Dear Capitolisters,

Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday of the year. It has the gluttony and sloth of Christmas, with little of the greed and envy. And it’s the only day of the year for which it’s socially acceptable to spend three days making a “side dish” that’s really your main course. Plus, of course, there’s family and football and parades and America(!) too. It’s great.

It’s also one of the few days where we Americans take a moment to be expressly thankful for what we have. I remember as a dumb teenager that this used to be my least favorite part of the day—having to go around the table saying what we’re thankful for (“so lame,” said Ungrateful Teen Scott)—but now it’s one of my favorites, especially these last two pandemic years. So, in keeping with this theme, today we’re going to spend some time being thankful for something often overlooked in today’s economic policy circles: our historically mind-blowing age of material abundance.

Now, amid incessant news of inflation and supply chains and other economic ripples, you may scoff at such “abundance” talk. But, in terms of basic necessities like food, clothing, and home goods, it’s really undeniable that Americans of all income levels are much wealthier today than we were only a few decades ago. And this improving quality of life, especially for lower- and middle-income workers, hasn’t been fueled by new debt but instead by a combination of higher incomes (which we discussed at length last year) and lower prices (thanks, global competition!). Thus, everyday essentials’ “time prices”—i.e., the number of hours you’d need to work to afford something—have steadily (though unevenly) declined over the longer term.

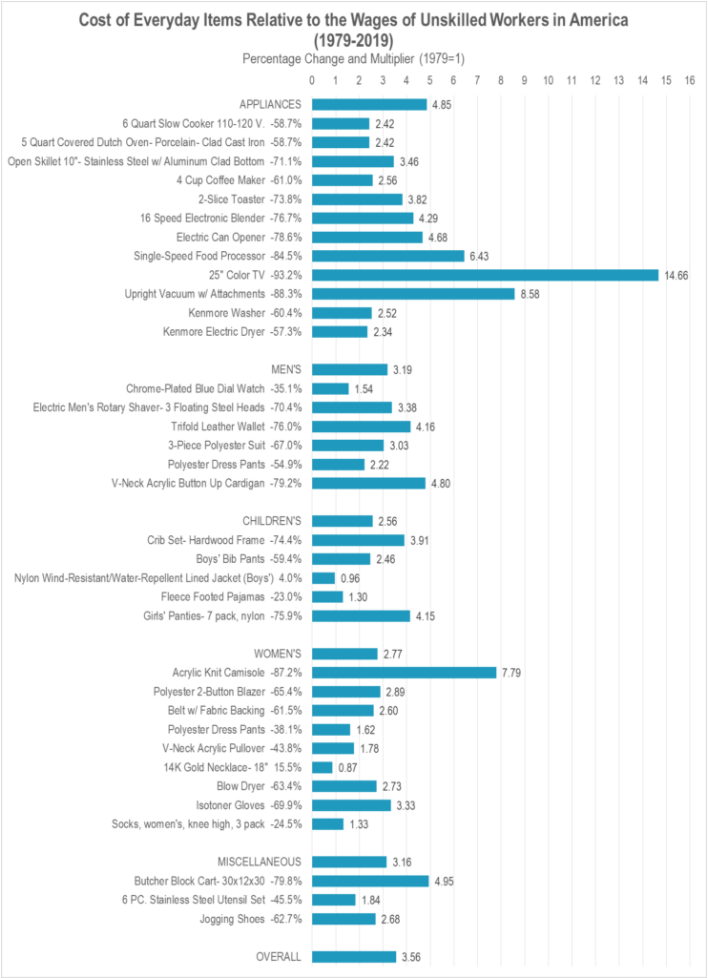

According to my Cato colleague Marian Tupy, for example, the average amount of time that an unskilled American worker had to work to earn enough money to buy a long list of everyday items has dropped by 72 percent since the late 1970s (when, by the way, U.S. manufacturing jobs were at their zenith). Put another way, for the same amount of work that allowed a blue collar American worker to purchase one item in 1979, he or she could buy 3.56 items in 2019 (on average).

