Easily one of the worst and most cynical plays in modern politics is the practice of “nutpicking.” Partisans will treat the loopy utterance of some random member of the other team as broadly representative of the entire movement, thereby seeking to discredit it (and its saner and stronger players) and to reassure their comrades that everyone on the other side is a whackadoodle freak not worth engaging. The practice of nutpicking is widespread on both sides of the aisle, especially on social media, and typically related to culture war issues—family, race, gender, crime, etc.—that arouse strong feelings and push people’s buttons.

Lately, however, the nutpickers have found their way into the tariff debate, as fans of the president’s trade policies—including the vice president himself—have seized on a few recent events to declare victory over all “the economists” who, blinded by ideology and ivory tower groupthink, confidently predicted this spring that the tariffs would usher in economic doom for the country. The victory dance, however, is proving not just cynical and myopic but alarmingly premature.

Granted, some people did make dire predictions after multiple Trump tariff announcements caused stock markets to crater and recession fears to mount. A few of them even had “Ph.D.” attached to their names. But, in classic nutpicker fashion, these folks were most definitely not indicative of the economics profession (or U.S. trade watchers) more broadly. They (we) certainly didn’t get everything right in the run-up to our current, still-unfolding Trump Tariffpalooza, and were certainly critical—highly critical—of the policies. In general, however, economists’ warnings were focused not on another Great Depression (or whatever) but the real and tangible damage that President Donald Trump’s tariffs could inflict on the economy.

And, quite frankly, the latest economic data are proving “the economists” right.

As a non-paying reader, you are receiving a truncated version of Capitolism. You can read Scott’s full newsletter by becoming a member here.

The Misses

Let’s start with the two things economists and other experts, myself included, actually did miss—at least partially and so far. First, foreign companies appear to have shouldered some of the tariff burden by lowering their sales prices to offset U.S. importers’ new tariff costs—more so than they did during Trump’s first term, when American companies and consumers paid almost all of the taxes (and paid higher U.S. prices, too). In reality, however, this isn’t much of a dunk: As we discussed last September, economists have always said that foreigners could indirectly pay some or all of a tariff’s cost, and how this “shakes out in the real world will depend on lots of things.”

Even more important is that—even this time around—the best available evidence indicates that foreigners are so far absorbing a small fraction of the total tariff burden. The latest figures from Goldman Sachs, for example, put the figure at just 14 percent, while new U.S. import price data, which omit tariffs, show negligible—if any—price cuts by foreign exporters. Crowing that Americans are paying at least 86 percent of the tariffs—versus 95-plus percent last time around—isn’t a real win for Team Tariff.

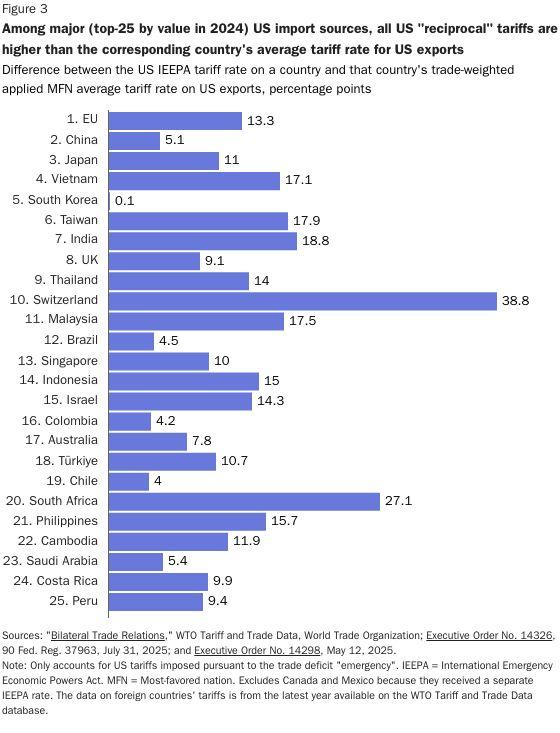

The arguably bigger expert miss is the extent of foreign government retaliation. As we’ve discussed, both politics and strategy motivate governments to retaliate against unilateral tariffs with tariffs (or other protectionism) of their own. This very thing happened during Trump’s first-term tariffs, with several governments—but certainly not all—swiftly imposing new restrictions on U.S. exports and imposing additional harm to the economy (especially farmers). This time, however, the retaliation has been limited to China and—to a much lesser extent—Canada, while other major players like the European Union and Mexico have held off.

