Dear Capitolisters,

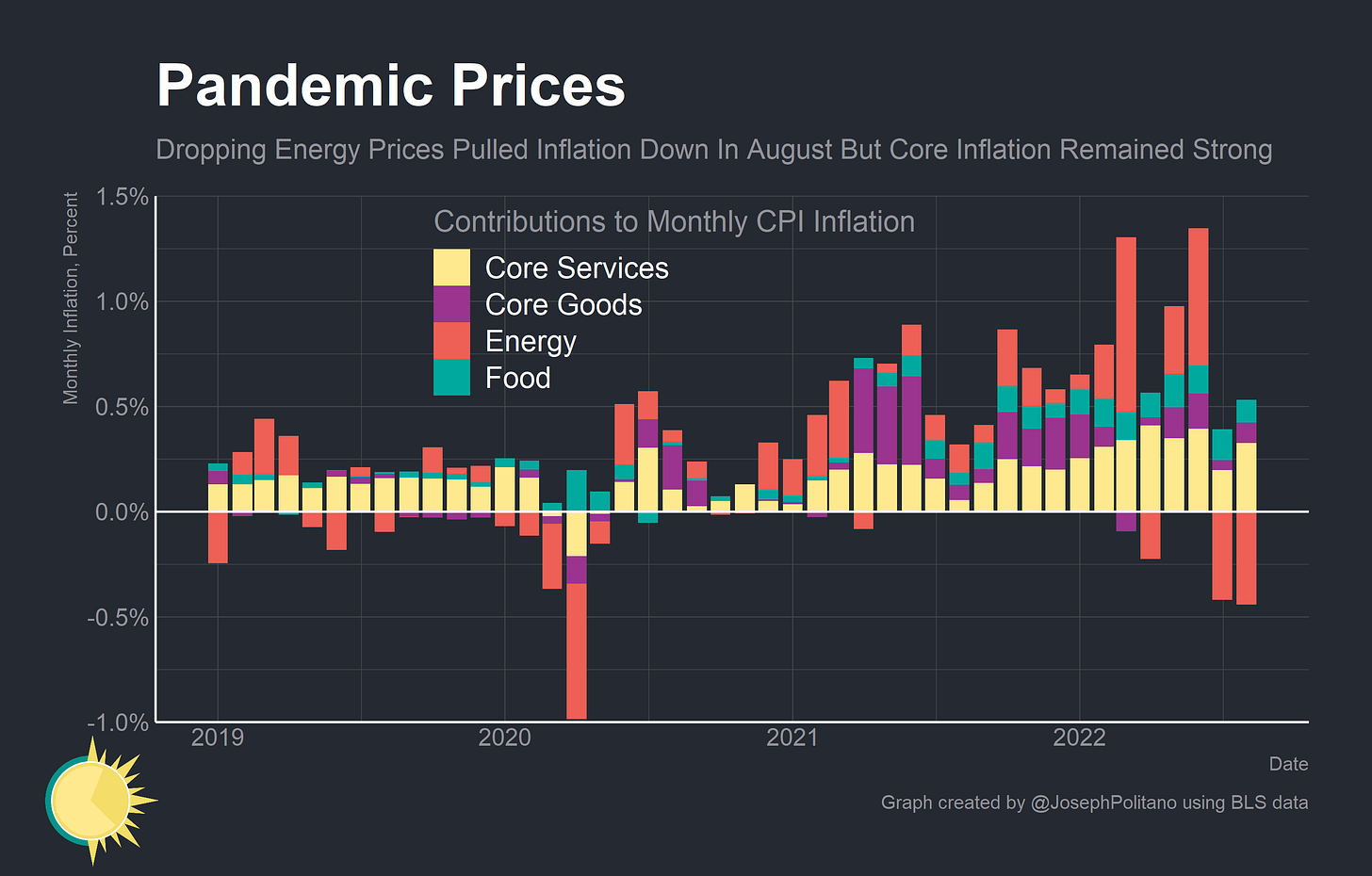

In case you missed it, last week’s inflation numbers were … not great. The consumer price index for August came in well above expectations, driven in large part by higher food prices and rents (a big part of “core services” below) that more than offset a welcome decline in energy prices.

