Dear Capitolisters,

Recent events have me thinking about math. Trust me, as a guy whose last formal math course came in high school, I’m as surprised as you are, but the summer’s COVID-19 events have really hit home just how important an understanding of numbers and basic math concepts is to public policy and life more broadly, and just how innumerate (i.e., lacking those important things) we Americans collectively are. So today’s newsletter will take a slight detour from our usual deep-dive wonkiness to explore our innumeracy and why it matters, especially right now.

Our Innumeracy, Explained

To be clear, when I say “innumeracy” here, I’m most definitely not talking about someone—like me!—who lacks a thorough, formal understanding of advanced math or statistics concepts. Instead, this is about two interrelated—and far more basic—things: First, and as helpfully explained in this 2017 Wall Street Journal piece, is many people’s simple, biological inability to grasp large numbers and put them in the right context:

Here’s a brainteaser. Take a sheet of paper, and draw a line with the endpoints 0 and 1 billion. Then place a tick mark on the line where 1 million should appear.

A typical person will place the mark too close to the middle. But that’s where 500 million should go.

“About 40% to 50% of the people tested get it terribly wrong, and when they get it terribly wrong, they get it terribly wrong pretty much all of the time,” said David Landy, a cognitive scientist at Indiana University who studies mathematical perception and numerical reasoning.

In general, study after study shows that many people just struggle to grasp really big—and really small—numbers.

Second, a lot of people lack an understanding of basic math concepts and related reasoning skills. Again, I’m not talking about AP calculus or even freshman algebra here. Instead, this is about Americans constantly being presented numbers that appear to be big or small (or scary or benign, and so on), yet not taking—or not knowing to take—the next step to consider what those numbers actually mean in the specific context at issue and whether we actually need more information to judge their importance. Maybe, for example, a certain figure we see on social media—say, $10,000 or 75 percent—is a really big deal, but it’s often impossible to know without more information. And it takes a certain rudimentary understanding of math (numerators and denominators, timeframes, sample sizes, etc.) to know whether essential information is missing and that we should refrain from judging and sharing (or, in the case of media and government officials, reporting) it until we do.

Why Innumeracy Matters

I could go on a rant here about how both of these math problems reflect the fundamental failures of America’s public education system, but we can leave that for another time. Instead, we’ll today just accept this innumeracy as a given and explore why it matters for public policy and life in general. The above Journal article gets at the issue:

Big numbers befuddle us, and our lack of comprehension compromises our ability to judge information about government budgets, scientific findings, the economy and other topics that convey meaning with abstract figures, like millions, billions and trillions.

We understand how to count that high. We just have trouble conceiving what the figures mean. Yet humongous numbers pepper the news, and as citizens, we are asked to make sense of the material.

The most prominent recent examples of these difficulties arise in the case of the pandemic and public health policy. Over the last 18 months or so, we’ve been bombarded daily—by reporters, experts (real and imagined), colleagues, friends, and family (especially family)—by context-free figures that are often objectively worthless and, even worse, likely to elicit in many Americans precisely the wrong subjective reaction. And a few bits of recent vaccine-related news underscore just how rough the current situation is. For starters, NBC News reported back in July that the United States had experienced more than 100,000 breakthrough cases (i.e., vaccinated Americans who test positive for COVID-19)—a stat that was then amplified by numerous news outlets and shared by concerned folks around the country (and those with, ahem, less altruistic motives). But what many people failed to do—at least not in headlines or ledes—is explain just how tiny a percentage of total cases this really is:

This type of reporting and commentary is depressingly common—I seriously cannot tell you how many times over the last year I’ve said the word “denominator”—and it’s a failure of both the people reporting the figures and news consumers who don’t recognize the problem and demand the reporting be more informative.

