Dear Capitolisters,

Last week, President Biden issued an executive order initiating a White House-led review of “key” global supply chains (including medical goods and semiconductors) that have been affected by the pandemic. The president’s timing was superb, as his new order was published on the same day as my new paper on pandemic-related supply chains and the federal government’s response thereto. That paper arose in response to claims from numerous politicians and pundits, including Presidents Trump and Biden, that pandemic-related shortages in the spring of 2020 had revealed major weaknesses in America’s “economic resilience”—weaknesses caused by past U.S. policies and demanding new federal government action.

Surely, these claims have a nugget of truth: Global supply chains and a nation’s openness to trade and investment inevitably involve a risk that a “shock”—war, pandemic, natural disaster, etc.—hits the world or certain key nations and roils domestic supply. And such issues definitely arose a year ago, when factories shut down, container ships sat empty at port, and our grocery store shelves were empty. Such is the nature of a once-in-a-lifetime shock to global supply and demand. Things tend to get messy.

However, the story of COVID-19 and our supply chains doesn’t end in April 2020, even though many folks in Washington are still today acting like it did. Since then, governments and markets have responded, and they’ve done so using both global supply chains and the significant industrial capacity that—contra the conventional wisdom—still exists in the United States. These experiences reveal that federal government attempts to reshore supply chains raise their own risks, and that freer markets can bolster U.S. resiliency by increasing economic growth, mitigating the impact of domestic shocks, and maximizing flexibility in times of severe economic uncertainty. This argues for a different approach to achieving real resiliency—an approach based on the open and flexible policies that America does best.

The Reality of American Manufacturing

As we discussed a few weeks ago (and I explained at length here), there’s little evidence of systemic weaknesses in the United States’ “industrial capabilities,” and the U.S. manufacturing sector remains among the most productive and attractive in the world. (It’s also booming right now.)