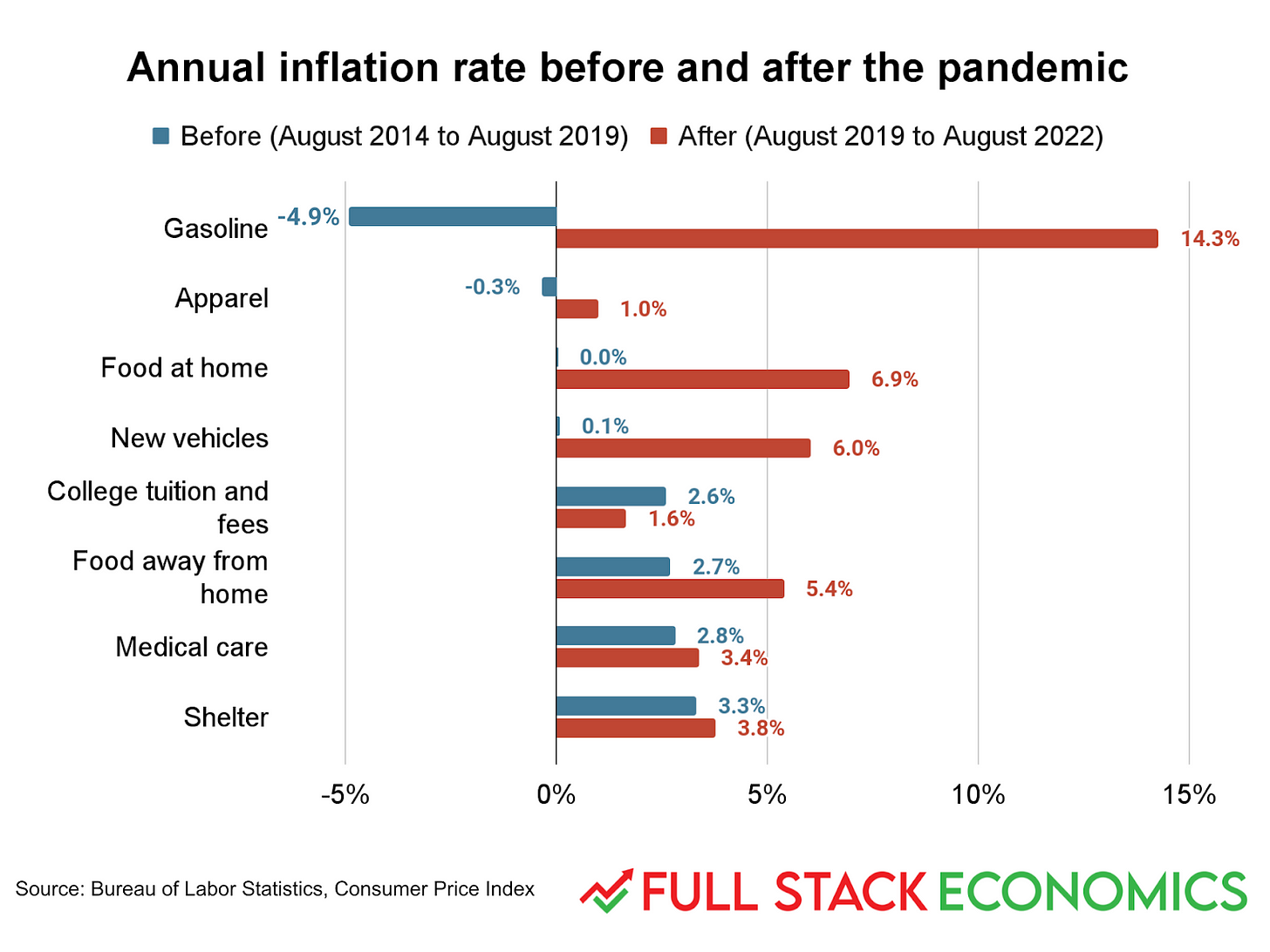

From the experts I read (including in the first link above), the CPI print wasn’t all bad and might even have some good news buried therein. But that’s certainly not the case for food and housing, both of which will—for various reasons (e.g., Ukraine, U.S. droughts, housing supply and demand issues, and some wonky calculation issues)—probably continue to remain elevated in forthcoming CPI reports until at least next year.