Similar things have happened now with the vaccines and Delta variant, in the process revealing two common mathematical errors that everyday folks like you and me might make but serious public health officials and reporters most definitely shouldn’t be. First, widely shared numbers about breakthrough infections in the United States, Israel, Iceland, the U.K., and elsewhere often suffer from the “base rate fallacy” (or base rate bias), meaning that the figures don’t include or consider the group from which the numbers are derived and that group’s essential characteristics (here, vaccination status). One notable example of this came up in The Morning Dispatch a few weeks ago: a study on which the CDC reportedly based its new Delta-related masking guidelines (out of fear of increased infection and transmission) revealed 469 COVID-19 cases in Provincetown, Massachusetts, between July 3 and July 17, a large share (74 percent) of which occurred in fully vaccinated individuals (mostly with Delta). However, these topline results were at risk of being misinterpreted or abused—and thus freaking out large swaths of the country or emboldening vaccine skeptics—without additional context about who was getting infected:

The study is significant, in that it shows fully vaccinated individuals are more capable of infecting others once they have a breakthrough infection themselves than previously understood. But because it… is missing a denominator for reference, it doesn’t say much about the likelihood of these breakthrough infections.

Ingu Yun, a retired doctor, was in Provincetown that weekend, and shared some criticisms of the CDC study in a Medium post that was subsequently endorsed by Dr. Bob Wachter, the chair of University of California San Francisco’s Department of Medicine, and Dr. Monica Gandhi, a UCSF infectious disease expert with whom we spoke last week. Yun noted that approximately 95 percent of very liberal Provincetown has received at least one vaccine dose, and noted it is a resort town on which tens of thousands of people descend to pack themselves into poorly ventilated bars and clubs every day.

Similar examples of base rate errors—for vaccines and other aspects of the virus—pervade news outlets and, of course, social media, despite repeated efforts by experts and (some) journalists to correct them and explain the problem.

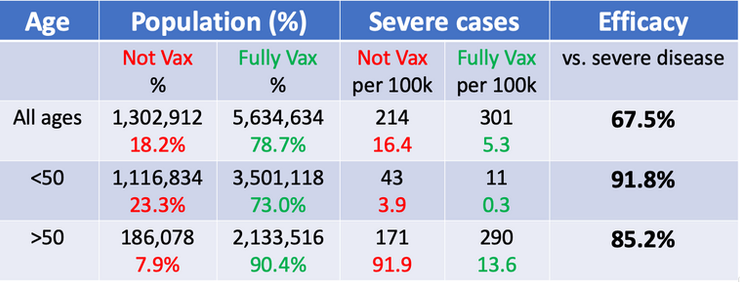

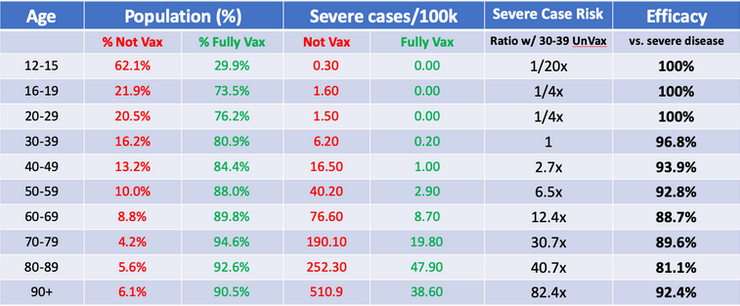

Second, we’ve seen recent data out of Israel—again showing a supposedly troubling increase in breakthrough Delta infections and serious illness—fall victim to “Simpson’s Paradox,” wherein a trend appears in one dataset but then disappears (or totally reverses) when the data are properly stratified. When all patients were lumped together, Israeli government data appeared to show that the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine wasn’t very effective in preventing illness and hospitalization—a result that again fueled both pandemic anxiety (calls for more masking, vaccine boosters, etc.) and vaccine skepticism. However, as thankfully explained by biostatistician Jeffrey Morris last week, these results have been misreported because they didn’t account for the vaccination status or age of the subjects involved. Because older people have both higher vaccine uptake and higher COVID-19 risk, failing to consider age substantially lowered the overall efficacy rate (thus, Simpson’s Paradox).