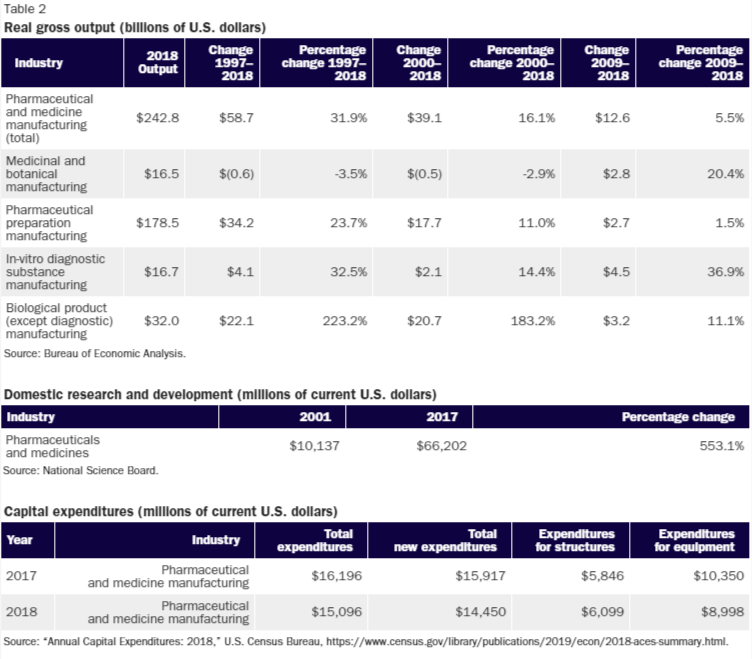

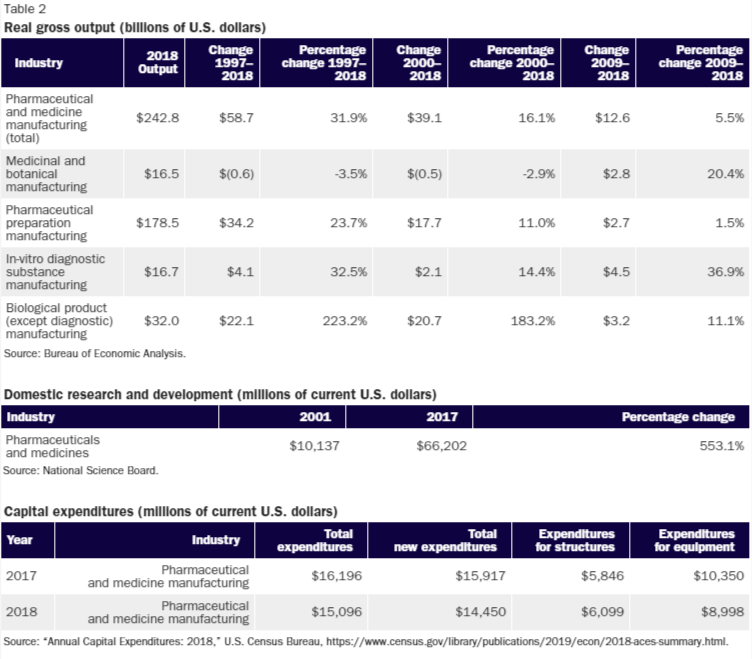

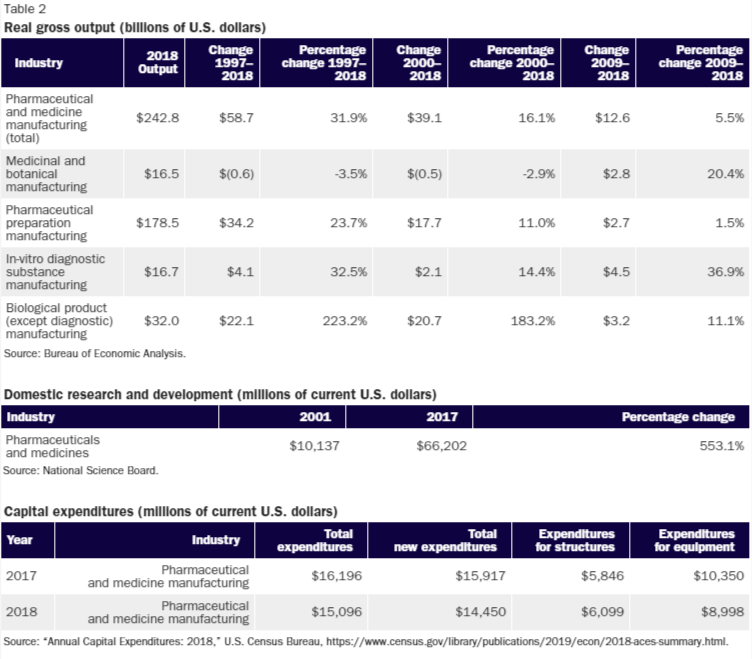

Similar strength is found in the manufacturing industries most closely associated with pandemic resiliency—including medical goods and semiconductors. On the former, numerous studies of medical equipment and supplies (ventilators, masks, etc.), soaps and cleaning products, and drugs show healthy domestic industries with expanding production and investment (feel free to click through my new paper for links). Pharmaceuticals—a target of Biden’s new order and past Trump administration efforts—are especially noteworthy:

A 2020 McKinsey report notes that the United States is home to more than 500 pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities—among the highest concentrations in the world—and that the biggest risks to those supply chains are political, not economic. Just this week, Merck reportedly agreed to use its substantial U.S. manufacturing capacity to produce Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine, potentially doubling J&J’s output.

Even our so-called “dependence” on China has been greatly oversold (and, no, it’s not the source of 80 percent of our drugs). We do need better data on pharmaceutical inputs (i.e., active pharmaceutical ingredients, or “API”)—something that a forthcoming National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report commissioned by the CARES Act should resolve—but the evidence we have does not indicate a serious problem demanding urgent government funding, such as the $765 million loan offered to Eastman Kodak Company to help it turn into a pharmaceutical company.

Semiconductors tell a similar story: Domestic semiconductor manufacturers generated almost $65 billion in output in 2018 and are major exporters, and the United States is a large and growing spender on capital goods and R&D ($71.7 billion in 2019). The Semiconductor Industry of America adds that there are commercial semiconductor manufacturing facilities in 18 states, employing more than 240,000 Americans, and the largest share (44 percent) of U.S. companies’ production still occurs at home (while only 5.6 percent is in China, whose industry is still struggling). While subsidy-seeking semiconductor CEOs like to point out that U.S. producers share of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity is smaller today (at 12.5 percent) than it was in 1990, they conveniently ignore that, as the Hudson Institute’s Riley Walters explains, U.S. production capacity has “nearly doubled since then to 3 million wafers a month.” (Spoiler: The U.S. industry isn’t shrinking; the global pie is just getting bigger.)