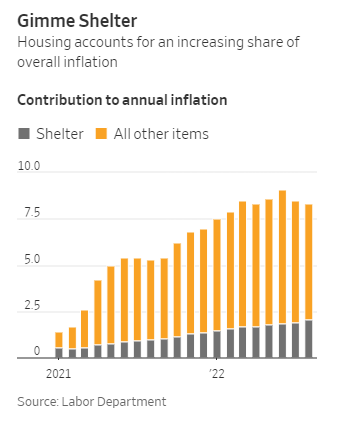

These data aren’t merely a headache for the inflation-obsessed Federal Reserve (shelter inflation is about 40 percent of total CPI), but also—of course—a real problem for everyday Americans. We all need food and housing, and higher spending on these necessities can diminish spending elsewhere. And, while we may be accustomed to ever-higher housing prices (sigh), the regular shock of food prices doing not just the same but way worse—something Americans haven’t experienced in ages—can inflict a disproportionately large psychological toll on consumers, causing us to pull back even more. None of this is good for the U.S. economy.

As noted, there are some signs that prices will get tamer next year. But right now, you’d think that persistent food and housing price pressures would push American policymakers to be laser focused on keeping food and housing costs down—or, at least, not actively working to increase them.

Think again.

Cheering Higher Food and Housing Prices?

Let’s start with food. Last week, more than a dozen Florida legislators, including Sens. Marco Rubio and Rick Scott, filed a petition with the United States trade representative asking that it investigate fresh fruit and vegetable imports from Mexico and provide “relief” for Florida growers under “Section 301” of the Trade Act of 1974. The lawmakers claim that government programs and low labor wage rates have caused Mexican sales of “unfairly priced” (read: inexpensive) cucumbers, bell peppers, squash, strawberries, and blueberries to surge in recent years, harming Florida farmers. The congressional delegation thus asked USTR “to secure the relief needed to sustain the Florida seasonal and perishable agricultural industry.”

While the lawmakers don’t say what kind of “relief” they want, it’s clear from the petition that their ultimate goal here is a restriction on Mexican imports and, by extension, higher food prices in the U.S. market. Reason’s Eric Boehm speculates that “Rubio and his colleagues are seeking tariffs on Mexican produce” because “Section 301 is the same mechanism the Trump administration used to impose wide-ranging tariffs on goods imported from China.” That’s true and the obvious play, but, given how broad the law is (see my recent Cato paper on 301 for more), the remedy could be some other mechanism, such as quotas or price floors, which the U.S. government has previously negotiated with Mexico for tomatoes and sugar (of course, sugar). Regardless, if you’re using trade measures to remedy a “surge” in “unfairly priced” produce, the solution will involve boosting domestic market prices (to make the U.S. industry “competitive” again). That’s the whole point.

Now, leaving aside the fact that low wages in a developing country aren’t “unfair trade,” that the United States has its own trade barriers (ahem, sugar) and has provided billions in subsidies to Florida farmers over the years, that many other U.S. states produce these items and aren’t complaining to the feds, and that the issue of seasonal Mexican produce has been repeatedly debated—and Florida lawmakers’ requests for protection repeatedly rejected—for decades, here we have a group of American politicians urging new taxes on healthy fruits and vegetables, right in the middle of some of the highest U.S. food inflation in decades. And these Florida lawmakers are not only doing so, but they’re actually issuing press releases to show off their efforts. Crazy stuff.

