues. In the absence of party consensus on policy, it will reassert itself and give the people what they want.

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.