Surely, U.S.-based Intel has struggled over the last year or so, announcing delays to its most advanced chips, but it’s hardly in dire straits: Last year Intel spent $15 billion in capital expenditures and had more than $60 billion in revenues plus a whopping $17.5 billion in free cash flow. Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Defense just partnered with GlobalFoundries to make secure chips “for some of DoD’s most sensitive applications” at the company’s plant in upstate New York. (Major foreign chipmakers Samsung and TSMC are also planning to build factories in the United States, and both companies are unsurprisingly lobbying for “huge” federal subsidies to do it.)

Subsidy-fishing aside, the data show that this simply isn’t a dying domestic industry, and the U.S. government shouldn’t be in the business of socializing Intel’s business mistakes or throwing taxpayer money at cash-flush foreign chipmakers who’d build here “even without major incentives.”

And Then What Happened?

Just as important, there is now plenty of data showing that domestic producers and supply chains have weathered the pandemic as well as could be expected, given 2020’s massive and unforeseen shocks to global supply and demand. I covered medical goods at length a few weeks ago, so I’ll just reiterate that a December 2020 U.S. International Trade Commission report found that U.S. manufacturers and global supply chains responded quickly to boost supplies or make new drugs, medical devices, PPE, cleaning supplies, and other goods, and that the pharmaceutical, medical device, N95 mask, and cleaning products (including hand sanitizer) industries were particularly “resilient” (in the ITC’s own words). There’s also plenty of anecdotal evidence of U.S. investors, producers and importers moving quickly to produce or supply high-demand PPE and other goods during the pandemic. Now, we have members of Congress writing President Biden about a glut of U.S.-made PPE:

Domestic production capabilities for essential products like isolation gowns, N95 masks, testing swabs and other critical products have grown exponentially since the beginning of the crisis. However, regrettably, we have too many manufacturers in our states and across the nation that have capacity but no orders to supply.

Finally, do you remember that crisis regarding foreign governments restricting exports of hydroxychloroquine (ha) and other drugs in spring 2020? Well, it never materialized:

The current global semiconductor shortage, meanwhile, appears less about American manufacturing “resiliency” (or lack thereof) and more a case of mistaken corporate planning, pandemic-crazed markets, and potentially misguided U.S. trade policy. For starters, various reports show that the auto industry’s semiconductor problems are in large part a “self‐inflicted wound”:

Auto-parts suppliers in February and March reduced orders for electronics, according to industry executives, betting that large volumes wouldn’t be needed well into the future.

Some companies halted shipments by invoking legal clauses in their contracts that let them change terms because of circumstances beyond their control, such as natural disasters, said Ganesh Moorthy, CEO-elect of Microchip Technology Inc., an auto-chip supplier based in Arizona. The car-industry’s thinking, he said, was that demand wouldn’t rebound to its earlier peak for years.

Chip makers chose not to stockpile parts and wait for car makers’ orders—a decision made easier by surging demand from companies that benefited from the work-from-home era fueling sales of laptops, servers, smartphones and other electronics.… [T]he car industry largely operated as if electronics suppliers were at its mercy, said Michael Schallehn, a Bain & Co. partner specializing in semiconductors. “Normally, when they are calling on their suppliers, everyone is excited about the large volumes,” he said. “But compare that to the billions of smartphones and PCs that are being sold.”

Oops. Meanwhile, not all automakers are suffering—Toyota, for example, wisely stockpiled chips—and North American producers are actually among the least‐affected automakers in the world:

There’s also the small problem that automakers primarily need low‐margin commodity chips made by older equipment (not the bleeding‐edge chips/equipment that the U.S. military needs or that the federal government wants to subsidize): “As such, the necessary tools are hard to come by, and the price of old gear on the secondary market ‘has gone through the roof,” according one industry expert.

Finally, Georgetown’s Abraham Newman points out that the U.S.-China trade dispute also reduced global supply of the chips that automakers and other companies need. As he notes, the Trump administration’s “effort to limit Chinese advances in semiconductors” (via restrictions on exports to China’s largest chipmaker SMIC) “took a major producer of semiconductors basically offline as companies avoided using their product” (thus reducing global supply) and caused companies to “hoard chips to evade U.S. sanctions” (thus increasing demand). One can debate whether U.S. tech policy toward China here is warranted, but we should nevertheless be clear-eyed about its impact—and thus the efficacy of certain alleged “solutions” to the chip shortage.

Why Skepticism About Supply Chain Nationalism Is Warranted

If all of this sounds like a complicated and ever-evolving situation, it is. And that’s one of several reasons why we should be skeptical of simple solutions like “renationalizing essential supply chains” to achieve economic “resiliency.”

