Dear Capitolisters,

I’d originally planned to do a “clip show” version of Capitolism this week, in which I—still technically on vacation—lazily listed some of my favorite or most popular/relevant columns (and charts!) from 2021. But the last couple weeks of holiday- and Omicron-related COVID-19 news have me thinking a lot about the question I asked back in January 2021: Would free(r) markets—i.e., minimal government regulation and subsidization, market pricing, free trade, etc.—have handled vaccine production, distribution, and uptake, and thus the pandemic, better than the U.S. government? As you’ll recall, even a hardcore free marketer like me was somewhat skeptical of a “pure” market approach, even noting some of the theoretical reasons why a top-down alternative may have been preferable. However, the last 12 months of U.S. public health bureaucracy boondoggles have increasingly radicalized (ha) me; now it seems clearer that a system with far (far) less government involvement, while surely messy and chaotic at times, would’ve produced far better results than what we’re experiencing today (which is, by the way, also quite messy and chaotic!).

Testing My Patience

Perhaps the biggest of these boondoggles still haunts us today: the continued regulatory blockade of—and executive branch errors regarding—at-home (“rapid”) COVID-19 tests. We discussed the testing situation at length back in September—noting then (1) the dearth of FDA-approved antigen tests (which are cheaper and faster than, and can be just as accurate as, lab-based “PCR” tests); (2) the numerous public health experts and economists begging the Biden administration to deregulate (lawfully) the process; and (3) the ominous-yet-obvious signs of avoidable future shortages. To be clear, I certainly wasn’t alone in making these arguments. Since then, the FDA has approved a few more rapid tests (still far fewer than European regulators, it must be noted), but—with the Omicron variant and holiday travel spiking U.S. demand—the testing situation here hasn’t improved and may have actually deteriorated.

Numerous stories of high prices and short supplies seem to have pushed President Biden last week to promise yet another round of top-down, too-late, industrial policy-style fixes (Politico counted five such promises since January), while still seemingly ignoring the solution—helpfully summarized by Harvard’s Michael Mina in the following Twitter thread—that’s been staring us all in the face for more than a year now:

As I noted around the same time, the most frustrating part of the United States’ continued lack of rapid test abundance is that this product isn’t complicated or novel like an mRNA vaccine (and thus potentially requiring government help to mitigate investment risk or correct a “market failure”). It’s simple and common, and—as Mina note—several large manufacturers around the world have ample production capacity and are just itching to serve eager U.S. customers but have been blocked by the FDA. These additional supplies almost certainly would’ve lowered U.S. prices too. Indeed, my Cato colleague Paul Matzko recently provided a real-world example of how simple FDA approval of additional tests can affect prices, tracking the declining prices of rapid tests on Amazon as a new competitor received FDA approval.

So maybe additional government subsidies for stockpiles and onshore production (the focus of Biden administration rapid testing efforts) could further boost supplies and lower prices, but the miserable U.S. testing situation’s cardinal sin wasn’t a market failure; it was a regulatory one that—as past FDA rejections of at-home tests for pregnancy or HIV show—has been with us for decades.

Indeed, the true extent and effect of this regulatory blockade was crystallized in a tremendous new report from ProPublica’s Lydia DePillis on how the FDA’s nonsensical (medical experts’ term, not mine) approval process stymied the dissemination of a cheap, effective COVID-19 rapid test—in March 2020. That antigen test, from MIT lab E25Bio, had quickly attracted millions in private funding—from venture capital and the Gates Foundation—and had a U.S. manufacturing facility ready to roll.

Meanwhile, a $666 million NIH program to accelerate the approval and production of new COVID-19 tests funded mostly PCR tests in 2020.

The antigen tests that did make it into the NIH program in the first three funding rounds— including one made by Quidel, a public company that multiplied its profits by tenfold in 2020 over the previous year— generally had to be processed in labs or required expensive analyzers.

One of few simple antigen tests to win government support, made by Maxim Biomedical, still hasn’t submitted an EUA application, according to chief operating officer Jonathan Maa. Another grantee, Ellume, was authorized for nonprescription home use in December 2020. But it took months to go into widespread production, and still costs $39, if you can find it.