But this, too, isn’t an “economist” kill-shot. Beyond the fact that there has been significant retaliation against more than $100 billion in American exports (with attendant harms to the U.S. farm economy), economists’ primary disdain for tariffs focuses inward—not outward. Their concerns, in particular, emphasize how tariffs distort domestic prices, consumption, investment, and output, discourage protected American firms from innovating, fuel U.S. economic uncertainty and political dysfunction, and impose other various harms on the United States—with retaliation only one of many factors in the last bucket. Economists’ tariff forecasts, such as those from the Tax Foundation and Yale Budget Lab, thus offer retaliation-free versions of their analyses—versions that still show significant harms to the U.S. economy even if nobody retaliates.

Finally, it’s important to note that more retaliation could eventually materialize, for example, if trade deals collapse or different foreign leaders are elected. (And, as we’ll discuss in a future column, foreign individuals are retaliating too.) For now, however, most countries are doing the economically smart thing by avoiding self-immolation and possible escalation and by trading more with one another to offset the damage from U.S. tariffs. And, yes, that’s a bit of a surprise—one most economists welcome.

The Hits

Meanwhile, the harms those wonky models foresaw are, in fact, starting to materialize after the lags we previously detailed. As I was preparing to write this column, Harvard economist Jason Furman swooped in and stole my thunder (ha) in a great New York Times piece on this very subject. I’ll do the efficient thing and piggyback off his response to those who have boldly denounced “the economists” this summer.

Furman makes several important points that many folks—including yours truly—have been making since the beginning of Trump’s second term (if not even earlier). First and most basically, economists always saw a full-on, tariff-induced recession in the United States as a long shot:

[I]mported goods account for only 11 percent of the U.S. G.D.P. Most of the economy is made up of sectors like health, education and other services that are not hugely affected by tariffs. In addition, the U.S. economy has extraordinary strength and momentum, which gave us some of the highest growth rates of any advanced economy both before Covid (in Mr. Trump’s first term) and after the start of the pandemic (during Joe Biden’s term). The artificial intelligence boom, including data center construction, is helping, too.

Thus, as Capitolism discussed back in November, even much bigger and broader tariffs—and widespread retaliation—in 2025 wouldn’t “guarantee a recession.” As I told podcaster Matt Lewis during even the peak of April’s “Liberation Day” chaos, moreover, tariff critics should be careful about “hysterical responses” to Trump’s trade policies because the “U.S. economy is massive and dynamic and mainly services,” so tariffs can do lots of damage without “imploding” it or the global economy. And, I presciently added, tariff fans will seize on critics being wildly wrong about this stuff, thus making future advocacy more difficult. (Nailed it.)

Second, Furman notes, Trump has repeatedly announced high and broad tariffs with no exceptions, only to then reduce their size and scope—often in response to market (and economist!) worries. The “most consequential” of these tariff amendments, in Jason’s eyes, was Trump’s decision to reduce the 145 percent tariff blockade on all Chinese imports to an average rate of around 55 percent—still high but not an effective ban (especially with many Chinese products enjoying much lower or even zero tariffs). Trump also temporarily paused his “Liberation Day” tariffs and—even now that they’re back—has assigned lower tariffs for most of the countries involved while exempting consumer electronics, pharmaceuticals, and several other big-ticket items (for the time being). Just as importantly, Trump’s “fentanyl” tariffs don’t apply to a large portion of Canadian and Mexican goods because he subsequently exempted products that qualify under the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Other tariffs, such as those for automotive goods, also have carve-outs that were added after the original announcement.

These exemptions and—as we’ve discussed—moves by U.S. companies to avoid the highest tariffs (e.g., importing before tariffs hit, shifting supply chains to lower-tariff countries, reclassifying products, etc.) have had a significant effect on the tariffs’ near-term economic effects. In fact, Barclays economists estimate that more than half (52 percent) of all imports entered the United States duty-free in June 2025, and the effective tariff rate averaged just 9 percent—still historically high but about half what you’d get from a static calculation based on Trump’s initial tariff announcements (before exemptions and delays).

These tariffs can still cause problems, of course, but they’re a far cry from what Trump originally promised—and what elicited such a strong initial reaction from financial markets and many economists.