Tupy (whose new book is a must-have for your optimistic coffee table) and his colleagues have found similarly impressive gains for American food consumption. Comparing the prices of 42 items (proteins, grains, vegetables, and fruits) from the early 1900s to the prices for the same items at Walmart today, and then factoring in changes in wages over the same period for workers at the bottom of the income ladder, they calculate that buying a basket of all of these food items would have required 47 hours of unskilled work back then but required only 10 hours of that same work in 2019—a 79 percent decline. “Put differently,” they say, “an unskilled laborer saw his or her purchasing power double every 34 years.” That’s undeniably great.

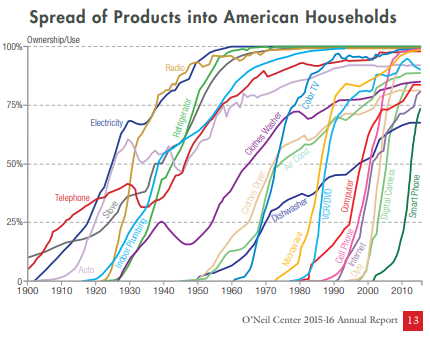

Americans’ increased long-term purchasing power has unsurprisingly translated to higher living standards. One of my favorite charts in this regard comes from a 2016 Southern Methodist University report showing the share of American households with access to telephones or cell phones, electricity, air conditioning, home appliances, TVs, computers, and other common household goods over time (data and sources are noted on Page 16 of the report, if you’re interested):

As you can see, by 2015 the vast majority of American households had these items, and many of these shares have increased even further since then. According to Pew, for example, now 97 percent of Americans have a cellphone (up from 91-92 percent in 2015), 85 percent have a smartphone (68-69 percent), and 53 percent have a tablet (45 percent), while 77 percent have home broadband (66-67 percent). The latest Census Bureau figures (for 2019) further show that more than 91 percent of households have AC, and about 85 percent have a washer/dryer. (By contrast, only about 5 percent of European households have AC—a share surely due in part to more temperate climates, but just as surely not all.)

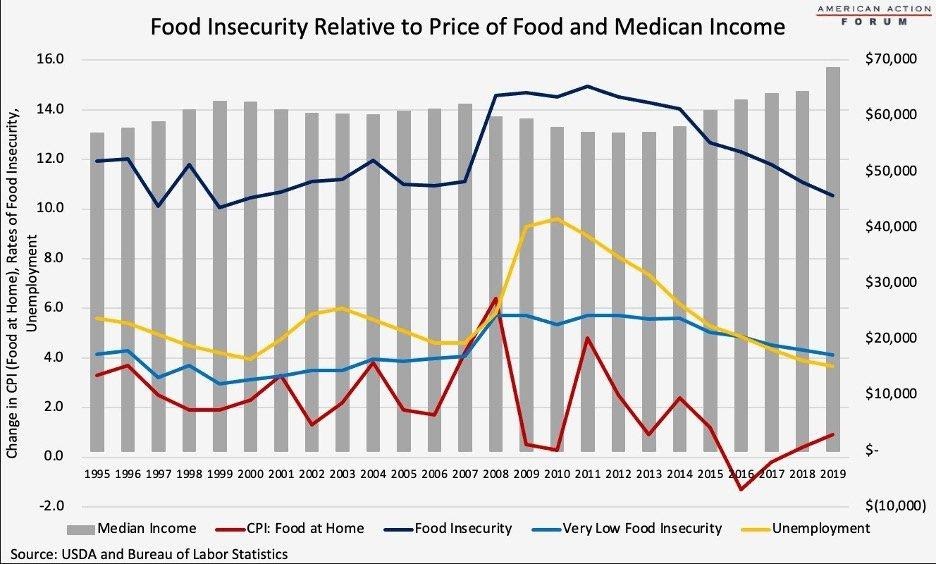

In terms of food consumption, we discussed earlier this year that Americans spent a historically low share of disposable income on food in 2019; “food insecurity,” meanwhile, reached an all-time low before the COVID-19 pandemic hit:

Even in a time of relatively high inflation and higher food prices, things are still better today than they were just a few years ago—and much better than they were decades before that.