In a darkly comedic turn, DePellis notes that E25Bio’s chief researcher, Irene Bosch, has since moved on to study rapid antigen testing in high-risk, low-income Chelsea, Massachusetts—using donated tests “from five manufacturers that had been authorized in Britain, Germany, India or Korea” but not in the United States (even though they’re about as accurate as the ones approved here). Bosch provides the killer quotes near the end: “I wanted to show to the world that an experimental device is just as good as any other already-approved FDA test. …. How do we flood the market with a $2 test that is as good as a $20? We’re doing it in Chelsea. We should be an example for the whole country.”

Yes, you should.

But It’s Not Just Rapid Tests

Unfortunately, the U.S. government’s frustrating, even counterproductive pandemic actions aren’t limited to rapid tests. I noted several prominent examples of these problems back in September and, with Omicron raging here, more are appearing every day. But here are a couple more big ones:

Therapeutics. Pfizer’s COVID-19 pill, Paxlovid, was so effective in large-scale clinical trials that they stopped the tests on ethical grounds (because it’d be unconscionable to design a study with a no-Paxlovid control group that got infected with the virus), but it still took the FDA about 40 days—almost a week longer than the EU’s regulator and with “controversial” speed –to approve it for emergency use. Similar issues apply to Merck’s (admittedly less-effective) therapeutic, which the U.K. approved in early November. And then there’s the very-cheap and common therapeutic called Luvox, which sat in regulatory limbo for weeks—a frustrating and absurd situation that even Vox called a “public health and communications failure.”

Though the U.S. has only about 65,000 courses of Paxlovid at the moment, millions more have been licensed around the world and are coming soon. In the meantime, one really must wonder how many American deaths (still averaging more than 1,000 per day) could’ve been prevented if drugmakers had been permitted to sell their COVID-19 products to eager and willing American consumers without official FDA signoff or even simply when other foreign regulators had done so. My guess is more than a few, but even one is too many.

Boosters. The FDA and CDC also thoroughly botched both the communications and approvals surrounding COVID-19 boosters, likely inhibiting uptake across the country (which remains depressingly low). It was evident over the summer (i.e., long before Omicron) that boosters would be safe and useful, if not necessary, yet our public health bureaucracy spent months debating eligibility and issuing confusing, sometimes-contradictory recommendations when a simple thumbs up/down safety review would’ve been more than sufficient during a pandemic emergency. Now, Omicron has boosted (pun!) the third jab’s value, but many Americans aren’t sure they want to get it (or simply can’t get it soon enough). And even the White House just admitted that “regulatory processes” stymied their (common sense) efforts to get Americans boosted earlier this fall. Indeed, as Harvard’s Jason Furman noted, “What is especially frustrating is that only two FDA officials have resigned on principle during the COVID pandemic. And the principle they resigned over: concern that booster shots were being approved for too many people too quickly.”

On this and so many other public health issues, it’s trolley problems all the way down.

Which Brings Us Back to Vaccines (and the State’s Vaccine Monopoly)

So I can’t help but wonder whether the government’s role as the sole regulator, buyer, and distributor of both vaccines and boosters has—along with related government mandates—heightened the politicization of vaccine uptake and thus vaccine hesitancy. (As an aside, this gets to perhaps my biggest miss of 2021: my overly-optimistic take in February that we were turning the corner and emerging from the pandemic. I was right about the economic recovery, but underestimated the number of adults who’d remain hard-core vaccine refuseniks and how new variants would affect public health and economic issues through the fall.)