Using the same data that the Israeli government used, Morris reran the numbers to adjust for age and vaccination status, and—voila!—the vaccine’s strong efficacy reappeared:

Feel free to click through the blog post to check Morris’ math and get a better feel for Simpson’s Paradox (if you must), but here’s the key conclusion: “The bottom line is there is very strong evidence that the vaccines have high efficacy protecting against severe disease, even for Delta, and even in these Israeli data that on the surface appear to suggest the Pfizer vaccine might have waning efficacy.”

So the Israeli data that fueled days of angst turn out to be pretty good news—news many Americans unfortunately won’t read and, in fact, could ignore because they’re now convinced of the opposite.

It’s Not Just COVID

As the Journal notes, it’s not just COVID and public health where innumeracy problems arise, and perhaps nowhere is this clearer than federal tax and budget policy. Indeed, the first time all of this came to my attention was in 2009, when President Obama hilariously announced that his administration planned to cut a whole $100 million from the (at that time) $3.5 trillion federal budget. This elicited skepticism (and laughter) from a wide variety of journalists and economists, the latter of which wrote to put the tiny cut in proper scale. There was even a viral video:

Other commentators, however, noted at the time that Obama’s plan may have seemed silly but was actually shrewd (albeit cynical), as many Americans will hear that $100 million figure and, thanks to good ol’ innumeracy, think it’s a big deal. As the Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl explained back then:

So why bother? Because it may enhance the president’s “budget-cutter” image. Seriously. President Obama has reportedly been working closely with noted behavioral economists, and their studies have shown that most people are “insensitive to scope,” meaning they are not very good at putting large numbers in their proper context. People will react about the same to a policy proposal whether the cost/benefit is $10 million, $10 billion, or $10 trillion. Consequently, the $100 million cut may seem huge to many voters.