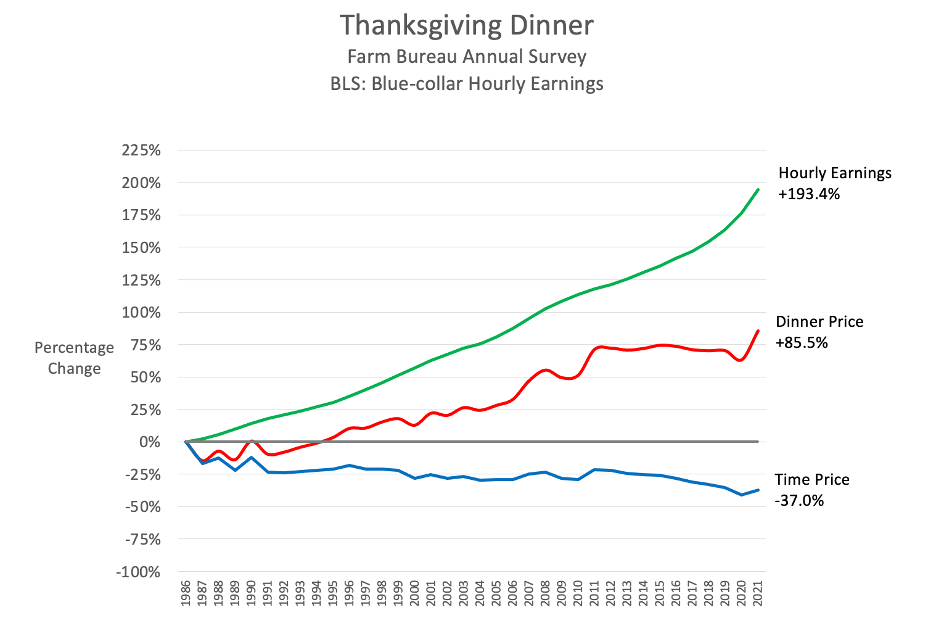

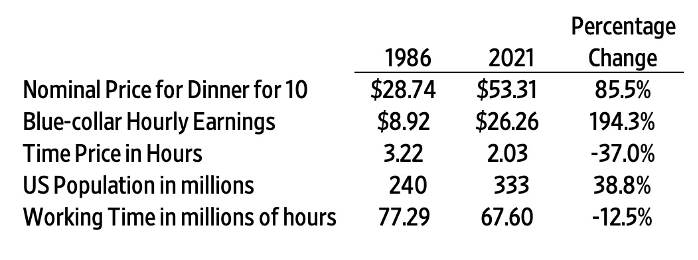

This includes Thanksgiving dinner, by the way. Responding to USDA figures showing a 14 percent increase in a traditional turkey dinner this year, Tupy last week recalculated the figures to account for blue-collar earnings and to show the longer-term trends:

Thus, that 14 percent price increase between 2020 and 2021 drops to 7 percent once you account for workers’ increased earnings. And, even more importantly, this year’s “time price” is actually a smidge lower than it was in 2019 (“the average American worker will work 3 minutes less in 2021 than he or she did in 2019 to pay for the meal”) and 37 percent lower than it was in the mid-1980s:

These analyses hit on two things that are often overlooked when we talk about prices and consumption: First, it’s essential to consider not only the nominal (sticker) price of something but also the incomes that pay for it. If the nominal price of a widget remains flat, but you earn just a little bit more each year, then that widget has, for you at least, actually gotten a little cheaper. The second big thing is time (wow, deep): While short-term price (or, as we’ve discussed, income) changes tend to get all of the media and policy attention, they often miss—unintentionally, one hopes—the real story of long-term, generational progress across a wide range of consumption metrics.