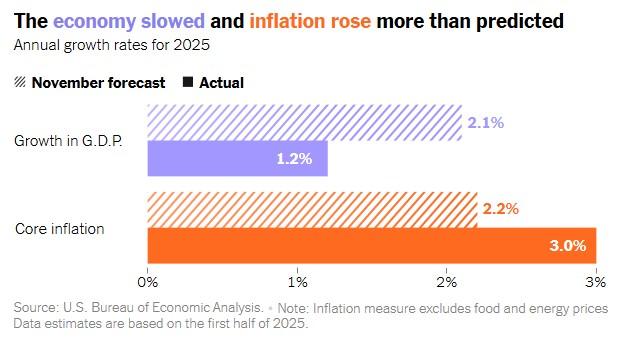

Finally, Furman notes, there are signs that tariffs are hitting the U.S. economy—just as economists warned, and even though the latest data are from July (when many of the tariffs hadn’t fully landed). He shows, for example, that the first half of 2025 saw significantly slower growth and higher prices than what was expected late last year, with prices of import-heavy goods—toys, computers, appliances, etc.—being particularly frothy.

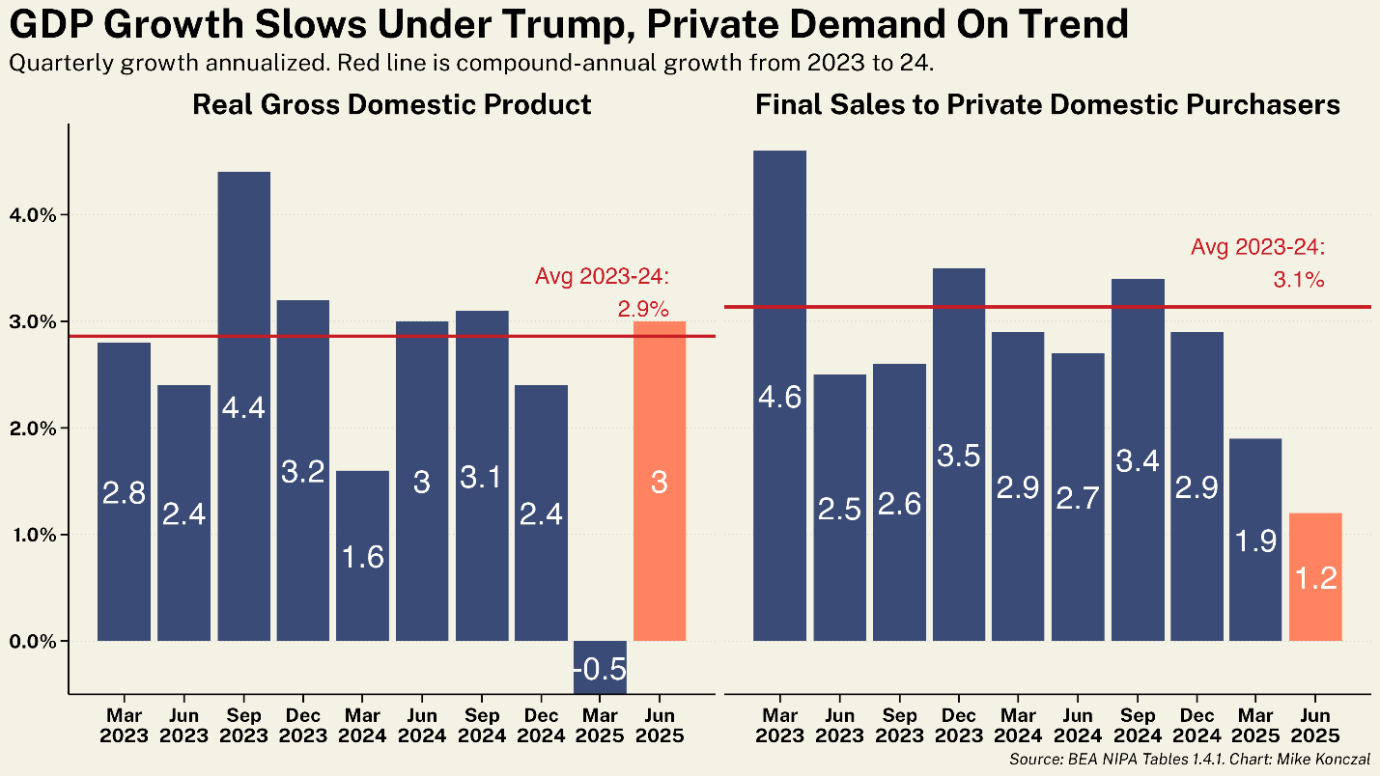

The 2025 growth deceleration is even more pronounced when you strip out the trade and inventory figures that the tariffs distorted because importers stocked up in advance:

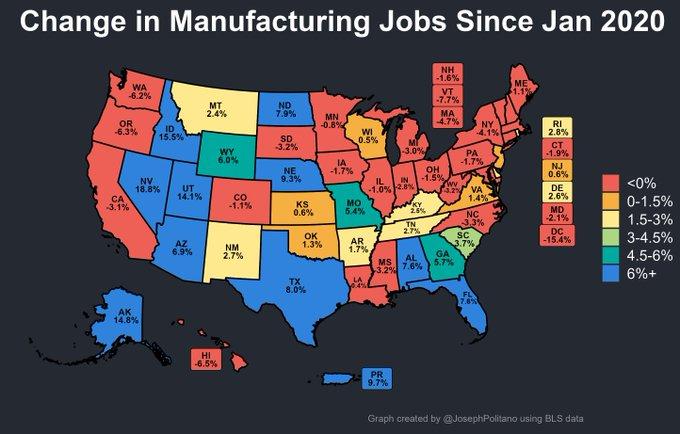

Subsequent data have reinforced economists’ (non-hysterical) concerns about the tariffs and related policy uncertainty. The day after Furman published his piece, for example, federal data showed a substantial deceleration in U.S. jobs growth in July and downward revisions for June and May that were so rough they unfortunately cost the Bureau of Labor Statistics commissioner her job. (Since April’s “Liberation Day,” in fact, the U.S. has lost 37,000 manufacturing jobs—precisely the opposite of what tariff champions want.)

Last week’s consumer price data, meanwhile, showed more increases in July for goods that are primarily imported. Two days after that, July producer prices—which don’t directly reflect tariffs but instead show how U.S. companies price their goods and services—increased at their fastest rate since 2022, indicating that U.S. companies weren’t fully absorbing the tariffs they’ve been paying or are raising their own prices (and that consumers would see more price gains in the months ahead). In a good and data-rich piece, economist John Mauldin summarizes the situation well:

Rising goods inflation isn’t an unintended side effect of tariff policies. It is one of the goals. Higher prices for imported goods are supposed to incentivize more domestic production, create more manufacturing jobs, and make the US less reliant on imports. That’s the theory, at least. Whether it will have those effects is another subject. But the higher-prices part is here, and it’s becoming evident in the inflation data.

Speaking of companies absorbing tariffs, recent weeks have also featured second-quarter earnings reports showing U.S. companies—especially manufacturers—shelling out billions of dollars in additional tariff costs since January. How that leaks into future growth and price data—and how it interacts with U.S. central bank policy—will be one of the biggest economic stories of the second half.

Not much of an economist “miss,” is it?

Overall, though, the reality is that, as Furman said, “it is still early days”—especially with our backward-looking data. More tariffs have come online in July and August—meaning rates are higher than what Barclays estimated above—and more are expected in the weeks ahead, as current loopholes (like this one that allows small-dollar, direct-to-consumer sales) close and sectoral investigations are completed or expanded. Importing U.S. companies, meanwhile, are running low on tariff-free inventories or, now that the global tariffs are basically set, have decided they won’t (or can’t) keep absorbing tariff costs. As these and other costs trickle through the economy in the months ahead—and as still-elevated uncertainty persists—we should expect more pain in forthcoming U.S. price, jobs, and GDP data. (But, again, probably not a recession without other forces adding to the headwinds and/or an unlikely, worst-case “contagion” freakout by financial markets like we saw in April.)

Why the Nutpicking?

As noted at the outset, nutpicking is certainly nothing new in U.S. politics, and it’s easy to see why tariff advocates like it today. Using cherry-picked data and soundbites to discredit all “economists” plays into longstanding—and sometimes probably deserved—biases against the “expert class.” It primes followers to ignore future information and warnings from reputable, independent wonks (on tariffs and anything else) and instead get their news and analysis from only certified in-group sources—information that’s sure to parrot the company line and soothingly confirm pre-existing biases. And it importantly shifts the standard for successful economic policy from actually achieving important stated objectives (jobs, output, geopolitics, etc.) to simply avoiding the beyond-worst-case outcome that uninformed online commentators and a few rogue “experts” once hysterically predicted. Never mind, of course, that “didn’t collapse the economy or cause skyrocketing inflation” is about the lowest bar ever for any public policy, trade or otherwise. When that becomes the new litmus test, all the costs and inefficacy can more easily be ignored.