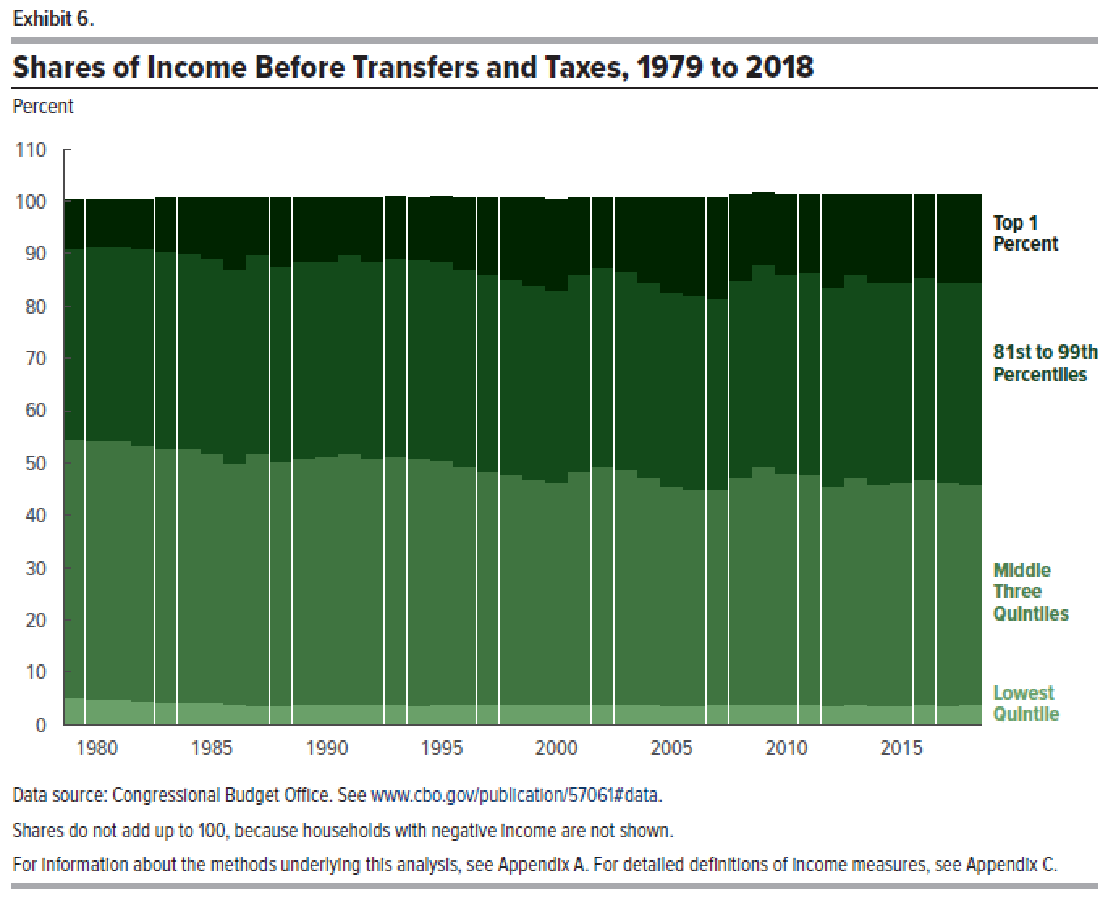

That’s a silly (and old) example, but there are plenty more. On the left, for instance, Progressive Democrats’ routinely insist that we can pay for all sorts of federal programs—free college, Medicare for All, and so on—by simply taxing “billionaires.” Yet, as Reason’s Nick Gillespie calculated earlier this year, this proposal fails even the most basic of arithmetical scrutiny:

There are 724 American billionaires worth a total of $4.4 trillion, according to Forbes. It’s a list that includes far-out space nuts like Bezos and Musk, entertainment moguls like Steven Speilberg and Tyler Perry, and lawyer-in-training Kim Kardashian. If it were somehow possible to liquidate all of that wealth without causing a market crash that would obliterate much of it in the process, we could cover roughly half a year of combined local, state, and federal spending.