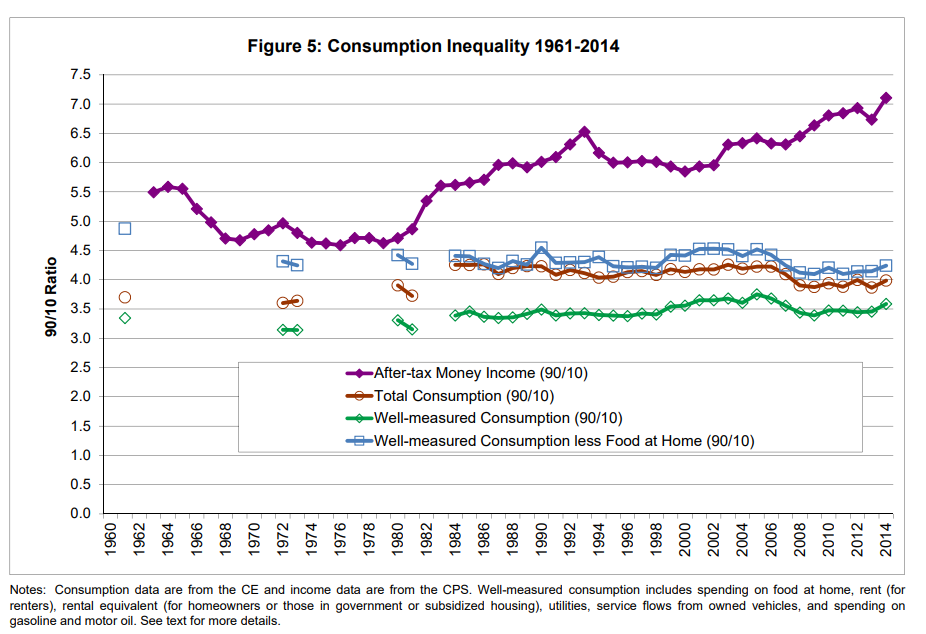

Gains in Americans’ purchasing power and material well-being are often pooh-poohed by pessimistic folks in Washington, but they do matter—and far beyond just having another cheap T-shirt or a sweet 4K TV. For example, research from economist Bruce Sacrecdote finds that the consumption gains for below-median income families over the last six decades have been incredibly impressive, even as income inequality has increased over the same period. In particular, he finds that American households with lower incomes not only have more cars and bigger houses than their earlier-era counterparts, but that their overall consumption (adjusted for inflation) increased between 62 percent and 164 percent between 1960 to 2015, not fully accounting for improvements in quality (which for some items, such as cars and homes, have also been substantial). In other words, poorer Americans today can consume about twice as many goods and services as did their 1960s counterparts.

Accounting for consumption improvements also dramatically narrows inequality, especially for single parents. As shown in the chart below, the rise in income inequality as measured by the “90/10 ratio” (wealthy 90th percentile Americans versus poor 10th percentile) far exceeded the 90/10 ratio change in consumption inequality (which was actually down in recent years). So while wealthy Americans’ incomes may have outpaced those of poor Americans in recent decades, there’s been little to no change—and maybe even a little improvement—in terms of what we actually consume (which is, you know, kinda the main point of those incomes).