First, self‐sufficiency policies would produce all sorts of distortions. Most notably, there’s the problem of maintaining pandemic‐level capacity in normal times. The USITC calculated that in 2020, for example, the United States used many times the number of N95 masks, medical gowns, surgical masks, and other essential goods that were used in 2019. Maintaining that much excess capacity in times of normal demand is extremely costly (profitability often kicks in at around 80 percent capacity utilization), and running at that level in non‐pandemic times would produce a global glut—exports of which are certain to cause new trade tensions. Indeed, as noted above, we could already be facing a glut of American‐made PPE, and foreign governments are already speaking out about other nations’ pandemic‐era subsidies.

The second problem is U.S. policymakers’ inability to know which products to target both during and after the pandemic. (Hayek’s classic “knowledge problem.”) Ventilators, for example, were on no one’s radar before COVID-19, and then became a hot commodity in March 2020. So the Trump administration invoked the wartime Defense Production Act (DPA) to force domestic manufacturers like GM and GE to make ventilators. (Yay, problem solved!) Only one small hiccup: Doctors subsequently determined that ventilators were not as critical as once thought, yet producers continued to churn them out under government orders, leading to reports of the goods “piling up” in a strategic reserve or being donated to “countries that don’t need or can’t use them.” According to the USITC’s December 2020 report, other DPA‐funded medical goods production won’t come online until late summer or thereafter, when the pandemic may (hopefully) have subsided. Will we permanently subsidize that new capacity?

Regardless, past government interventions and independent company efforts to expand operations or enter the medical goods market—see, for example, Mark Cuban’s new, subsidy-less generic drug company in Dallas—raise questions as to whether additional government action is really needed or whether the risks that we thought we discovered last year will be with us this year and next. Indeed, by the time U.S. policymakers decide to intervene again in the U.S. market, it will look much different than the one on which they based their decision and will likely change again by the time any government‐supported production comes online. And as China’s failed attempt to restrict “rare earth” minerals hopefully taught us a decade ago, markets don’t just sit still and wait for crises to occur (and they’re moving once again).

Third, future government interventions could have political, rather than economic, motivations. The poster child here is the Trump administration’s doomed subsidies to Kodak, which reportedly resulted from high-dollar lobbying and an eye toward Trump’s re-election. But Kodak’s not alone. According to a July 2020 Congressional Research Service report, for example, the Department of Defense invoked the DPA to give hundreds of millions of dollars, appropriated under the CARES Act to fight COVID-19, to politically connected industries (shipbuilding, semiconductors, space‐based defense, aviation, microelectronics, rare earth mining, etc.) that were—at best—tangentially related to the pandemic. The report adds that these and other pandemic-related DPA actions lacked transparency and accountability, led to the reassignment of one U.S. official, and were opposed by several House committees because they were not, as Congress intended, “reserved for health and medical countermeasures.”

Finally, there is the very real risk that supply chain nationalism would make the United States less, not more, resilient. As I discussed in my recent paper on manufacturing and national security, nationalist policies intended to boost “essential” industries—for steel, ships, machine tools, semiconductors, and other “essential” goods—have a long track record of high costs, high risks, failed objectives, and unintended consequences. In case after case, the protected industries did not emerge stronger or more resilient—in fact, just the opposite.

Furthermore, protectionism often undermines resiliency by weakening a country’s economy and manufacturing sector—a conclusion supported by decades of research on tariffs and other forms of economic nationalism. Economists have come to similar conclusions in the context of COVID-19: A November 2020 analysis, for example, found that the economic costs of “localizing” global supply chains for medical goods would hurt the economy yet also prove unable to insulate countries from a pandemic‐induced economic shock. Manufacturers who used imported inputs fared worse when their supplier markets were hit by COVID-19 but fared better when their own home market was hit. This conclusion echoed an earlier paper, which found that “renationalization” of supply chains would generally not improve a country’s overall economic performance after a global pandemic.

That may sound odd, but it actually makes sense: Reshoring supply chains might insulate U.S. producers and consumers from external shocks like foreign wars or natural disasters, but those same policies amplify shocks that are primarily domestic (not to mention lowering economic growth and output overall). And this very risk just emerged with respect to semiconductors and the recent winter storms in Texas: Several U.S.-based manufacturers were forced to idle production capacity, thus exacerbating the very chip shortage that nationalists have blamed on “globalization.” This also happened in other protected/nationalized sectors during the pandemic, such as pickup trucks (imports of which face a 25 percent tariff), where domestic supply has been shorter than it has been in more open parts of the same industry (e.g., small cars, which only face a 2.5 percent tariff).