And, let’s face it, the last few months have indeed seen more than a few pundits, politicians, and partisans—and even a few “economists”—hyperventilating on TV about Trump’s tariffs ushering in the next Great Depression or something. Overall, however, the portrayal of economists and trade wonks as blinkered “fundamentalist” ideologues who totally botched our current economic reality is laughably out of touch. For starters, economists’ work on things like “strategic” trade policy and “optimal tariffs” (see here and here for brand new papers along these lines) shows that they’re not uniformly anti-tariff, at least in theory, and that many find that tariffs can “work” under certain idealized conditions. Their criticisms become louder and more uniform, however, when the subject turns to implementing such tariffs in practice, because both history and empirical research reveal myriad practical and political hurdles to an ideal tariff regime that, along with the potential for foreign retaliation, make free trade the better long-term policy choice in most situations. (Always remember: The protectionists are the real fundamentalists.)

Furthermore, most serious economists and trade experts have played the Trump 2.0 era pretty straight, repeatedly warning of potential harms—higher prices, slower growth, uncertainty, cronyism, etc.—that are, in fact, now materializing. They’ve also generally avoided over-the-top claims that the tariffs alone will cause some kind of economic Armageddon, though that doesn’t make them good policy in their own right. As Furman notes, for example, tariffs shaving just half of a percentage point off U.S. GDP means about $150 billion in needless economic losses—“the equivalent of every household in America taking around $1,000 and lighting it on fire — then doing it again every year. Forever.” Or, as I put it to Lewis back in April: I could cut off my own foot without dying, but it doesn’t mean cutting off my foot is a good idea.

And that, in a nutshell, increasingly appears to be the current U.S. tariff situation—just as the economists predicted.

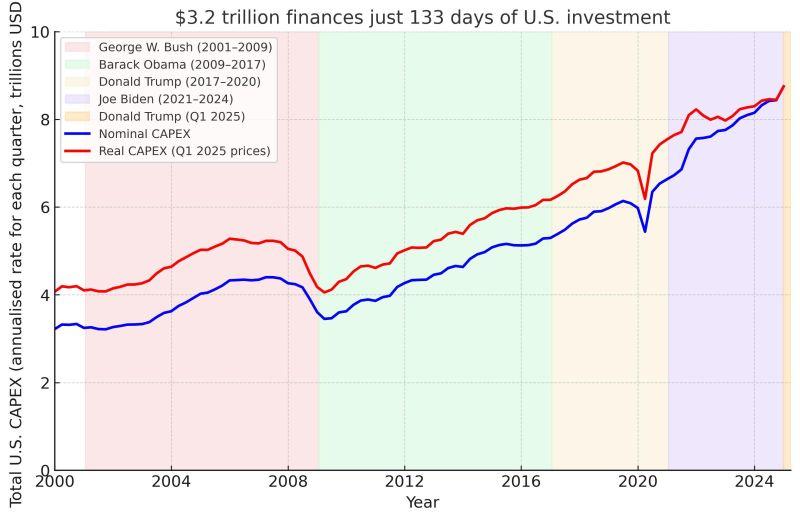

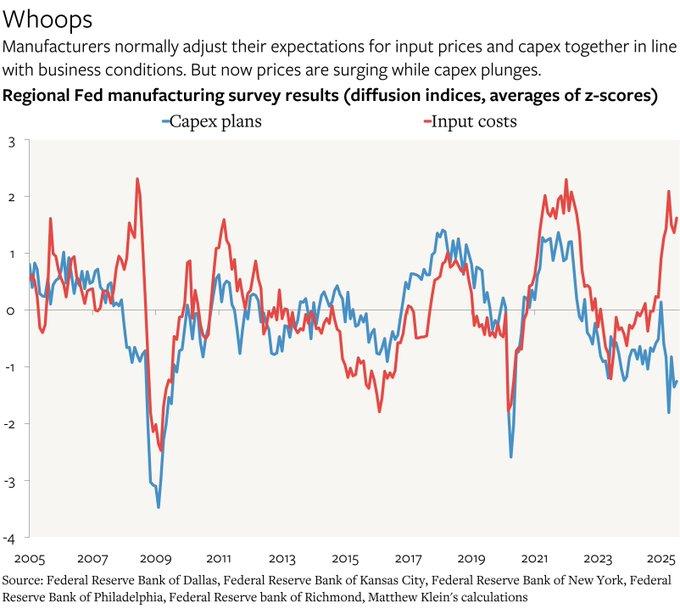

Chart(s) of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.