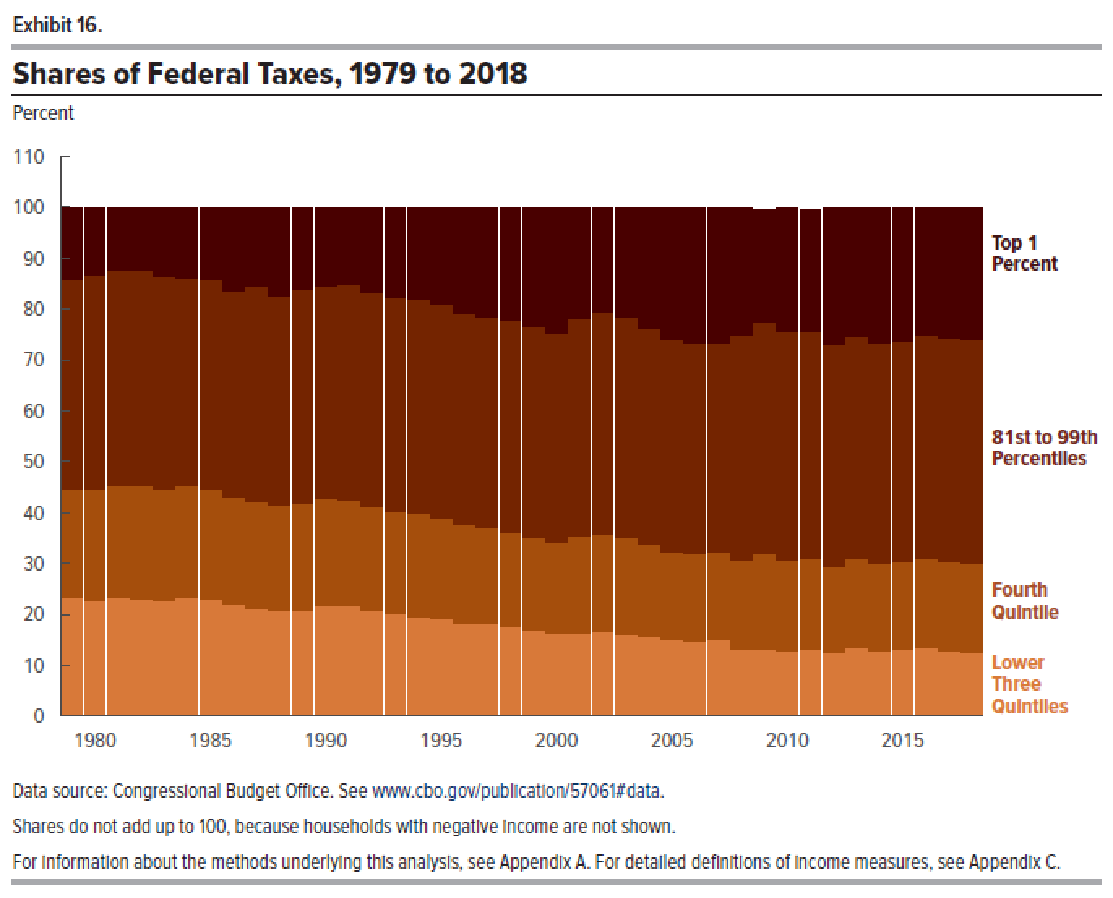

Even expanding the confiscation to millionaires, moreover, the job’s not getting done. As Riedl calculated in 2020, for example, a 100 percent tax rate for income higher than $1 million, with no tax deductions, would raise only $1.1 trillion per year (or $3,000 per person annually)—a lot of money, sure, but not even enough to balance the long-term budget, no less finance a bunch of new, big-ticket spending programs. Progressives often seem not to know or care.

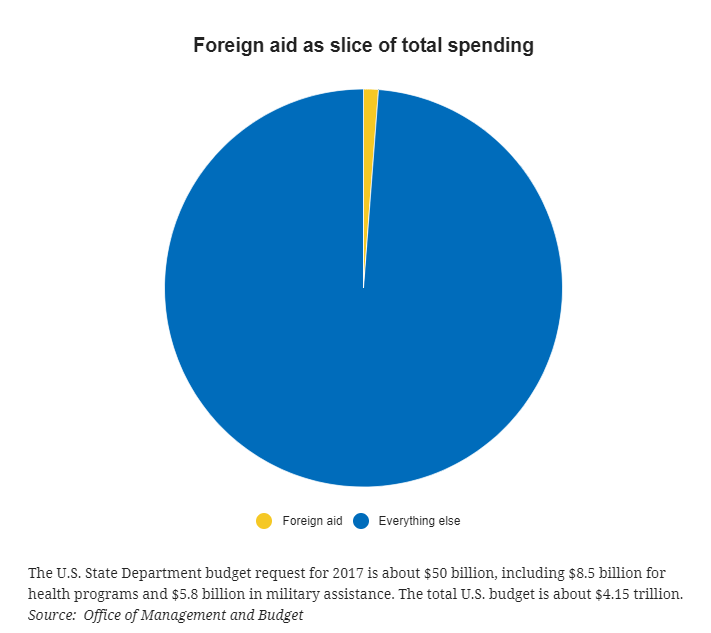

Republicans have their own math issues, too, of course. For example, GOP presidential candidates have routinely claimed that they can make a meaningful dent in ever-increasing federal spending by cutting foreign aid, but it has historically hovered around only $40 billion (i.e., less than 1 percent of the federal budget). Thus, while there may be good reasons to reform U.S. foreign assistance programs, the entire aid budget could be cut and do essentially nothing to our fiscal trajectory.