By contrast, extensive literature ties trade openness to improved economic performance more broadly. A 2018 paper summarizing the research on the long‐run, overall gains from trade for the United States calculates total average gross domestic product (GDP) gains of 1.1 percent per year due to increased product variety, lower prices, and higher productivity caused by imports and trade‐induced creative destruction. Other studies have shown similar benefits for the U.S. economy.

Overall, the evidence and analysis refute current arguments that economic nationalism would bolster the U.S. industrial base (and thus national resiliency). Instead, American protectionism has been repeatedly found to weaken the U.S. manufacturing sector and the economy more broadly. And in most industries, the best way to prepare for a pandemic is to diversify, not re-shore, suppliers, while maintaining significant onsite inventories in case of emergency—something multinational companies are already (and unsurprisingly) doing in response to last year’s supply chain chaos. Where those policies prove inadequate, government stockpiles can step in. But in no case is widescale “repatriation” a good idea.

Summing It All Up

Economic openness and global interdependence risk importing economic shocks—including pandemics—into the United States, roiling supply chains and disrupting our lives. However, this same openness can promote stability and improve the nation’s resilience in times of national emergency. Nationalist policies, meanwhile, present a far greater risk to our ability to withstand and respond to economic shocks—even when such policies are implemented on security, rather than purely economic, grounds.

It’s incredible (or depressing), honestly, that these lessons still haven’t been learned by various politicians and pundits over the last year. The vast majority of the hysteria we heard about empty store shelves and the failures of globalization proved meritless—instead reflecting a single, shocking moment in time that markets, companies, and governments mostly addressed in a matter of months (“seemingly out of nowhere”). Today, some of the biggest impediments to our economic recovery are U.S. trade restrictions, not “free market fundamentalism” or whatever.

Meanwhile, Pfizer and BioNTech were quietly working on their miraculous COVID-19 vaccine, leveraging Pfizer’s substantial pre-existing U.S. manufacturing capacity, multinational research teams stocked with immigrants, global capital markets and supply chains, and a logistics and transportation infrastructure that had developed over decades to deliver those “cheap consumer goods” that the populist punditocracy loves to hate. The companies went from concept to final delivery of millions of vaccine doses in about nine months—just as their management boldly predicted last April. Surely, some state support (e.g., grants for previous mRNA research and vaccine purchase commitments) was involved, but the Trump administration’s contract with Pfizer expressly excluded from government reach R&D, clinical trials, and manufacturing supply chain issues (i.e., “activities that Pfizer and BioNTech have been performing and will continue to perform without use of Government funding”). Thus, even the uber-nationalist Trump White House realized that government attempts to “nationalize” and micromanage the vaccine’s development and delivery would have delayed—if not thwarted—those processes, costing numerous American lives along the way.

When time was of the essence and success really, really mattered, they just got out of the way. And it worked.

It’s a wonderful lesson—one that policymakers still stuck in April 2020 may never see.

Chart of the Week

“Some economists say a shrinking workforce threatens China’s chances of overtaking the U.S. as the world’s largest economy” (source)

Bonus Chart of the Week

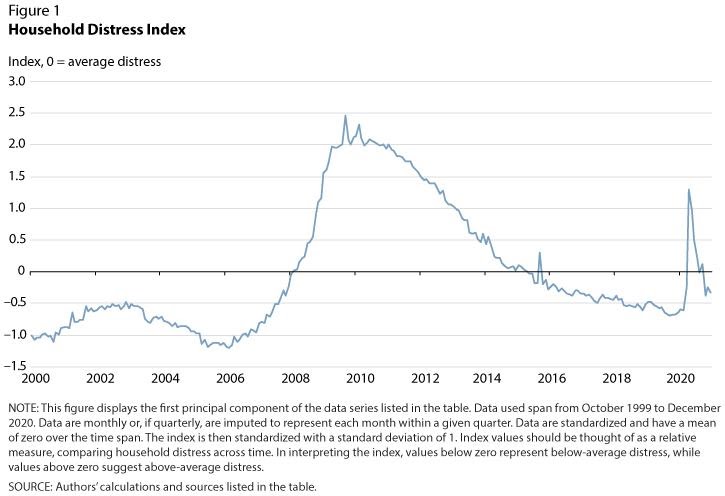

“The current level of household distress is below average compared with the past 21 years, which includes the Great Recession and its protracted effects”—St Louis Fed

The Links

Facebook has competition. (More on Dispo)

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.