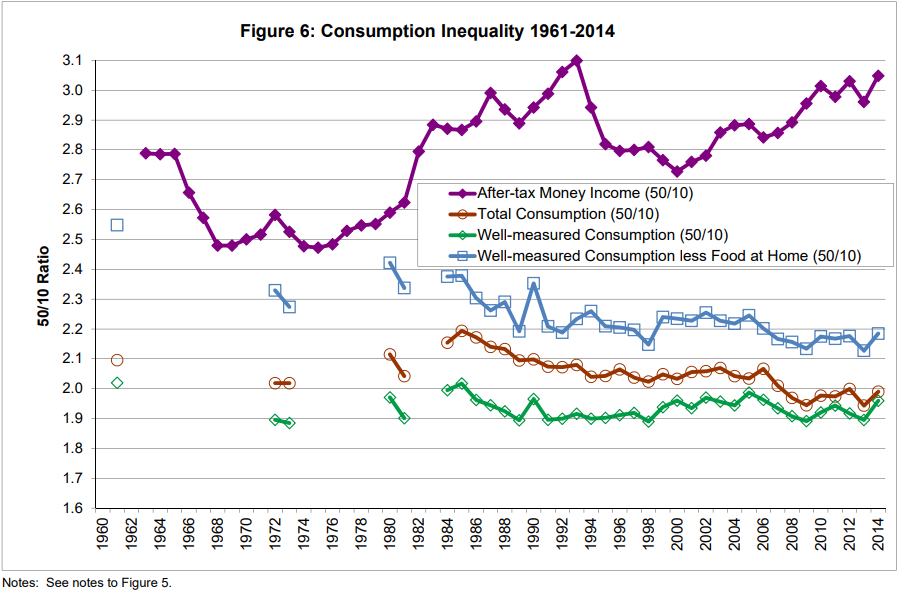

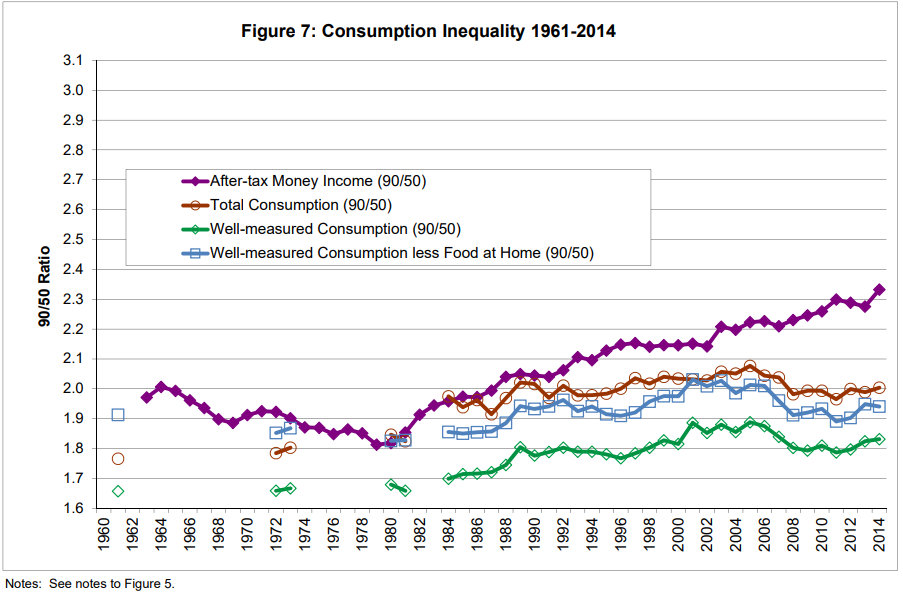

Similar divergence appears when you compare the middle class to the poor (50/10) or the wealthy to the middle class (90/50):

In fact, the middle class 50th percentile has made clear consumption gains on the rich 90th percentile.