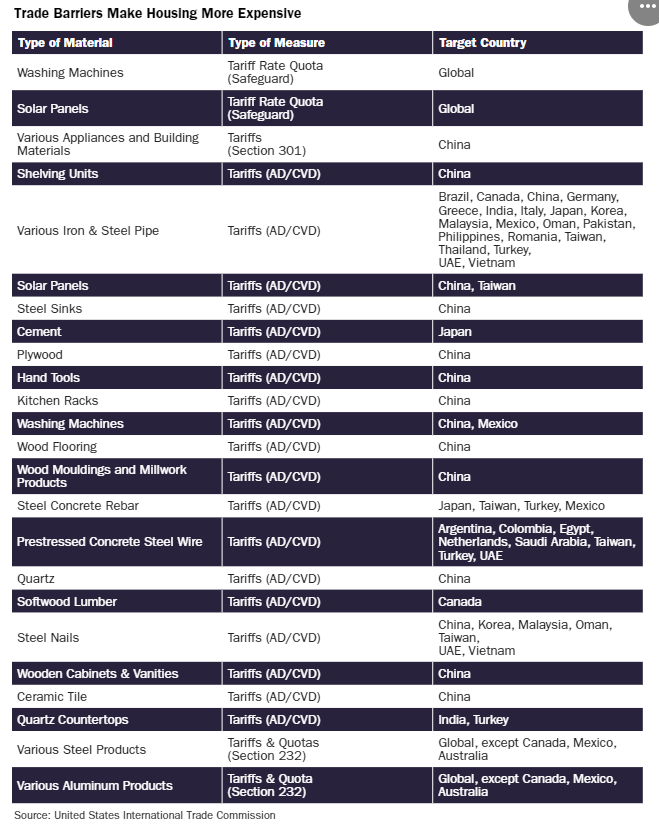

Things are arguably nuttier in housing. In particular, the Commerce Department recently announced preliminary anti-dumping duties of 323.12 percent on Indian quartz countertops, which are quite popular these days in home construction. As we’ve discussed, the U.S. anti-dumping game is rigged against importers and consumers, so duties are annoying but not exactly surprising. But this case, as NDP Analytics’ Dan Ikenson explained last week, marks a new low. In particular, one of the exporters’ lawyers missed an unusual filing deadline by a whole five hours, so Commerce disregarded everything that the company had submitted to calculate “dumping” and instead applied a punitive (“Adverse Facts Available” or “AFA”) duty rate supposedly reserved for “uncooperative” companies. Based on this rate and a 0.0 percent rate (i.e., no dumping) calculated for the other exporter under investigation, Commerce applied a 161.56 percent duty rate to 51 other Indian exporters, who of course had nothing to do with the filing mistake. And, because the Commerce Department calculates anti-dumping duties retrospectively and U.S. importers pay these duties, the government could cripple dozens of American companies—wholesalers, retailers, construction companies, etc.—who imported Indian quartz years ago:

But the most significant collateral damage will be borne by U.S. importers, who are now on the hook for a duty (tax) bill of more than $300 million. There is no way this enormous sum can be recovered by these companies, as the imported countertops were sold years ago and are now installed in homes, hotels, and offices throughout the United States. Many of the smaller companies will declare bankruptcy, as they find themselves unable to absorb these unexpected, massive costs.

Not only are we taxing and maybe even bankrupting U.S. construction companies during a national housing shortage, but the new, insanely high duties will also serve as the estimated rate for future imports. Thus, as Ikenson notes, “Americans should expect large price increases going forward” because “India accounts for about one fourth of all imports of these products by volume.” (And if demand shifts to other types of countertops, we’d probably see higher prices there too.)

These are preliminary rates, so there’s a chance that Commerce comes to its senses this fall. But there’s little reason to assume it will because AFA rates have become increasingly common in U.S. anti-dumping cases and U.S. law forbids agencies from considering duties’ harms to consumers, importers, or the broader U.S. economy. This is how, as I wrote last year, we end up with the United States applying anti-dumping duties to numerous types of construction materials—duties that, as one recent economic analysis demonstrated—increase U.S. prices.

Determining how these taxes affect the final prices of housing—for new homes or rents—is a difficult, market-specific undertaking. But, as the aforementioned economists note, “U.S. homebuilders report that they often pass on higher material costs to homebuyers, and previous research notes that many homes in the United States are priced close to their construction cost, of which materials (e.g., lumber) are a significant part.” And this is all happening during a crippling bout of housing inflation.

The U.S. trade remedies system simply doesn’t care – just as Congress intended.

Why? Public Choice 101.