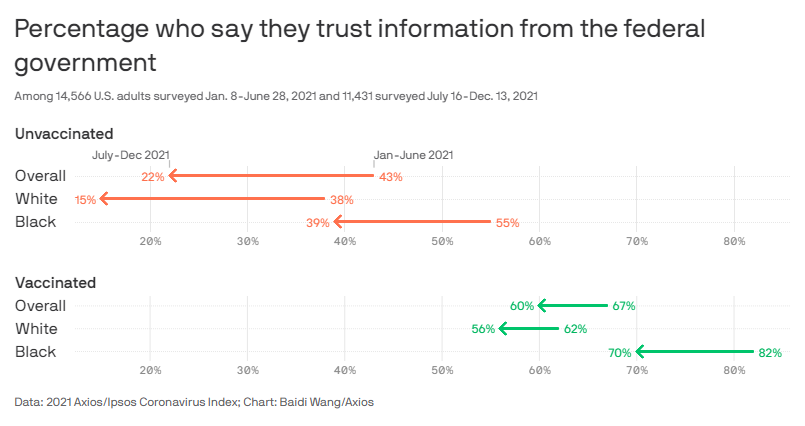

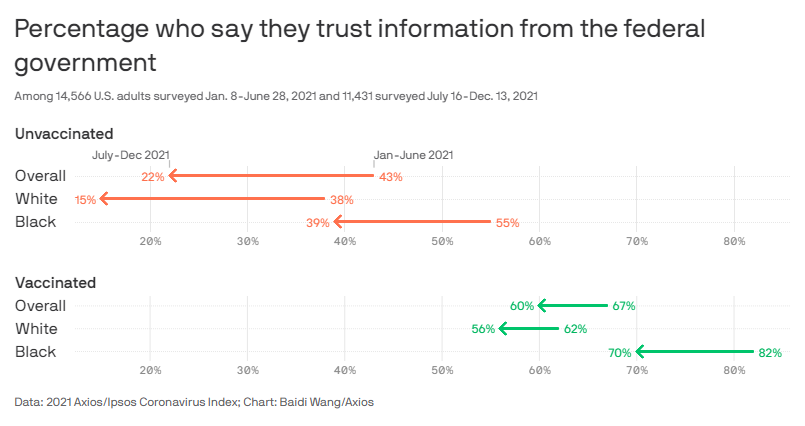

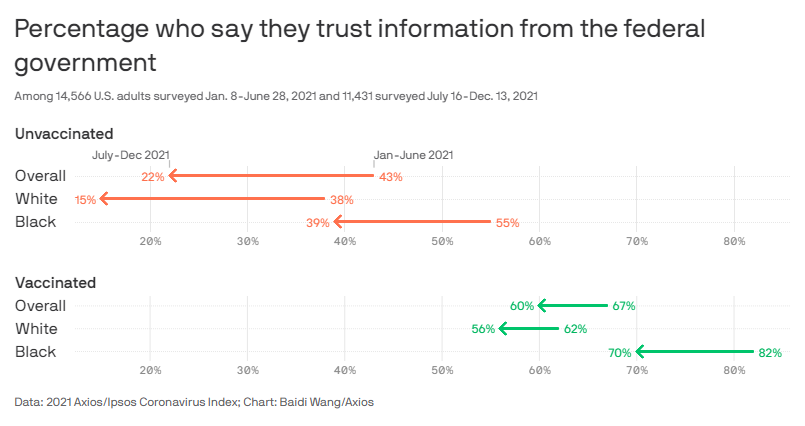

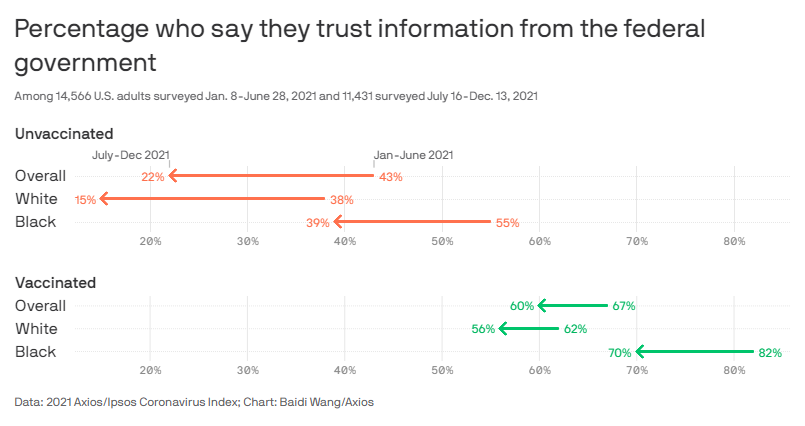

That we live in a bitterly, often-irrationally partisan age, of course, isn’t necessarily* the government’s fault, but it’s the reality we face. And numerous anecdotes and polls show quite clearly that partisanship and respondents’ trust of the government correlate strongly with vaccine skepticism:

Limiting the government’s role in the vaccination process could have turned the Biden (or Trump) vaccine into simply “the vaccine” and perhaps also disconnected it from all those other bureaucratic missteps, thus potentially decreasing skepticism and resistance among millions of vaccine holdouts.

State mandates, meanwhile, may have exacerbated these concerns. According to a recent New York Times analysis, for example, the requirements have had little effect on vaccine uptake and may, in fact, have slowed things down as skeptics became more defiant in the face of government force: “In most locations, the number of adults with at least one shot grew at a slower pace after states and cities announced mandates than it did nationwide in the same time periods.”