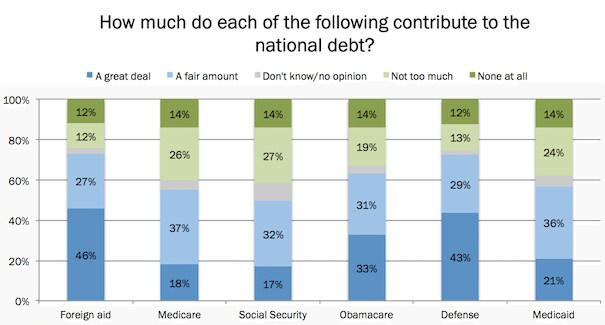

So why do Republican politicians keep bringing this up in the budget context? Well, perhaps it’s because—as noted by the Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell back in 2017—many voters in today’s GOP actually believe that foreign aid is a big driver of U.S. budget deficits: “63 percent of those who say they voted for Donald Trump in the 2016 election believe foreign aid contributes a great deal to national debt; just 33 percent of Clinton voters agree. (The shares for self-identified Republicans and Democrats are 57 percent and 34 percent, respectively.)”

Other polls have shown that voters routinely believe that foreign aid comprises as much as 25 percent (or more) of the federal budget. So when Trump or another Republican proposes to cut “billions in foreign aid” to address America’s debt problems, to many innumerate partisans it really seems like a big deal.

It isn’t.

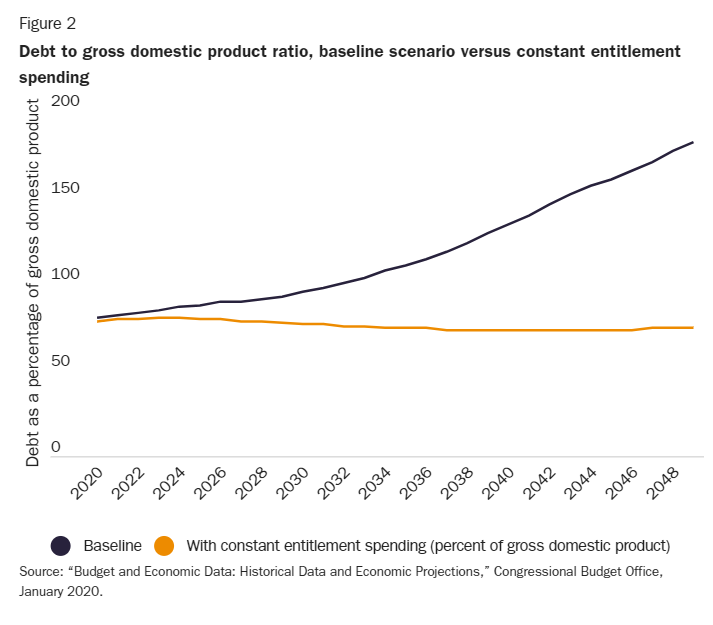

Finally, Rampell’s column hits on an important and bipartisan source of budgetary innumeracy: entitlements, which actually do drive the U.S. fiscal situation—unbeknown to many Americans (see poll above). As explained in a 2020 paper by my colleague Jeff Miron, U.S. entitlement spending really is the entire debt ballgame (and nothing else comes even remotely close). In fact, he shows that, if you simply reformed Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security to grow at the same rate as U.S. GDP, the United States’ long‐term debt burden (debt as a share of GDP) stabilizes:

Yet all of this is lost on many Americans, who place a high priority on curbing the federal debt, yet—often in the same poll!—want to expand entitlements and (of course) not pay any more in taxes.

(At one time, this kind of basic entitlement math was a pillar of the Republican Party, but … not anymore.)