That U.S. policymakers would work to increase some prices of inflation-racked necessities isn’t exactly breaking news—it’s something we’ve discussed here repeatedly over the last couple years. Yet the quartz and produce examples really demonstrate just how crazy things can get in this regard—politicians begging for higher food prices and the Commerce Department punishing struggling U.S. homebuilders, right as food and housing prices weigh on the economy and the national psyche. As crazy as it is, however, it’s also right in line with what public choice theory predicts. For those who don’t recall, we covered public choice in depth when examining the long and sordid history of U.S. industrial policy. For that produce petition, we have a classic “collective action” problem:

[E]lected officials frequently advance … policies that confer concentrated benefits upon small, homogenous, often local interest groups and impose diffuse (but larger) costs upon the general public, because only the small groups have sufficient motivation to follow the issues closely and apply political pressure (lobbying, campaign contributions, and votes) based thereon. Because the public is “rationally ignorant” about these policies (and thus does not tie their votes or contributions to them), elected officials act rationally in supporting them, even when the policies are known to produce net losses for the country.

In the current case, Florida lawmakers are counting on the rapt attention of the local farmers who stand to benefit handsomely from any new import protection and who just so happen to be heading to the polls in a few weeks. The pols can promote their efforts on the campaign trail, and the farmers will sit and nod like they always do.

The officials are also counting on the near-total inattention of the rest of the U.S. public, which has better things to do than patrol the internet for boring, legalistic proposals that would add a few bucks to their weekly grocery bills. Throw in the usual foreign-versus-American framing and general media disinterest in boring economic policy issues, and this petition is a safe and easy play—even if it might bolster a bad law and eventually end up hurting American consumers. Judging from the press coverage of the new proposal, the politicians are totally right.

In the quartz case, meanwhile, we see again how implementation of U.S. policy so often becomes infected by politics and disconnected from economic reality—again just as public choice predicts:

Research shows, for example, that government agencies’ agendas often mirror those of the members of the congressional committees that primarily oversee them—members that often actively seek out these committee assignments in order to affect the regulatory agencies beneath them. Thus, the same political pressures that distort elected officials’ creation of and support for a certain industrial policy can similarly distort the federal bureaucracy’s work to effectuate it. Similarly, numerous studies show that agencies can become “captured” by motivated special interest groups (or their elected benefactors) who use the agency to further their own narrow interests at the broader public’s expense. Even where political pressure is limited (often by design), capture can occur where bureaucrats lack the same level of specialized knowledge as the entities they’re regulating and thus grow to rely on those entities for both information and manpower (aka “the revolving door”).

As we’ve discussed, decades of amendments to the U.S. anti-dumping law have made it increasingly protectionist and disconnected from any plausible definition of “dumping” or predatory pricing. Commerce, meanwhile, has long been captured by a small handful of domestic producers (and their lawyers) and proven more than willing to abuse the ample discretion Congress has given it to deliver massive, ahem, rents to those same producers. Rational ignorance, moreover, again ensures that normies have no idea what’s going on—a cluelessness exacerbated by the law’s mind-numbing complexity (which is no doubt intentional).

Both cases are a depressing cautionary tale of how national economic policy can devolve into a tool for delivering rents and buying votes. They’re yet another example of why we should be skeptical of policies like anti-dumping duties, local content restrictions, and industrial subsidies that enrich a narrow group of producers and workers via a thicket of impenetrable regulations. Time and time and time again, we see that even well-intended policies can deteriorate over time, because the only ones who end up paying attention are those benefiting from the harmful status quo. And, even where the policies’ harms are obvious and clearly contrary to the national interest, they’re all but impossible to dislodge—so much so that government officials can slap 300-plus percent tariffs on construction materials (and bankrupt a few U.S. businesses in the industry) and openly ask the Biden administration to raise taxes on fruits and vegetables, with little fear that anyone in Regular America will even notice.

Except you, of course.

Charts of the Week

Please note that we at The Dispatch hold ourselves, our work, and our commenters to a higher standard than other places on the internet. We welcome comments that foster genuine debate or discussion—including comments critical of us or our work—but responses that include ad hominem attacks on fellow Dispatch members or are intended to stoke fear and anger may be moderated.

With your membership, you only have the ability to comment on The Morning Dispatch articles. Consider upgrading to join the conversation everywhere.