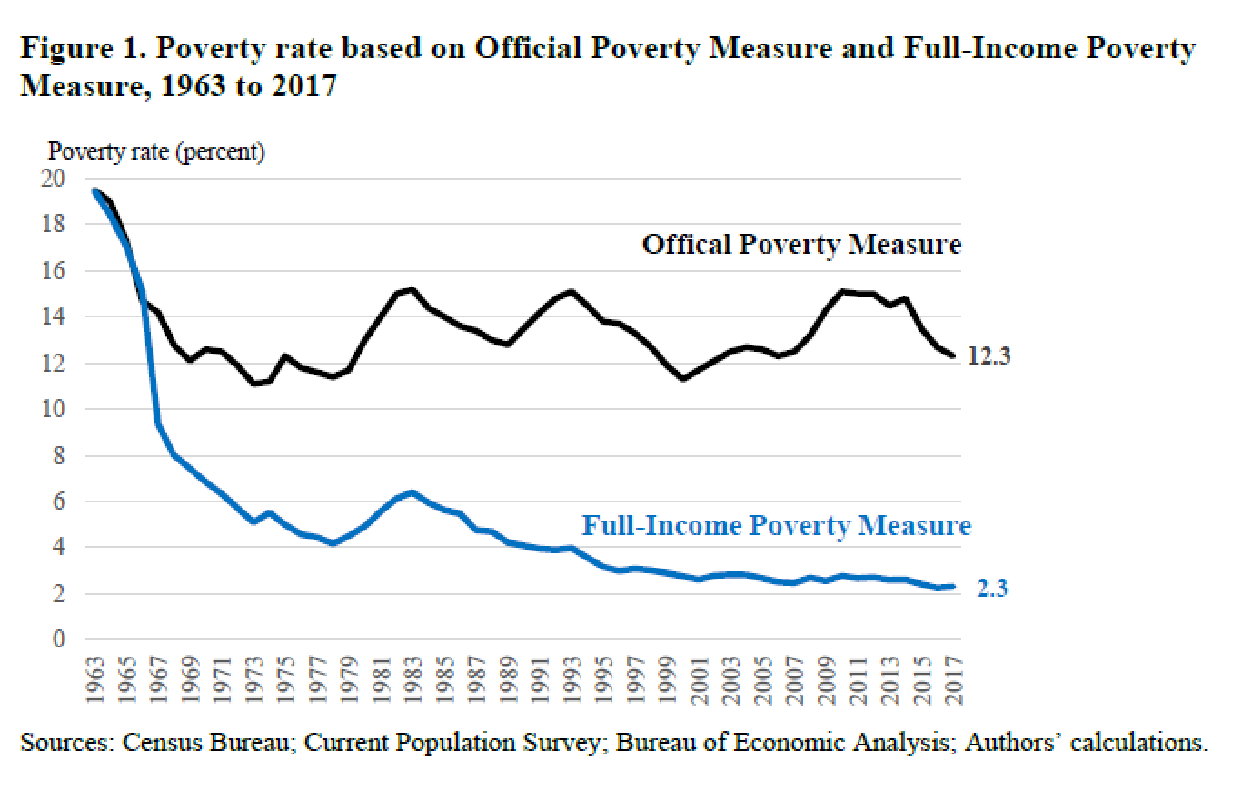

U.S. government definitions of poverty also consider both income and consumption needs (the “poverty threshold”), and both the standard and supplemental poverty rates hit all-time lows in 2019 before the pandemic hit. The news is even better when you recalculate, as one recent paper did, the figures using the same government poverty standard as established in 1963 but more comprehensive and accurate measures of household income and inflation:

Of course, getting even this small share of our fellow Americans out of poverty is a worthwhile goal, and surely some consumption challenges remain—particularly in health care, higher education, and certain housing markets. However, we have more money to spend on these services because of declining time-prices elsewhere, and these sectors are captured in the standard inflation metrics that have been outpaced by middle class wages over the last few decades. (More on these points here, if you’re interested.) Some of these sectors, moreover, are regionally concentrated or might be primarily a result of higher productivity elsewhere in the economy (aka the “Baumol effect”—but we’ll cover that in another newsletter). And, of course, each of these sectors is already highly subsidized, protected, and regulated too.

Regardless, the general American consumption story over the last few decades is undeniably great. Most Americans today enjoy living standards that were reserved for billionaires a century ago and well above those of their 1960s counterparts. Isolated swoons and challenges aside, the general direction of America’s great prosperity machine is positive. And for that, we should be thankful.

Now pass the stuffing.

(Capitolism will be off next week. Happy Thanksgiving!)

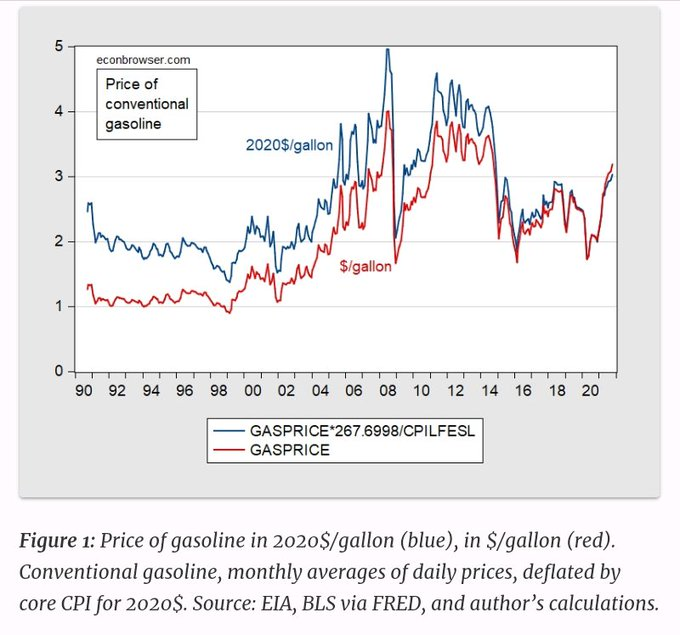

Chart of the Week

Apparently this is a national emergency (more):

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.