Summing It All Up

Pervasive innumeracy has significant implications for our daily lives and public policy. Most obviously, a person’s inability to determine whether a certain number actually means what he thinks it means can encourage him to make bad decisions. This, of course, applies to personal cost-benefit assessments about whether to take a COVID-19 vaccine, thus affecting the person and his family/community, but there are plenty of other real-world situations in which basic math literacy matters: See, for example, recentresearch on state lotteries disproportionately harming lower-income Americans who spend more of their paychecks on lottery tickets, often because of financial illiteracy and innumeracy (which can make it harder to evaluate risk and correctly perceive probabilities). Similarly, Americans may incorrectly decide to support or oppose a policy (or policy reform) based on a faulty understanding of how it affects their personal or political priorities, such as reducing the federal debt. Maybe, for example, foreign aid is actually a good and fiscally-insignificant use of U.S. tax dollars—ideally, one would decide the former on the merits, not on a faulty understanding of the latter.

Second and relatedly, innumeracy can encourage cynical or unsavory people to try to profit—politically or financially (or both)—from Americans’ misunderstanding of basic, but important, statistics. Examples abound of politicians abusing numbers to achieve their desired talking points—the ones above are just some of the simplest—and, as we discussed in January, this unfortunate trend seems to be increasing as populism engulfs large chunks of both parties (and as voters increasingly want their priors confirmed, not pesky tradeoffs explained). There was a time, I think, that candidate Trump’s manifestly absurd promise to eliminate the debt in eight years would’ve been laughed off the Republican debate stage. Not anymore.

And, of course, social media today is overflowing with unprincipled grifters of all types seeking to use half-facts and scary numbers to prey on and profit from Americans’ pandemic insecurities. (Often those same folks are also stars in the MAGA-verse or the #Resistance—probably not a coincidence.) Depressingly, some journalists aren’t much better, though I tend to assume that their errors aren’t intentional and are instead a result of their own innumeracy (and the current media environment).

All of this misbehavior survives, if not thrives, because many of us either lack the basic math and reasoning skills to recognize and question the misinformation or we simply refuse to use them. None of that is good for the future of public policy and our lives, but there are some reasons for optimism on the horizon.

For one thing, math teachers are rethinking how to teach the subject to focus on foundational principles of comprehension and reasoning (instead of speed and memorization). As the New York Times explained earlier this year, moreover, data geeks have been trying to counter American innumeracy in adults by coming up with better ways to get the human brain to process numbers (like that data visualization video above) and by providing more information online. Think tanks (of course!) and other educational non-profits help too, as do some legacy and (ahem) startup media outlets and a growing body of individual “information entrepreneurs” (podcasts, newsletters, etc.). And, despite the problem signs, I do see a bustling private market—and thus some additional signs of hope—for combatting innumeracy and related misinformation, as well as a lot of the populist demagoguery that it often serves. Some people will surely be unreachable (always are), but better education and communication are critical, and there do appear to be a lot of people trying to do that.

Consumers, however, can help, too. For starters, we can be more discriminating viewers and distributors of content—especially when it confirms our priors just a little too perfectly. (Everyone fails at this occasionally, but the first step is admitting we have a problem.) Sometimes, simply reading through an article can often reveal that a scary/whatever headline stat isn’t nearly as scary/whatever as it first seemed, but other times you’ll need to find another source for complete context or additional data. That’s almost always just a short Google search away.

It’s similarly important to seek out and support subject matter experts who can be trusted to give the straight dope on the latest figure careening around the interwebs. With respect to COVID-19 vaccines in particular, FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver recently provided a great list of 13 things to consider when examining the latest efficacy numbers (there’s another tweet with more items):

I certainly don’t expect most normies to see a number and immediately recognize a base rate problem, Simpson’s Paradox, or other common mathematical error, but it’s quite easy these days to find someone who does. Yes, this means you might lose out on some of that sweet, dopamine-drenched social media engagement while you look for proper analysis, but it’s worth it in the long run—for you and your community.

And, hey, you might learn something along the way.

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.