The federal vaccine mandate raises similar concerns (not to mention several others), as my Cato colleague Gene Healy recently explained:

For years, the theory was that vaccine hesitancy was mainly a problem of information: give people the good news and they’ll queue up for the jab. But as Sabrina Tavernise explains in the New York Times, recent research suggests it’s more complicated. When epidemiologists joined with social psychologists to study the issue, “what they discovered was a clear set of psychological traits offering a new lens through which to understand skepticism.” Among those traits is one dubbed reactance, a deep‐seated aversion to loss of threatened freedom. “According to this model,” the APA Dictionary explains, “when people feel coerced into a certain behavior, they will react against the coercion, often by demonstrating an increased preference for the behavior that is restrained, and may perform the behavior opposite to that desired.” It’s a healthy impulse in general—though emphatically not in this particular case.

Like it or not, though, mandates can backfire because people don’t want to be told what to do, particularly by someone they hate—and a good many in the target group hate the president more than they hate their boss. Add to that the fact that what the press has been calling a “vaccine mandate” is actually a “test or vax mandate.” Under the proposed emergency temporary standard, workers determined to avoid the needle will have an out that allows them to keep their jobs. For many high‐reactance, Biden‐hating vaccine skeptics, that’s going to look like the most attractive option.

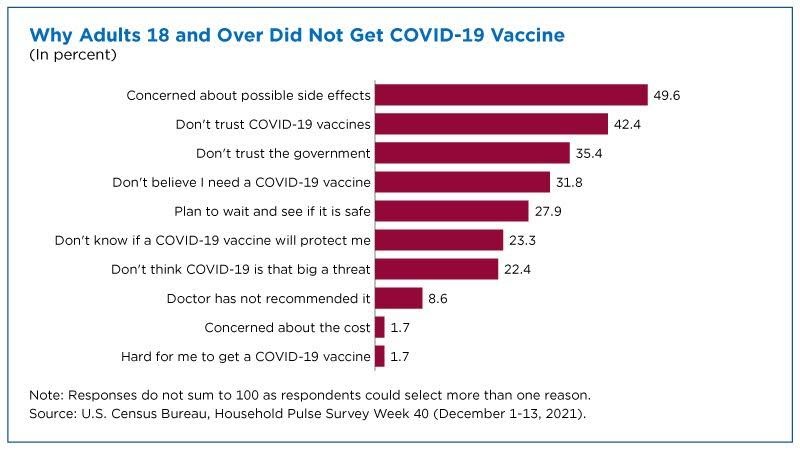

For many individuals already skeptical of government action ( spoiler: It’s a lot more people than you might think), a state mandate that you take the state’s vaccine that was approved by the state (yet profits giant multinational drugmakers) might not be a very exciting proposition! And no amount of charts and data is going to change their mind, not even crystal clear ones like this:

As of today, CDC data show that only 73 percent of American adults (18+) have had two vaccine doses (and that’s probably an overestimate), and far fewer have received boosters—despite volumes of evidence showing the mRNA vaccines’ safety and continued efficacy against severe COVID-related illness or death, even variants like Omicron. They’re free, widely available, and inarguably the most scrutinized drugs ever developed. Yet vaccine status has become a bizarre partisan marker, with resistance among holdouts seemingly getting stronger regardless of the facts on the ground. Would acceptance and uptake have been better if the government’s role were more limited (e.g., to checking basic safety and/or awarding prizes for development), and vaccines (and tests and therapeutics) were simply sold at U.S. retail outlets like any other boring medication? Would a system of free choice and persuasion – messy, sure, but also more efficient, dynamic, and robust – have been better at getting needles in arms than kludgeocracy, industrial policy, and coercion?

I was somewhat skeptical back in January, but not so much today—especially given all of the other government misfires and the fast-moving Omicron variant today (which has Substacker Noah Smith—hardly a libertarian!—sounding like Hayek: “The question of whether we should ‘let ‘er rip’ is a bit beside the point— by the time our authorities decide what to do, it will already have ripped.”) Seems we really could’ve used some libertarians in the pandemic after all.

Maybe next year.

*Though we libertarians must note that a government involved in every aspect of our lives—health, education, consumption, employment, retirement, etc. etc.—almost inevitably ensures heightened politicization and partisanship.

Chart of the Week

The Links

Not a lot of links this week (vacation), but here are a few:

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.